In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

The steady eyes of the crow and the cameras candid eye See as honestly as they know how, but they lie. W. H. Auden

We all have them: those boxes in storage, detritus left to us by our forebears. Mine were in the attic, and there were lots of them. Most were crumbling cardboard, held together by ancient twine of various types: the thick cotton kind sold for clotheslines wrapped once around and tied with an emphatic square knot; its weaker version, better suited for wrapping a packet of letters, and the shaggy blond string used for hay bales, the ends raveling.

I remember having seen some of the oldest boxes, those from my fathers and mothers families, when I was a child. They had been stored in cabinets above the piles of rags where the dogs slept in the carport and had accumulated dander and dog hair from decades of boxers and Great Danes. Though decaying with age, the boxes bore unmistakable signs of craftsmanship, such as the elegant advertisements from the era stamped on the sides, or the delicate painting on the tin case my father used to ship artworks from Pnom-Pehn in the 1930s, which gave them a decorous, dignified air.

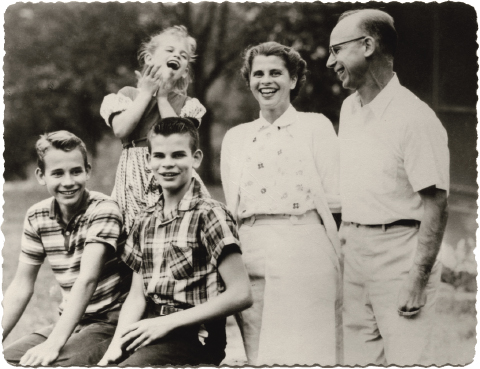

In our attic, they kept an increasingly disapproving vigil, it seemed to me, over the promiscuous sprawl of stuff that piled up around them as my husband, Larry, and I and our kids made our own histories: snapshots, of course, by the thousands, but also letters, science fair exhibits, entubed diplomas, the remains of a costume in which Jessie dressed up for Halloween as a blade of grass, snarly-haired dolls, the sawn-apart cast from Virginias broken leg when she was six, paper dolls with outfits still carefully hooked over their shoulders, report cards, spangly tutus and soiled, hem-dangling pinafores, receipts, a box of broken candy cigarettes, bank statements, exhibition reviews, a trunk of dress-up ball gowns, tatty Easter baskets still bedded with a tangle of green plastic grass, two pairs of Lolita sunglasses, their plastic brittle and faded, and the section of Sheetrock cut from the kitchen of our old house on which the heights of the children were penciled each year.

And, of course, there was also in the attic the residue of my own unexamined past: the many variously sized boxes, secured with brittle masking tape, containing letters, journals, childhood drawings, and photographs. These had been left untouched for decades as I ignored Joan Didions sage advice to remain on nodding terms, at least, with the people we used to be, lest they show up to settle accounts at some dark 4:00 a.m. of the soul.

The tape and twine on these boxes, where my familys past sleeps, might never have been cut nor their complicated secrets revealed if I hadnt gotten a letter early in July 2008 from John Stauffer, distinguished professor of English, American Studies, and African American Studies at Harvard, asking me to deliver the Massey Lectures in the History of American Civilization. After reading the letter, I cycled through the familiar antics of disbelief: forehead slapping, eye-rolling, exaggerated scrutiny of the envelope for an error but, no. They wanted me, a photographer, to deliver the three scholarly lectures at Harvard beginning on my sixtieth birthday, three years down the road, in May 2011.

Rushing to my Day-Timer, I searched in vain for a conflict. In fact, I searched in vain for a calendar page that far in the future.

No way could I reasonably decline. Years earlier, my brilliant young friend Niall MacKenzie had been given to prefacing his ironically self-inflating forecasts with the line Well, Sally, when they ask me to deliver the Massey Lectures I had heard this refrain so many times that the Masseys had come to represent for me the pinnacle of intellectual achievement. But I didnt think of myself as much of an intellectual, and I was certainly no academic. I wasnt even a writer. And what did I have to write about, even supposing I could?

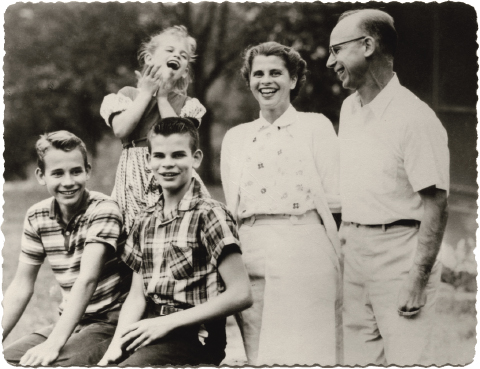

I had acquired some acclaim and notoriety, as well as the irritating label controversial, in the early 1990s with the publication of my third book of photographs, Immediate Family . In it were pictures I had made of my children, Emmett, Jessie, and Virginia, going about their lives, sometimes without clothing, on our farm tucked into the Virginia hills. Out of a conviction that my lens should remain open to the full scope of their childhood, and with willing, creative participation from everyone involved, I photographed their triumphs, confusion, harmony, and isolation, as well as the hardships that tend to befall childrenbruises, vomit, bloody noses, wet bedsall of it. In a case of cosmically bad timing, the release of Immediate Family coincided with a moral panic about the depiction of childrens bodies and a heated debate about government funding of the arts. (I had received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities but not for the pictures of my children.) Much confusion, distraction, internal struggle, and, ultimately, fuel for new work emerged from this embattled period.

Would the Massey committee at Harvard expect me to justify my family pictures all these years later? I didnt mind doing that, but I hoped I could also focus on the work that came afterward, deeply personal explorations of the landscape of the American South, the nature of mortality (and the mortality of nature), intimate depictions of my husband, and the indelible marks that slavery left on the world surrounding me. With trepidation, I called John Stauffer, and his answer only made me more anxious: anything, speak about anything you want.

Oppressed by this indulgence and uncertain how to proceed, I went into a spasm of self-doubt and fear so incapacitating that it was nearly a year before I told Stauffer Id do it. And then, as often happens to me, the self-doubt that had dammed up so much behind its seemingly impermeable wall allowed the first trickles of hope and optimism to seep out, and through the widening crack possibility flooded forth. Insecurity, for an artist, can ultimately be a gift, albeit an excruciating one.

I began looking for what I had to say where I usually find it: in what William Carlos Williams called the local. I wonder if he would think my admittedly extreme interpretationworking at home, seldom leaving the spacious plenty of our farmtoo much local. For Larry, it sometimes is: he once irritatedly clocked five weeks during which I didnt so much as go to the grocery store. But like a high-strung racehorse who needs extra weight in her saddle pad, I like a handicap and relish the aesthetic challenge posed by the limitations of the ordinary. Conversely, I get a little panicked when I have before me what the comic-strip character Pogo once referred to as insurmountable opportunities. It is easier for me to take ten good pictures in an airplane bathroom than in the gardens at Versailles.

Next page