THE BOY KINGS

OF TEXAS

THE BOY KINGS

OF TEXAS

A MEMOIR

DOMINGO MARTINEZ

LYONS PRESS

Guilford, Connecticut

An imprint of Globe Pequot Press

Copyright 2012 by Domingo Martinez

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Text design: Sheryl Kober

Project editor: Kristen Mellitt

Layout artist: Justin Marciano

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN 978-0-7627-7919-2

Printed in the United States of America

E-ISBN 978-0-7627-8681-7

For Velva Jean

and because of Sarah

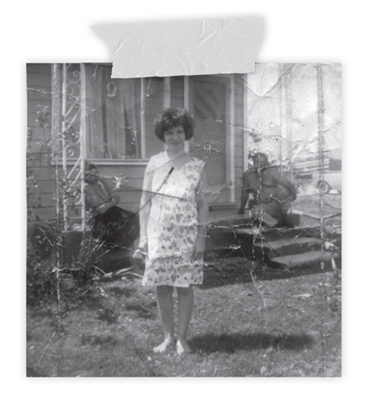

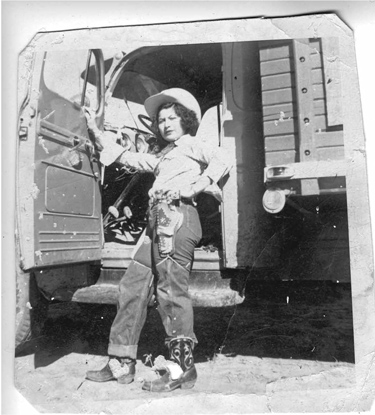

Gramma in Matamaros, late 1950s

Contents

Prologue

It began as a joke, when I was in my late twenties.

I thought Id make my older brother Dan laugh by learning a song in the long-forgotten Spanish from our youth, then belt it out unexpectedly some afternoon when we were having beers.

The song was by Vicente Fernandez and was an unofficial anthem for the Mexican farming class, back when Dan and I were growing up on the border of Texas and Mexico in the 1970s and 1980s. When it came on the radio, it would make anyone listening stop what they were doing and sing along at top volume with Mr. Fernandez in pure, animal joy, like an overemotional call to arms.

The song was, or is, rather, El Re y , (The King), and was originally written by Jos Alfredo Jimnez, a near-illiterate troubadour who wrote over one thousand songs, it is reported, even though he never learned to play an instrument.

The song was so popular on the border that even my grandmother, who was not known for her joie de vivre , would bounce along happily in a mock waltz and sing out as the spirit overtook her, in uncharacteristic glee:

Con dnero, o sn dnero... (If Im rich, or if Im poor... )

One afternoon, after blaring the song repeatedly on my stereo in order to retrace those disused paths of languagemuch to the confusion of my neighbors in Seattle, Im sureI made one of the most startling discoveries of my early adulthood.

Vicente Fernandez, I was told by my friend, David Saldana, who grew up in the Chicano movement of 1960s California, was sort of a farmers Frank Sinatra, and sang the rancheros and corrdos traditional to that class. (David, who grew up in urban areas, was more partial to Juan Gabriel, who was considered posh.)

What I could not have known growing up and hearing Vicente Fernandez all around me in South Texas was that he was singing the paean of machismo, the topographical map of the rural Mexican males emotional processing.

Right in front me, after a quick online search, was the lyrical genome for machismo. Jos Alfredo Jimnez had mapped the emotional DNA of the border male, had illustrated clearly what had so viciously plagued my father, and, well, his mother, who was as butch as they come.

Here was the source code for everything I was trying to escape: the generational compulsions and impulses of alienation, narcissism, self-destruction, emotional blackmail, and a profound conviction that everyone else in the world is wrong wrong! wrapped in a deep, all-consuming appeal to be accepted, protected by an ever-ready defensive, fighting posture, perfectly captured in a song. I was stunned at the accuracy; Jimnez, in his illiteracy, was nothing short of brilliant.

This is the song, and my bad rendering to the right:

El Rey

Yo s bien que estoy afuera

pero el dia en que yo me muera

s que tendras que llorar

Llorar y llorar

llorar y llorar

Diras que no me quisiste

pero vas a estar muy triste

y asi te vas a quedar

Con dinero y sin dinero

hago siempre lo que quiero

y mi palabra es la ley

no tengo trono ni reina

ni nadie que me comprenda

pero sigo siendo el rey

Una piedra del camino

me ense que mi destino

era rodar y rodar

Rodar y rodar

rodar y rodar

Despus me dijo un arriero

que no hay que llegar primero

pero hay que saber llegar

Con dinero y sin dinero

hago siempre lo que quiero

y mi palabra es la ley

no tengo trono ni reina

ni nadie que me comprenda

pero sigo siendo el rey

The King

I know very well that Im on the outside

but on the day I die

I know that youll have to cry

to cry and to cry

to cry and to cry

You say you never loved me

but youre going to be really sad

and thats how I demand you stay

If Im rich or if Im poor

I will always get my way

and my word is law

I have neither a throne nor a queen

nor anyone that understands me

but I will keep on being the king

A stone in the journey

taught me that my destiny

was to roll and roll

to roll and to roll

to roll and to roll

Then a mule-driver once told me

that you dont have to be the first

to arrive,

but you have to know how to arrive

If Im rich or if Im poor

I will always get my way

and my word is law

Im without throne or a queen

nor anyone that understands me

but I will keep on being the king

It loses quite a bit in the translation, but dear God, this is really what they felt. This was truth, and it was the water Dan and I swam in, growing up.

We were the sons of kings.

Music and lyrics by Jos Alfredo Jimnez; translation by Domingo Martinez.

Chapter 1

Border Justice

They were children themselves, my mother and father, when they started having children in 1967 on the border of South Texas. Dad had just graduated from high school and in a panic asked my mother to marry him because he wanted to avoid the Vietnam War draft. Mom had eagerly agreed, in order to escape something even worse.

They had three girls in three successive summers, and were then happily surprised by a boy the following year. Having done her duty in producing a son for her husband, Mom was allowed some ten months off from incubating yet another child. Or maybe Dad had finally discovered condoms. Perhaps theyd bought a television. Whatever the reason, there was a full eighteen months before I was born, the fifth child and a second son, at least for a while.

Most of the kids had been born in August or September, roughly nine months after Thanksgiving, when the Dallas Cowboys traditionally played. Dad had been a Cowboys fan since their inception, and their winning streak in the late 1960s coincided with the conception of most of his children. The year I was next to be born, the Cowboys didnt win, so I was conceived sometime during grain season, when he was maybe flush with cash and had come home drunk, which is possibly the reason I hate sports and am very fond of bread.

Collectively, we have vague and dreamlike memories from those early days of the burgeoning family, but one stands out for all of us. In it, Dad surprises us one afternoon by bringing home the smallest puppy we had ever seen. We stand around him and watch him feeding it with a bottle, and after a while he cups it in the palms of his hands and offers it to one of my sisters while the rest of us watched this and cooed enviously: There was no way she was going to keep this dog to herself, we had all subconsciously decided.

Next page