The Art of Checkmate

new translation by Jimmy Adams

Georges Renaud and Victor Kahn

Contents

Translators Foreword

The Art of Checkmate has been a best selling chess book, praised for its instructional value, ever since it was first published in Monaco in 1947.

However, when the first French to English translation appeared in the 1950s it was severely criticised by the highly respected chess writer and teacher, Cecil Purdy, who wrote in the Australian magazine Chess World:

The Art of Checkmate by Georges Renaud. and Victor Kahn, former champions of France, is yet another demonstration of how very suited the French literary tradition is to chess exposition. The close attention to the order and neatness of presentation makes study of most of the French chess writers a pleasure. In this case, a clumsy translation has succeeded in making merely delightful what could have been made super-delightful. It is a magnificent exposition of that vital department of chess skill, the mating combination.

The original was LArt de Faire Mat, of which my copy I dont know if a nicer edition was printed is on poor paper and very unattractive to the eye. Bells have produced an English edition in their usual style well-nigh impossible to better as far as the appearance goes.

The excellence of the presentation is still there, too the order, the neatness, and the pleasing system of classification according to names, which makes everything so easily remembered, e.g., Lgals Pseudo-Sacrifice, Grecos Mate, Anastasias Mate, Bodens Mate, Blackburnes Mate, Anderssens Mate, Pillsburys Mate, Damianos Mate, Morphys Mate, the Arabian Mate, and so on. All these mates the student discovers are typical mates that occur daily. They are not ephemeral flights of genius recalled only in print, but part of the stock in trade of every expert player; but a book like this that codifies them so elegantly and interestingly gives even an expert a far better grip of them, so that his chances of scoring a vital extra point in a tournament are appreciably increased. Over and over again, the authors quote instances of forced mates missed by masters in the heat of battle. And for the average player, from now on we list this as a must book.

I am strongly opposed to the view that skill in chess can be attained only by hard work. I once studied a book on the differential calculus that was written quite flippantly, and yet gave a newcomer to the calculus a much better idea of its mysteries than the ponderous school texts I was supposed to be using. A chess book that is interesting and entertaining and yet has the subject all sewn up thats the ideal, and Renaud and Kahn have hit the jackpot.

They could, however, institute a lawsuit against the translator. I really must comment on this aspect in the hope that chess publishers may exercise more care in the selection of people for this work. Previously, I railed at some faults in translations of books by Botvinnik faults that were obvious without knowing Russian. But the translation of Renauds and Kahns work reaches what I sincerely hope is an all-time low. I am no French scholar, but any fourth-former could fault this stuff.

In almost every page one finds sentences that are not translations at all, or even paraphrases. They contain as much of the original as the pathetic skull of Yorick contained of the soul of that lively jester, and the bones are padded out not with the thoughts of Renaud and Kahn but, rather, thoughts of the translators own which he seems for no valid reason to prefer ...

Cecil Purdy then goes on to give illustrative examples to support his criticisms.

Thus it is to rectify these serious shortcomings and do full justice to the original work of Georges Renaud and Victor Kahn, that we have endeavoured to produce a fresh and accurate translation of LArt de Faire Mat, whilst at the same time converting the old descriptive notation used in the English version to modern figurine algebraic and making various analytical observations, which are given in italic type.

We hope this new edition of a timeless classic will continue to benefit and be enjoyed by players of all strengths for many more years to come.

Introduction

Nothing is more annoying for a player, after he has racked his brains over a position and then selected and made what he thought to be the best move, than to hear a voice in the gallery exclaim in an ironic tone:

Everyone to their own taste but in your place I would have preferred to announce mate in two moves.

And he is astonished to discover that there really was a mate in two moves and that his premature exchange of pieces has destroyed the opportunity for ever. He curses himself for not having seen it.

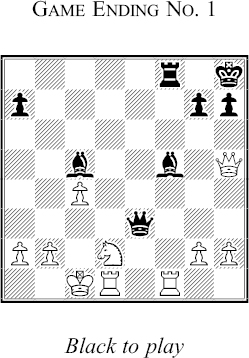

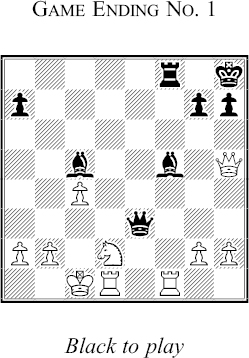

Here is a typical example. In the diagram position it was Black to move in a club tournament. The player of the Black pieces thought for a short moment, then he picked up his Queen, held it for a moment in the air and placed it triumphantly on d3. Indeed, he threatened c2 mate.

White sacrificed the exchange by xf5 and having two pawns more, exchanged Queens a few moves later and easily won the game.

When it was all over, the loser said:

There was nothing I could do. I had sacrificed two pawns and the exchange for an attack that didnt come off.

Replacing the pieces in the diagram position, we showed him that there was a forced mate in two moves. The player thought for a few minutes and finally exclaimed:

Well, I never ...

At last, albeit a little late, he saw the mate:

1 ... c3+! 2 bxc3 a3 mate.

However this is a classic mate which, ever since the distant day in 1857 that Boden played it for the first time, has been reproduced a considerable number of times. Perhaps the same player had seen it in a chess book or magazine. But as no one had drawn his attention to the mechanism of this mate, the position was as new to him.

The first thing the student must do is to learn how to spot the mates. One will never be a good player if one cannot detect these mates and if one does not know how to carry them out.

If an amateur, with some practical experience, is shown a position and told: There is a mate in five moves, find it!, he will discover it more or less easily, perhaps after a period of reflection but he will always discover it.

But let this amateur encounter the same position in a game and eighty per cent of the time, if not more, he will be blind to the mate.

Even very great masters have not escaped such misfortunes. Here are two examples that are particularly instructive:

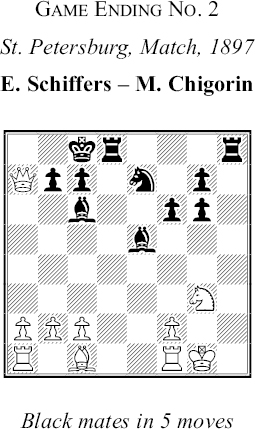

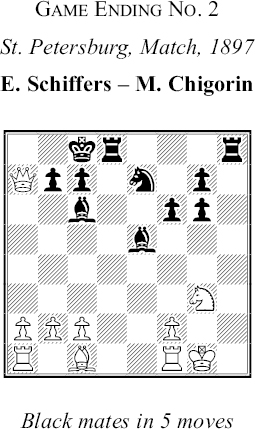

Chigorin, in a match against Schiffers, played in Russia in 1897, reached the following position with Black:

He played ... b6 and the game was drawn, whereas he could have announced mate in five moves.

| ... | h1+! |

| xh1 | h2+! |

| xh2 | h8+ |

| g3 | f5+ |

| any | h4 mate. |

At the tournament in Hastings in 1937/1938, the winner S. Reshevsky, having the Black pieces against W. Fairhurst, thought a long while in the position shown in the diagram and finally played 1 ... h6? However, he could have carried out a classic mate: