Contents

Landmarks

Page List

CONTENTS

Introduction

Ive never been to the Arctic. I have no memory of seeing a polar bear. But a polar bear is, and always will be, my favorite animal. I grew up with two dogs, three cats, a rabbit, a duck, a lamb, four birds, and an unknown number of goldfish, and, right now, there is a dachshund named Basil snoozing on my lap. How would all these animals feel if they knew that my favorite animal is one I have never encountered? I would, in my defense, try to explain to them that my fondness was not based on polar bears being living, breathing animals. I would say that it was like a celebrity crush, a superficial relationship based entirely on the idea, or image, of the animal, a somewhat delusional imagepolar bears as lovers of ice cream and soft drinks, as friendly, cuddly giants with a lumbering gait and fur as pristinely white as the frozen world they inhabit. I would go on to reassure my council of pets that I cant say with certainty if it mattered to me as a boy that polar bears actually existed. That I cant say with certainty how I would feel, as an adult, if they became extinct. As an animal lover, I would be sad, of course, but is it possible to grieve an animal that is, for me, imaginary? What will I have lost if the polar bear is lost? After all, the bears image will live on, and it was their image that captivated me in the first place.

The state of mental and physical separation between humans and animals has largely been blamed on the Industrial Revolution and the growth of cities, but the all-consuming rise of image culture has also played its part. Animals both familiar and exotic exist to us now mainly as cartoons, brand figureheads, and wholesome illustrations on food packaging, and when many of us do encounter animals that were once part of daily lifecows, pigs, sheep, and goatsthey are reduced to spectacles that require a ticket to touch. Though we remain close to our pets, they are often used as social media stooges, or dressed up and personified through memes. We pamper pets like peopleof course we doand assume that what makes us happy (regular baths, clean sheets, and filtered water) makes them happy, too. And, to some extent, it obviously does. But Ive met truffle dogs that live outside, in cages covered with their own piss and shit, that seem equally high on lifeperhaps even more so, because maybe, just maybe, that standard of domestication remains respectful to what the dogs are. In short, they are animalsanimals that derive a great deal of pleasure from sticking their noses in places that humans dont.

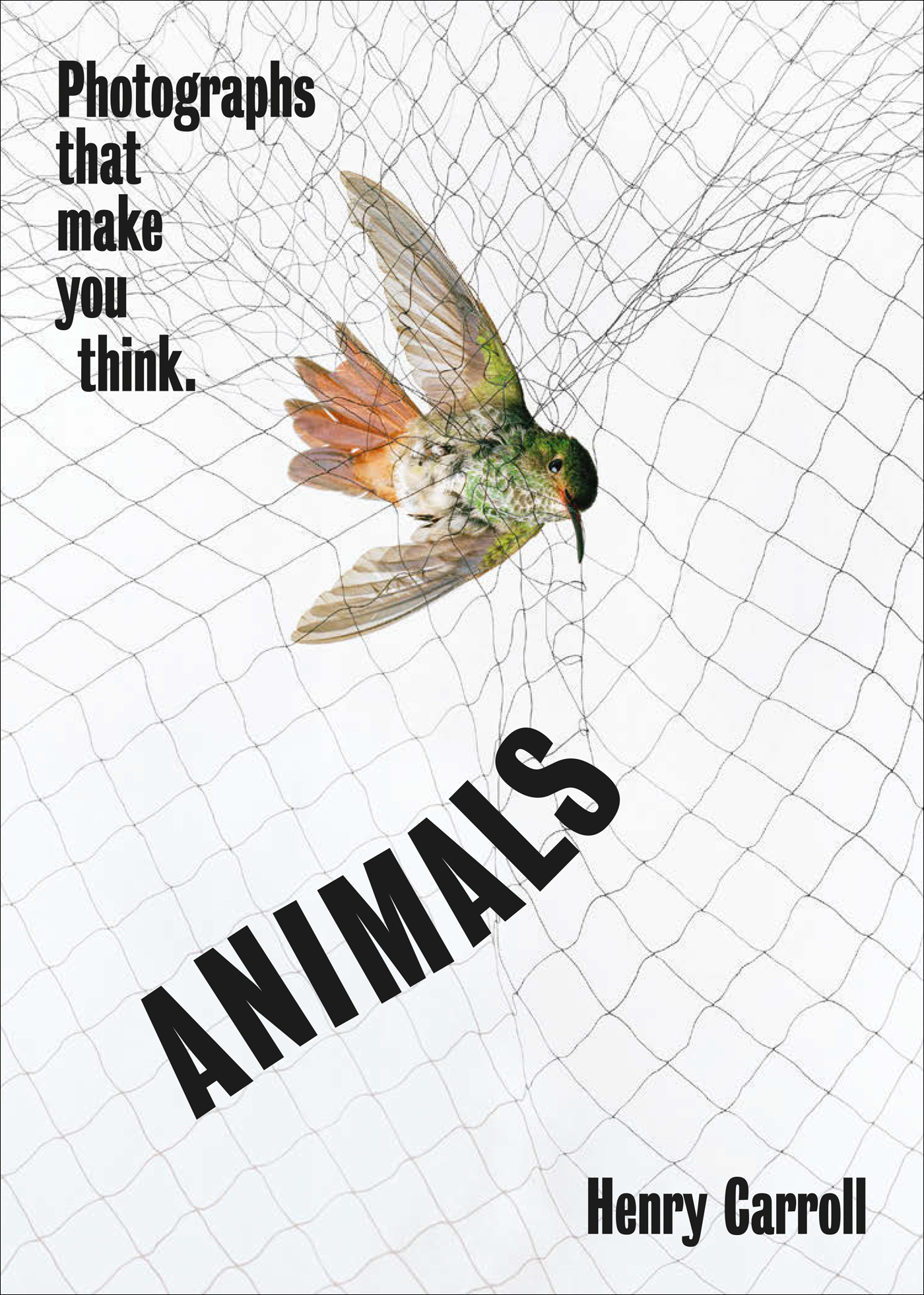

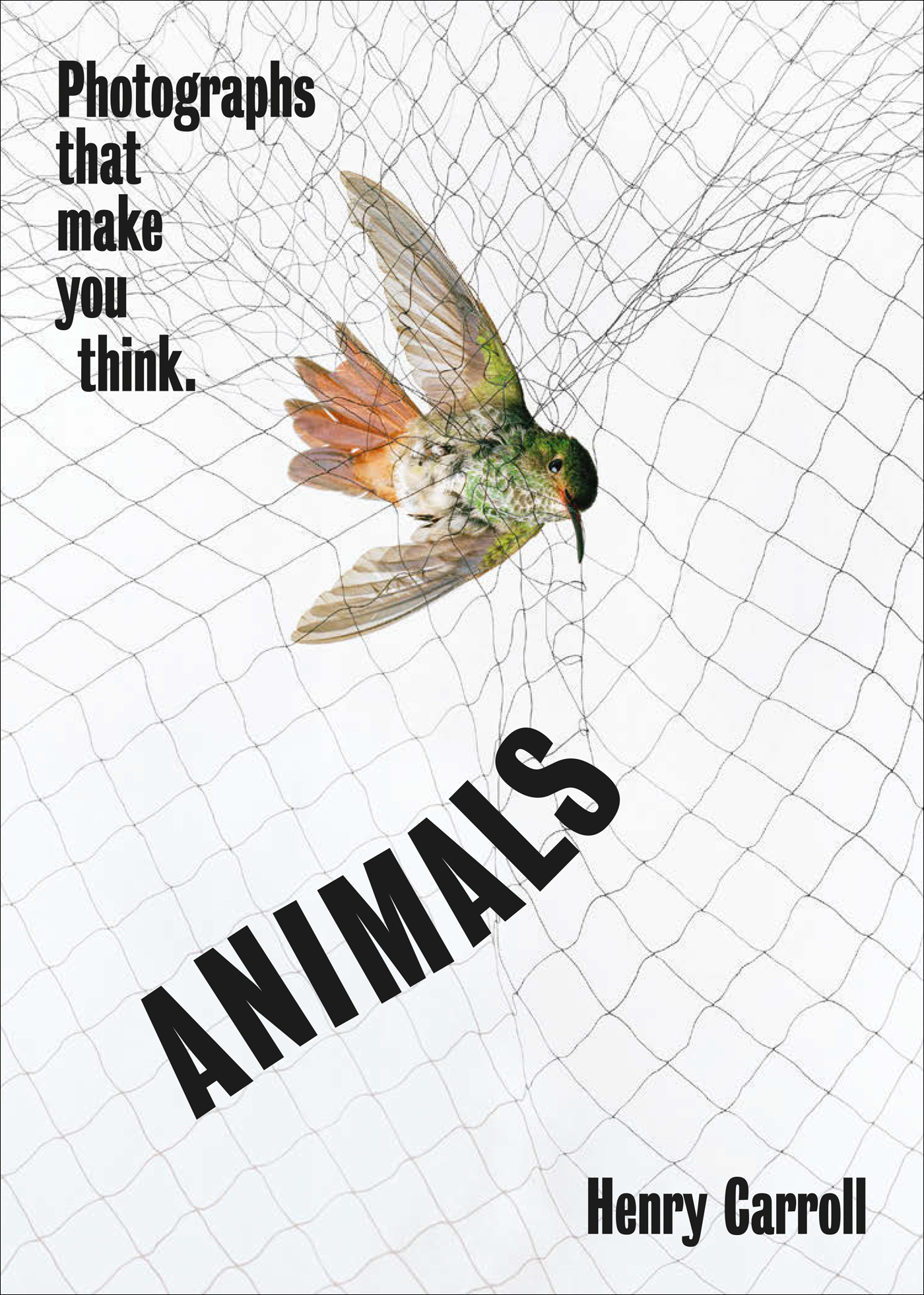

And then there is wildlife photography. In this arena of still and moving images, animals have become a dazzling means to illustrate the marvels of the medium. The captions in wildlife photography exhibitions routinely feature more information about shutter speeds, f-stops, and focal lengths than information about animals, and nature programs come with behind-the-scenes bonus episodes where the people take center stage, as if that is where our fascination really lies. And though it is no mean feat to freeze the frenzied flaps of a hummingbirds wings or focus on the whites of a tigers eyes at a thousand yards, wildlife photography only ever offers a very superficial view of animals. It does, in many ways, the opposite of what it intends. Rather than strengthen our bond, it aestheticizes animals, reduces them to decoration or entertainment, thereby emotionally distancing us from themthe real them.

Consider, for instance, David Attenborough. When Attenborough joined Instagram in 2020, he reached one million followers faster than anyone else ever had. After just four hours and forty-four minutes, he had smashed Jennifer Anistons previous record of five hours and sixteen minutes. One can only assume that it wasnt the ninety-four-year-olds bonhomie that attracted so many followers, but rather their appetite for the images of exotic animals that Attenborough was sure to post. This is not to deny Attenboroughs achievements: He has done more than any other living person to raise awareness of the natural world. Its just that he knows, as do his camera crews, that modern audiences will engage with the plight of the critically endangered Isthmohyla rivularis tree frog only if it is made hyperrealif its portrayed as a glossier, more saturated, and charismatic version of itself. Otherwise, it is just a frog. And you cant cuddle a frog.

We tend to view animals not as they are but as what we want them to be.

So where does this leave us? Given that our main source of information about the natural world also contributes to our separation from it, how can we rediscover a meaningful, authentic relationship with the animal kingdom at such a critical time, when it is not just the survival of other species at stake, but our own?

Here is a collection of photographers who dive into the depths of their own observations, experiences, and psychology to raise intriguing questions about how we relate to animals in the Anthropocene. Drawing on the nuances of visual language to provoke meaningful thought, they challenge preconceptions and call established conventions to account. Tim Hawkinsons collage of an octopus, for example, offers a new and honest way of thinking about the physicality of animals and our resulting prejudices; Elena Helfrechts surreal visualizations of childhood memories and Yorgos Yatromanolakiss nocturnes of a Greek island probe the significance of animals both personal and cosmic. Irene Fenaras algorithmically induced tapestries of image fragments offer an alternative view of consumption; Ed Panars surveillance network of eyes draws out the profundity of our everyday interactions with animals; and Kiluanji Kia Henda exposes the absurdity of natural-history conventions to target colonial depictions of Africa.

Some of the photographers confront the difficult topics head on, others take a more oblique approach, using humor and eccentricity to engage us with important issues that have become all too easy to overlook. Rather than reinforce the divide between humans and animals, their work brings us closer; it allows us to reflect on a complicated relationship, a relationship in which we tend to view animals not as they are but as what we want them to be. Yet even though these photographers train their lenses on animals, their real subject is always humanity. After all, we are the one species that insists on renouncing its place within the animal kingdom. It may be inevitable, then, that the ways in which we imagine, categorize, consume, and interact with animals say more about us than about them. And when we see through the eyes of these photographers, when we become absorbed in their images and ideas, we find ourselves presented with what we now have no choice but to acknowledge: that the strangest, most inexplicable creatures on the planet are not animals, but us.

Physicality

For those living off the land, which used to be all of us, the way an animal lookedits size, sturdiness, body shape, and resulting strengthgave it a function, whether to uproot trees or to pull a cart. Animals physicality led us to value and respect the power and efficiency of some and to happily eat others. Since the Industrial Revolution, machines have replaced work animals and put an end to the close relationship we formed with them over thousands of years. Perhaps that is why we have a habit of talking affectionately to cars and kicking broken lawnmowers: Deep down, we still relate to these machines as if they were animals.