Contents

Landmarks

Page List

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Here is a certainty: In your lifetime, you will witness more rapid and fundamental changes than any other humans in the history of our species. We are, of course, the lucky ones, the ones benefiting from the accumulated knowledge and labor of the one hundred billion minds and bodies who have lived and died before. But what happens now? What happens when our constant advances see us changing the world faster than we can adapt to it? Our knowledge of medicine means that our life expectancy is now significantly longer than our bodies have evolved to withstand, and in order to go the distance, we need to be pumped with drugs and have our bones, quite literally, reinforced.

Though we are only human and nobody is perfect, the acceleration of image culture has brainwashed us into accepting very specific and very narrow definitions of beauty that exclude almost everyone. At the same time, and on a weekly basis, science is providing definitive answers to questions that have preoccupied us for millennia. These answers are entirely at odds with those provided by the worlds religions, yet the vast majority of us maintain an unshakable commitment to our faith and turn to it for guidance above all else. Today we are never lost, we are never out of contact with those we love; but this newfound connectivity is starting to chip away at our primal need for physical touch, for authentic interactions with people and nature. In terms of health and wealth, inequality has spiraled out of control to such an extent that death and taxes are now starting to feel like optional extras for those at the top. In the West, many of those belonging to the group that has held on to power for so longwhite peopleare struggling to accept that in order to achieve meaningful equality, they are going to have to share all the fruits of human endeavor. And then there is the biggie: our unrelenting and excessive levels of consumptionour desire for bigger, smaller, faster, cheaperthat is now confronting us with the possibility of our extinction. Nothing, anymore, feels permanent.

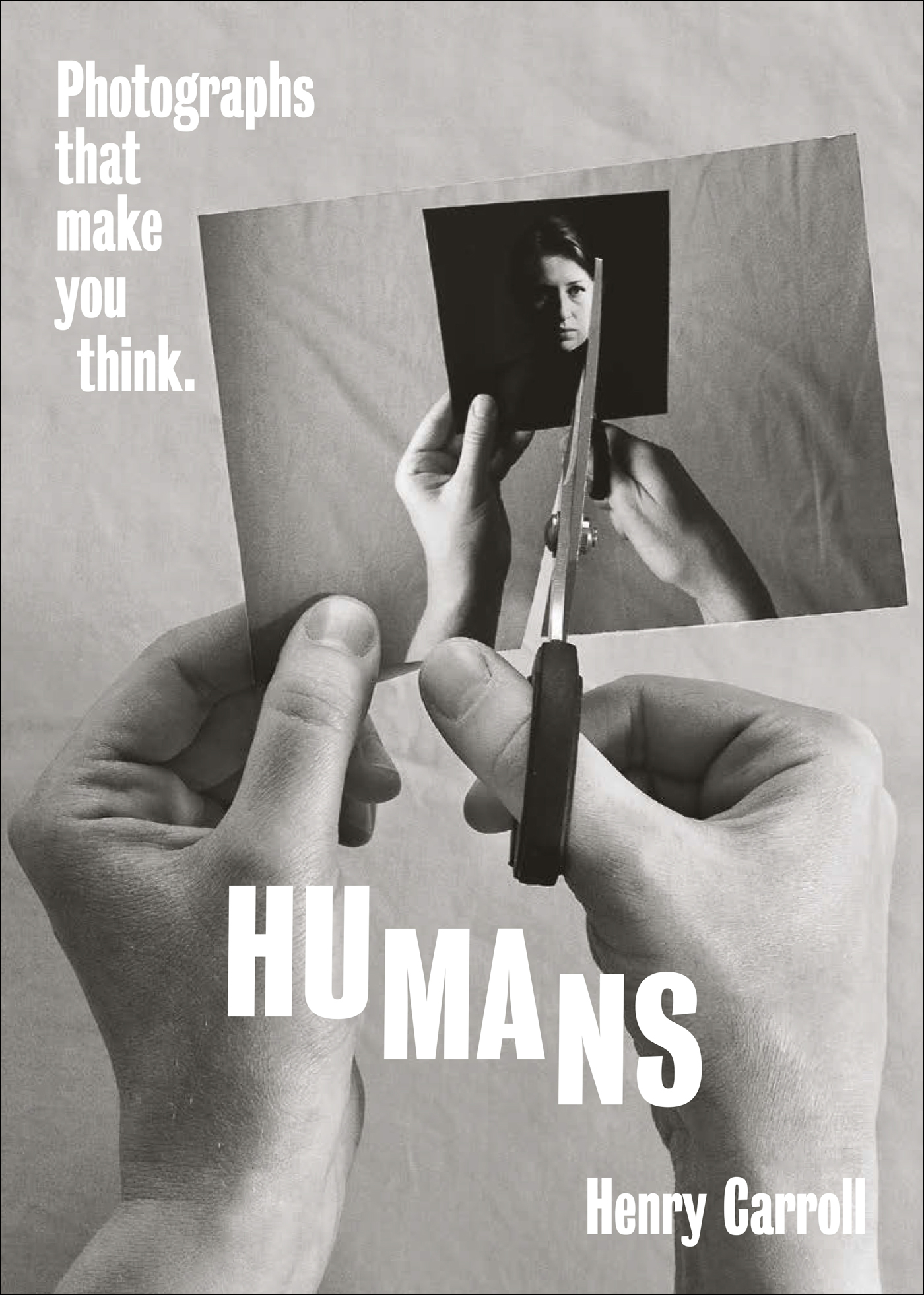

As is often the case, it takes the eyes of an outsider to see whats really going on. Unfortunately, since our own eyes are the only ones we have, we humans lack that privilege. A more advanced alien species might look at our current situation with amusement: Behold the growing pains of a fledgling civilization! they might gurgle. Or maybe not. Perhaps they, like many of us, would be a little nervous, a little dumbfounded by the paradox at the heart of it all: We humans have gone full throttle and created a world to suit our needs, and now we find ourselves struggling to adapt to the world we have created. And though we cannot turn to aliens for answers, we can at least turn to those of us who are dedicated to helping us see ourselves a little more clearlynamely, artists, and more specifically artists of the photographic kind, who quite literally have the power to freeze time to give us a much-needed pause for thought. Their work is confronting and instinctive. It is the product of very human humans who feel the urgency of this moment in time, a time when we must take a breath to ponder our place, as individuals and as a collective, in this strange new world.

For me, your fellow human, compiling a relatively concise book on such a gigantic subject was, of course, a daunting challenge. Even the word itself, humans, feels a little abstract. I am a human. You are a human. We are humans. But what does that mean? What connects me to you and us to everybody else? What, if anything, is still important to us all? Though I cannot say I have arrived at the answer, I have arrived at an answerone offered to me by the photographers featured here. Slowly, something revealed itself as I collected the work of hundreds of photographerssomething I could not ignore. Using keywords to categorize their concerns, I found that one of the following five words appeared next to almost every photographer: Body, Faith, Connection, Division, and Control. It seemed that for many photographers, these areas of interest (and contention) are the kernels at the core of their reflections on humanity; and as you immerse yourselves in the images, its my hope that youll begin to see why.

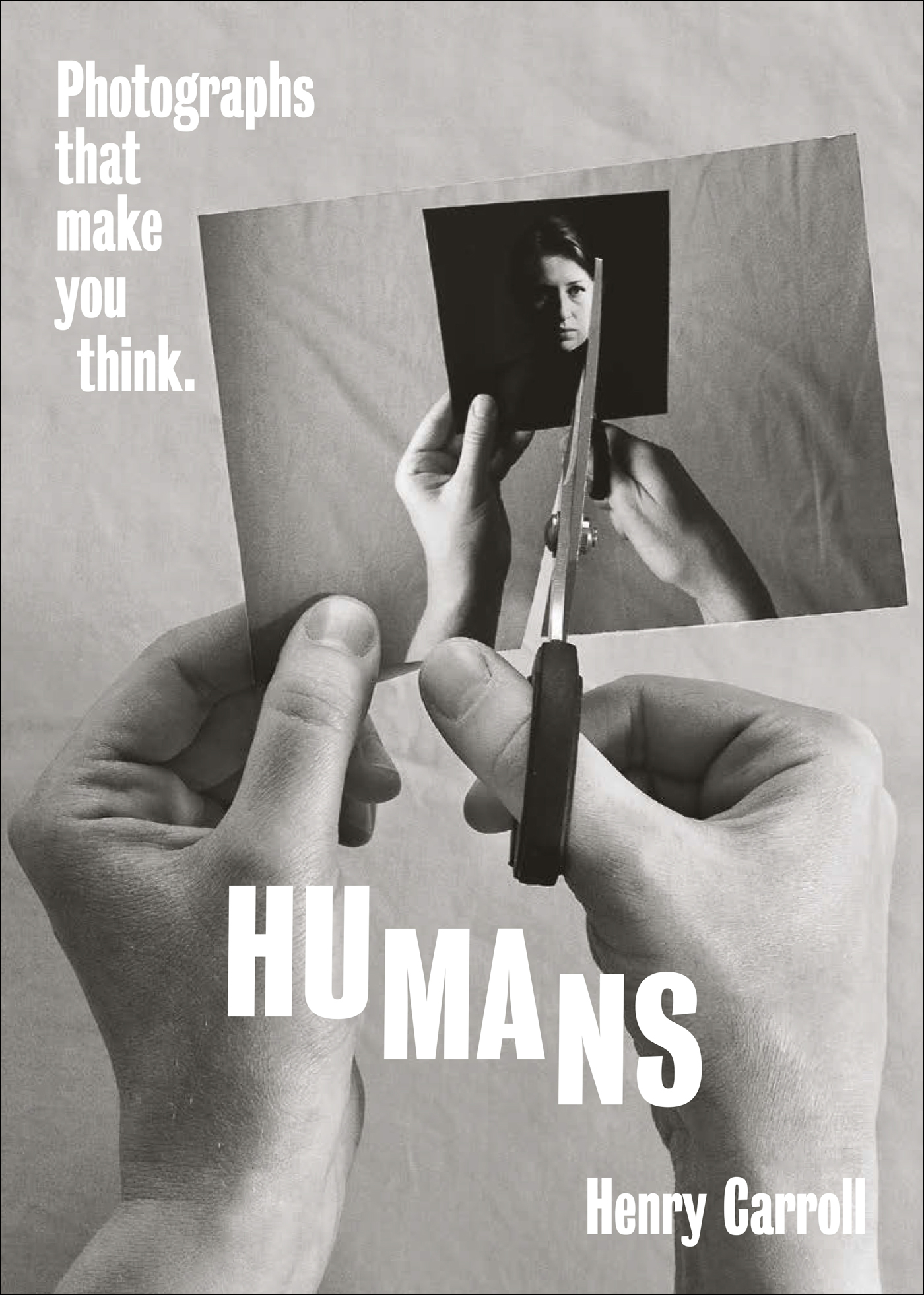

There is something very primal, something deeply human, about these aspects of our existence, which relate to our conscious awareness of our bodies, our need to believe in something greater than ourselves, our desire for intimate human contact, our innate impulse to form and protect groups of similar individuals, and our need for social order and hierarchies of power. Yet when we perceive the world around us, its clear that these aspects of being human have grown into societal norms that all too often put us in conflict with our primordial needs. In fact, for many, they have become entrenched systems of suppression, intolerance, and judgment. In the section entitled Body, Mark McKnight presents us with an almost reverential gaze at male bodies that have been excluded from the parameters of beauty, while Glenda Lissette takes back control of her social media self-image through a fascinating process of digital deformation. In Faith, David Avazzadeh reflects on the commodification of spirituality in the smartphone era, while Marwan Bassiouni shows how he quite literally finds space for his Muslim faith in the West. Connection features Jonny Briggs, who probes his relationship with his parents through cathartic collages, and Pixy Liao, who finds a willing muse in her longtime boyfriend in order to challenge gender roles in heterosexual relationships. In Division, the self-portraits of Zanele Muholi and Xaviera Simmons break down stereotypical representations of Blackness and confront us with racial injustices past and present. Finally, Control sees Clment Lambelet co-opting facial recognition software to question a computers ability to understand emotion, while Amy Elkinss correspondence with people on death row provides insight into the minds of incarcerated people.

Image making is, by nature, a little primitive, a little primal. Humans have been making images for more than forty thousand years, and in a way, not much has changed since then; whether stencils of hands on the wall of a cave or a collection of pixels contained in a camera phone, all images are visual responses to what is taking place around us and within us, fleeting and not-so-fleeting acknowledgments of what matters most. Another enduring aspect of images is their inherent ambiguity. On their own, images can tell us only so much, they suggest rather than explain; their meaning, their resonance, changes from one person to the next. That is why, when it comes to reflecting on the subject of humans, visual languagethe primal languageis so important: To make sense of what we are seeing, we must bring ourselves to images. In other words, to form an understanding of an image is to better understand ourselves. You may not share the story of some of the image makers in this bookthey might be preoccupied by themes or issues that do not concern youbut I guarantee that within each image, each idea, you will find a little something that does resonate with your own human experience. Maybe Mari Katayamas acceptance of her body will, in a small way, inspire you to accept your own. Maybe you will see yourself in one of the faces that Peter Funch photographs returning to the same spot every single day. Maybe Deanna Dikemans archive, which spans thirty years of her parents waving good-bye to her in their driveway, will prompt you to think about who it is you photograph most often, and why.