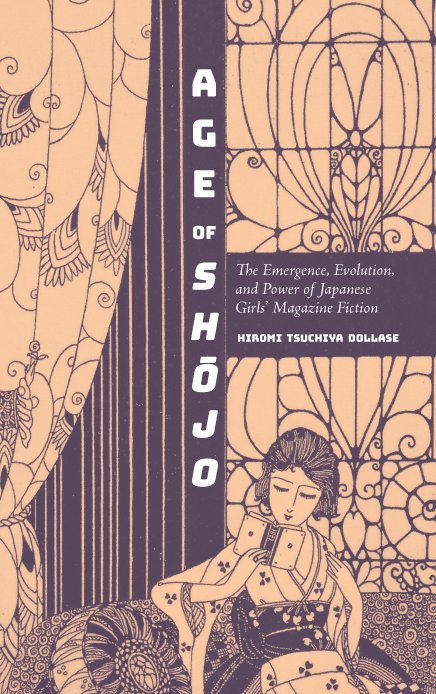

AGE OF SHJO

AGE OF SHJO

The Emergence,

Evolution, and Power

of Japanese Girls

Magazine Fiction

HIROMI TSUCHIYA DOLLASE

Cover image: Fukiya Kji, Waga Atelier. Fukiya Kji 2018.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2019 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dollase, Hiromi Tsuchiya, 1968- author.

Title: Age of Shjo : the emergence, evolution, and power of Japanese girls magazine fiction / Hiromi Tsuchiya Dollase, State University of New York.

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018021840| ISBN 9781438473918 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438473925 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Childrens periodicals, JapaneseHistory20th century. | GirlsBooks and readingJapanHistory. | Japanese literature20th centuryHistory and criticism. | Japanese literatureWomen authorsHistory and criticism. | Girls in literature.

Classification: LCC PN5407.J8 D65 2019 | DDC 895.6/0992837dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018021840

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people helped me in the years during which I produced this study. First, I would like to express my thankfulness to Eiji Sekine, Sally A. Hastings, Aparajita Sagar, and Siobhan Somerville, who served as advisers for my PhD dissertation, Mad Girls in the Attic: Louisa May Alcott, Yoshiya Nobuko and the Development of Shjo Culture (2003), from which this book project originated.

I would like to express my gratitude to Purdue University, for awarding me the Purdue Research Foundation Grant; and Vassar College, for granting me the Dean of Faculty General Fund, the Susan Turner Fund, the Salmon Fund, and the Emily Floyd Fund, all of which have enabled me to go to Japan yearly to work on my research. This book would not have materialized without the ongoing support of the Dean of Faculty Office, the Grants Office, and the Library at Vassar College.

I would like to express my appreciation to Christopher Ahn, an editor at SUNY Press, for finding my study interesting and guiding me throughout the publication process. I also owe my deepest thanks to the reviewers of the manuscript who provided extremely valuable suggestions and comments, which helped me look at the whole book with fresh eyes.

I wish to thank the journals Japanese Studies , the Journal of Popular Culture , U.S.-Japan Womens Journal , Asian Studies Review , and the Association for Japanese Literature Studies for allowing me to reproduce parts of essays that first appeared in these publications. The following publishers, museums, and individuals allowed me to use images: Mineko Miyamoto, Mitsuko Yasuda, Himawariya, Hakubunkan Shinsha, and Shinchsha, Sheisha. I would like to thank Yichi Iwano of Jitsugy no Nihonsha, and Shizuo Hasegawa of the Fukiya Kji Memorial Museum for helping me in the process of obtaining permissons. I appreciate the generosity of Tatsuo Fukiya for permitting me to use Fukiya Kjis beautiful artwork, which perfectly represents the spirit of my book, on the front cover.

I looked at many volumes of girls magazines at the Center for International Childrens Literature in Osaka, the International Library of Childrens Literature in Ueno, the Museum of Modern Japanese Literature in Tokyo, and the National Diet Library in Tokyo; without the help of library staff, my study would not have been possible. I am also grateful for the kindness of Taiko Kat, Taeko Emoto, and the members of Kitagawa Chiyo Kenshkai in the city of Fukaya, Saitama, who shared stories about Kitagawa Chiyo with me.

I always enjoyed the fun and collaborative spirit of the scholars whom I got to know throughout the course of the project and invited me to participate in workshops, conference meetings, and collaborative projects, including Tomoko Aoyama, Jan Bardsley, Nathen Clerici, Catherine Driscoll, Nahoko Fukushima, Barbara Hartley, Rachael Hutchinson, Laura Miller, Amanda Seaman, C. J. Suzuki, Masami Toku, and Patricia Welch. I also thank Kiyomi Eguro, Helen Kilpatrick, Yuko Matsumoto, and Kayo Takeuchi for sharing their girl study research. I would like to express my very special gratefulness to the late Satoko Kan, an extraordinary educator, researcher, and critic, for the friendship and inspiration she provided me. My appreciation also goes to my colleagues in the Chinese and Japanese Department and the Asian Studies Program at Vassar College, in particular, Peipei Qiu, and my research assistants, Sabrina Castillo, Jennifer Novak, Stephanie Seto, Hikari Tanaka, and Alisa Vithoontien.

This book would not have happened without the support of my family in both Japan and the United States; Susumu and Reiko Tsuchiya, Bill and Anna Mae Dollase, and my sisters, Nobuko and Natsue. Last, but absolutely not least, I would like to express my deepest appreciation to Rob Dollase who read multiple drafts of this book and helped me polish the final product. My heartfelt thanks go to him for his patience, constant encouragement, and support.

Previously Published Journal Articles

Chapter 1 was previously published as Shfujin (Little Women): Recreating Jo for the Girls of Meiji Japan, Japanese Studies 30, no. 2 (2010): 24762.

A section of chapter 3 was previously published as Early Twentieth Century Japanese Girls Magazine Stories: Examining Shjo Voice in Hanamonogatari (Flower Tales), Journal of Popular Culture 36, no. 4 (2003): 72455.

A section of chapter 4 was previously published as Yoshiya Nobukos Yaneura no nishojo: In Search of Literary Possibilities in Shjo Narratives, U.S.-Japan Womens Journal 2021 (2001): 15178.

Chapter 5 was previously published as Girls on the Home Front: An Examination of Shjo no tomo Magazine 19371945, Asian Studies Review 32 (2008): 32339.

A Note on Japanese Names

All the Japanese names from Japanese publications will follow the form in which surname comes before given name.

INTRODUCTION

Little Women , Anne of Green Gables , A Little Princess , Daddy-Long-Legs , Pollyanna , and Heidi for over one hundred years, these stories, though they originated in the West, have resonated with young female Japanese readers like no others. They have been repeatedly translated into Japanese, reprinted, adapted as animated television series and more, continuing to attract new audiences. The origin of Japanese girls fiction, shjo manga (girls comics), and even anime can be traced back to these Western stories that inspired little girls, including future fiction writers and manga artists who grew up steeped in them.

The Japanese girls fiction genre has gone through many transformations over the past century, repeatedly reshaping its themes and the images of its heroines. It has picked up and shed various attributes through the years, but at the core of todays sprawling Japanese girls culture an evolving force consisting of a pattern of attitudes and processes has persisted. Sparked by girls resistance against their oppressive fates as females in traditional Japan, this force originally manifested as a passive retreat into fantasy worlds and the attempt to maintain them beyond their practical limits. The strength of these reveries proved durable, generating attitudinal and practical changes in the lives of those they inspired. The soft power of this phenomenon, which continues to expand and advance through generations and throughout the larger culture, is a process we can identify as the way of shjo .