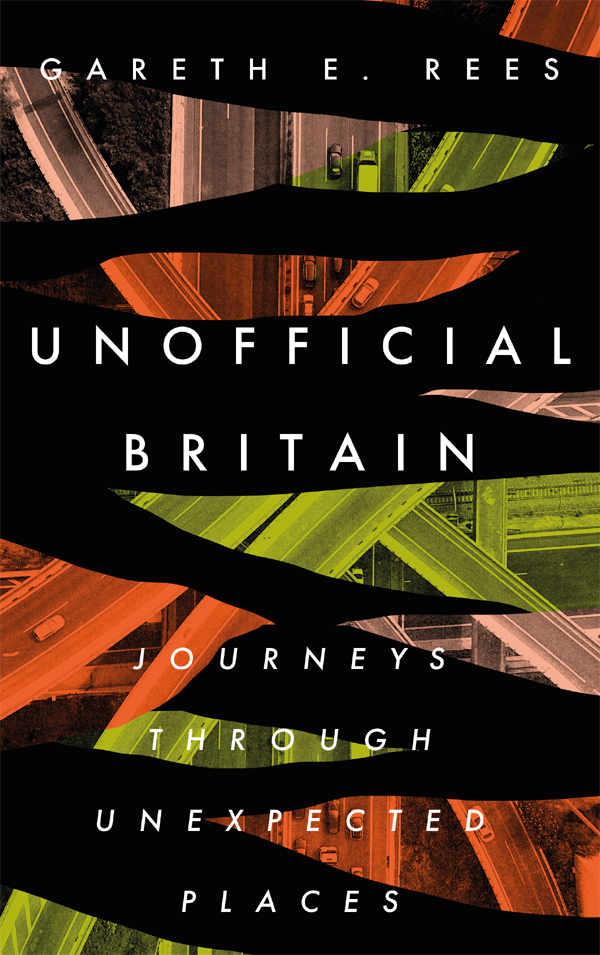

Gareth E. Rees - Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places

Here you can read online Gareth E. Rees - Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Elliott & Thompson, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places

- Author:

- Publisher:Elliott & Thompson

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To my daughters, Isis and Venus

Everything has beauty, but not everyone sees it.

CONFUCIUS

A fter a long trudge over a misty moor, you arrive at the crest of a hill and pause for breath by an oak tree. Initials have been etched into the bark by others who have stood here. Lovers. Friends. Mourners. Your eye follows a drystone wall down to the valley below, where a river meanders through a meadow; a Civil War battle took place there, one so bloody that the water ran red for a week. You smell smoke. Hear the crackle of burning wood. A crow flies out from the spire of a derelict church just visible above the trees. Bells begin to toll but you know there have been no bells in that church tower for decades. With a shiver, you descend through a holloway worn by generations of feet, hooves and cartwheels. Shafts of light glance off glistering spiderwebs. It grows cold and you dont know why. But youve heard stories about this path: the murderer who fled along it from a nearby village then vanished into thin air; the stagecoach crash that killed two lovers whose voices are sometimes heard in the wind; the knoll on which it is said a witchs house once stood, where now no flowers grow. On reaching the village, you stop outside its pub, where a mummified cat is displayed above the door and a memorial plaque tells of the man who propped up the bar each night and sang old songs until his forearms wore grooves into the wood. Streamers dangle from street lamps, remnants of May Day festivities. You stand on the cobbled street, revelling in Merrie Olde England.

This romanticised folkloric version of Britain belongs to a time before the Industrial Revolution, when the majority of people lived and worked in the countryside. We see glimpses of it when we venture down country lanes, through woods and vales, to villages with Tudor houses, Norman churches and pretty greens. It is embedded in our collective memory in the form of pastoral paintings, poetry, songs and stories. This pre-industrial age is often sentimentalised as a purer, more magical epoch of wonder and mystery, its landscape unspoiled and picturesque. Of course, if you had been alive at the time, it would simply have been the everyday; you would not have considered yourself to be living in some sublime English Eden. On the contrary, life could be brutish. Winter was tough. Homes were dirty. Work was back-breaking. Murder and rape often went undetected and unpunished. Poverty was common. There were outbreaks of disease, war and famine.

Humans have always harboured anxieties about the state of the world and the threats we face, both in this life and in whatever comes after. Before the majority could read or afford books, the primary medium for expressing these fears, ideals and superstitions was through oral storytelling. Local lore sprang from numerous, nebulous sources: rumours that grew and mutated; collective memories; political propaganda; tales told to keep children from danger; tragic events; wrongful executions; unsolved murders; explanations for natural phenomena and topographic curiosities; aftershocks of plague, war and conflict. They all originated in real events and landscapes but persisted through the ages as fiction nursery rhymes, aphorisms, myths and legends of witches, boggarts, phantom dogs that roam the hills, and ghosts of grieving widows and long-dead soldiers. These stories are expressed in dances, festivals and rituals or through totems such as Sheela-na-gigs, foliate heads and gargoyles. Theyre encoded in the names of lanes and alleys, woodlands and caves, ancient wells and stones places that have seen so many cycles of birth and death, love and grief, hope and regret that they cannot help but be deeply storied.

But wonderful though these places are, most of us today dont live in picture-postcard villages with thatched roofs, medieval inns and ancient customs, and there is a danger in fetishising that past as a halcyon world that has since been contaminated by technological progress, urbanisation and immigration. The past was not a utopia and a pure Britain has never existed in any era. The Romans, Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Danes and Normans left traces of their gods, ghosts and demons well before the end of the Middle Ages, just as African, Caribbean, Indian, Eastern European and Middle Eastern immigrants have endowed us with their traditions, music and cuisine since the days of Empire. Our culture is in constant development. The story never stops.

The industrial revolution tore up much of Merrie Olde England. People migrated in huge numbers to cities and big towns to work in factories. Mining, quarrying and new infrastructure transformed the topography. Rivers were canalised. Railways cut through the countryside, bringing noise and pollution, allowing for travel so fast it changed our concepts of time and distance. We replaced the circadian rhythms of nature with the rhythms of machinery, clocks and production deadlines. Great iron bridges spanned gorges and valleys. Ships brought cargo to bustling docklands from all parts of the Empire. Chimneys thrust into the skyline. Cities sprawled outward, consuming marshes, farms and villages. New urban landscapes presented us with new threats, new fears, new hopes, and new avenues for the imagination. Jack the Ripper and Spring Heeled Jack terrorised the smog-shrouded streets of London. Body snatchers skulked in mass cemeteries. New photographic technology captured proof of ghosts and fairies, while early electronic devices detected spirit voices in the ether. As science clashed with superstition, Victorian anxieties found expression in Jekyll and Hyde dichotomies, vampires with sexually transmitted infections, wars against superior alien technologies, and apocalyptic flood scenarios. New mythical narratives were born in this post-industrial age, which today we take for granted.

Of course, many of the traditions of rural England died during the seismic social shifts of the industrial revolution. Communities lost their generational continuity. Urban life detached people from their connection to the land, and to the seasons. Scientific enlightenment challenged superstitions and cast electric light into the shadowy corners where ghosts and demons used to hide. Many bemoaned the ugliness, pollution and overcrowding of the modern world: human beings hemmed into factories and slums, their children sick and malnourished. But as generations grew up in this environment, they knew only brick and iron, gaslit streets, steam engines and factories. This was the backdrop to their lives and loves, their dreams and nightmares. But when they died, they too left their ghosts behind, and the urban environment became as endowed with melancholy, sentimentality and nostalgia as the rural world it had superseded. Today we instinctively see beauty in an old mill, iron bridge or viaduct. It is easy to feel sentimental at the sight of chimney stacks silhouetted on a jumble of slate roofs. We dont think theres anything incongruous about an eerie tale set by a foggy canal, a defunct railway line or an abandoned mine shaft. It wouldnt surprise us at all to feel haunted inside a Victorian terraced house. These sites have a powerful resonance, saturated as they are with the many events that have occurred there. We can feel the sadness in their decay and can easily imagine the stories of their departed inhabitants.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places»

Look at similar books to Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.