Contents

Guide

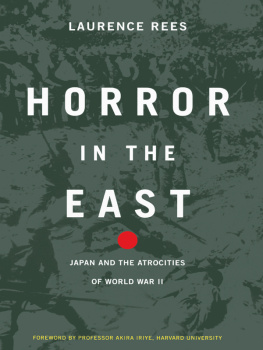

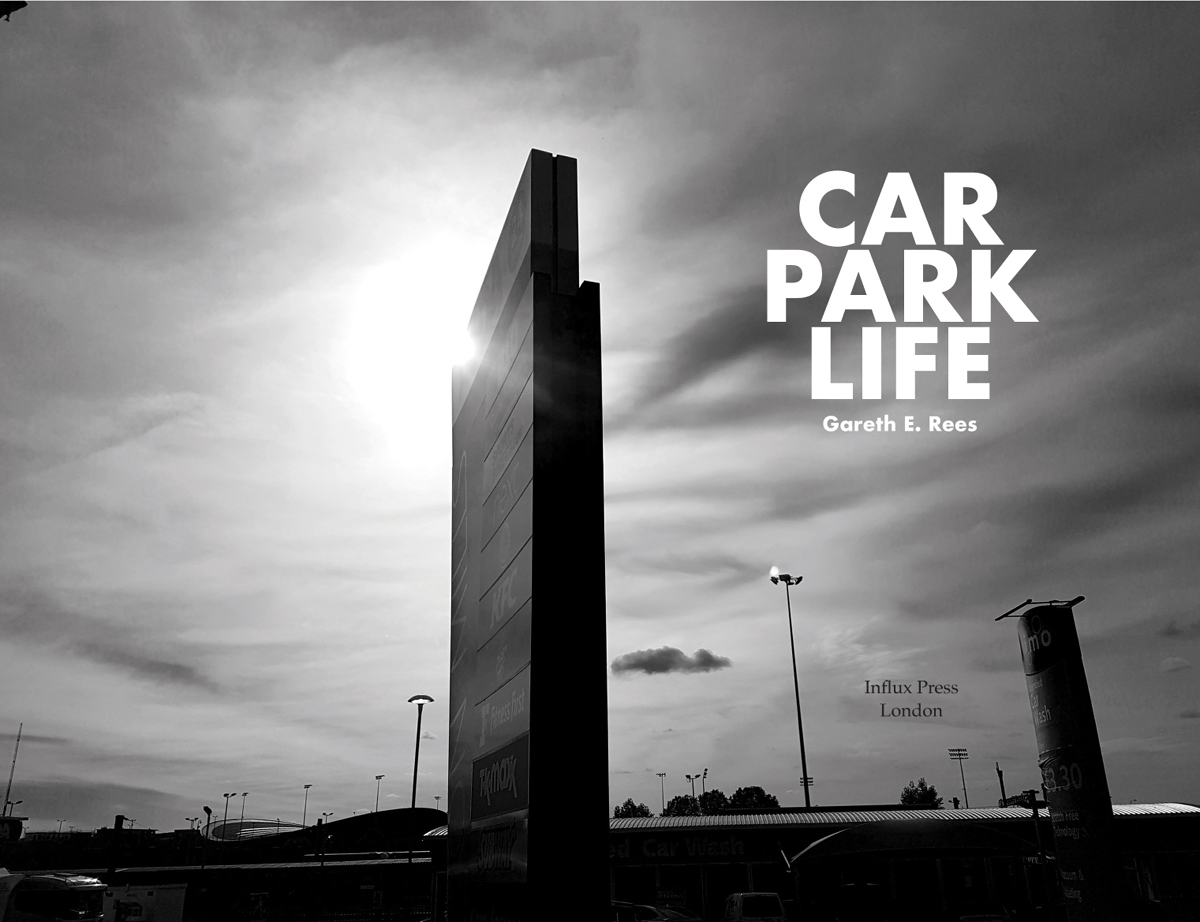

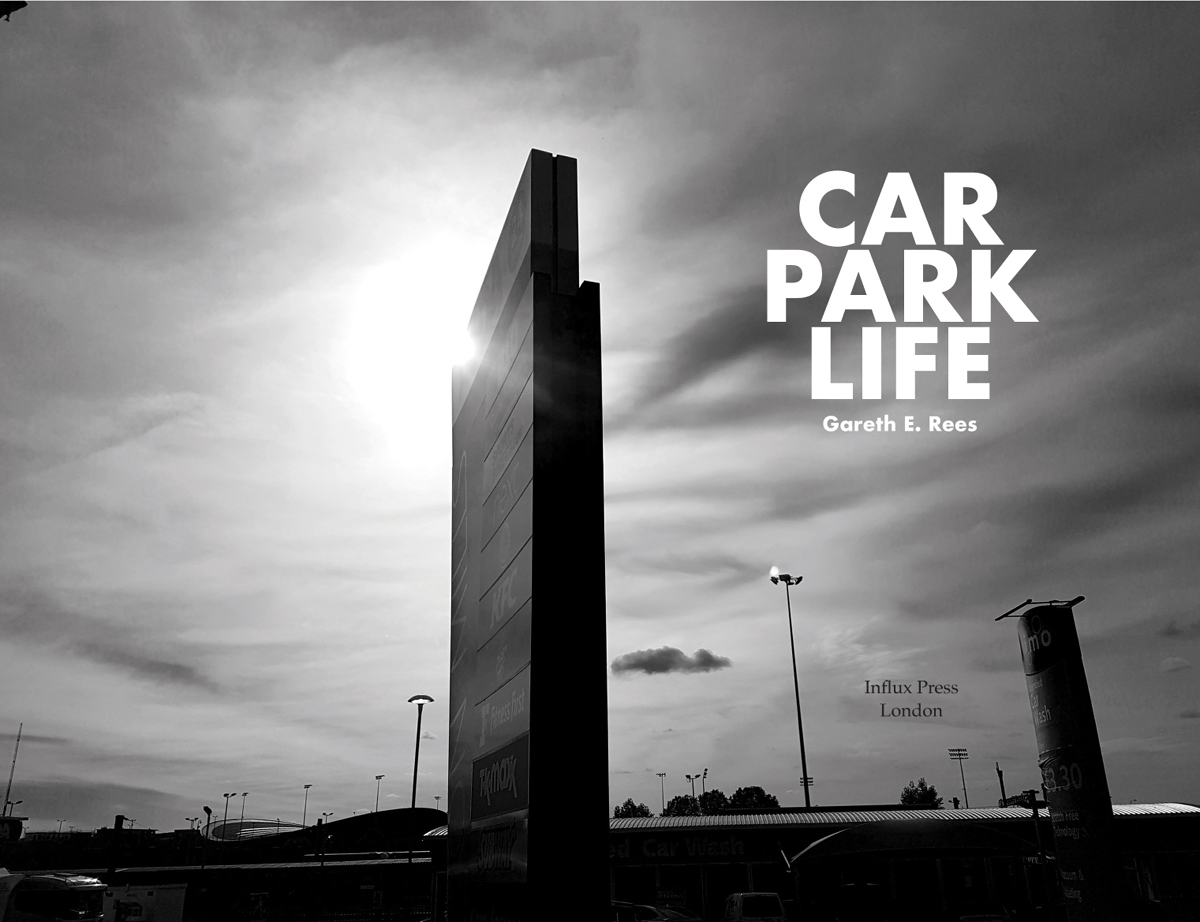

CAR PARK LIFE

Also available from

Gareth E. Rees and Influx Press:

Marshland

The Stone Tide

Published by Influx Press

The Greenhouse

49 Green Lanes, London, N16 9BU

www.influxpress.com / @InfluxPress

All rights reserved.

Gareth E. Rees, 2019

Copyright of the text rests with the author.

The right of Gareth E. Rees to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Influx Press.

First edition 2019. Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd., St Ives plc.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-910312-35-3

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-910312-36-0

Editor: Gary Budden

Copyeditor: Momus Editorial

Cover design: Austin Burke

Cover photograph: Jeff Pitcher

Interior design: Vince Haig

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

For Simon, co-pilot during the Makro years.

AUTHORS NOTE

The book is based on a series of retail car park explorations undertaken between 2015 and 2018. Some of the car parks have since been redeveloped or rebranded, but their essential spirit, or lack of it, lives on. This is by no means a comprehensive collection of British retail car parks, nor is it a complete catalogue of car park experiences. I have only scratched the surface. Everyone has a car park story and Im sure you have your own. So consider this book a primer. A catalyst. A starting point. Then go out and explore.

Part One

Entry

It is Morrisons in Hastings that lights the fire of my obsession. Not the supermarket itself but the space outside: the car park. The attraction is not instant. We dont click immediately. At first, I use Morrisons for the weekly shop, making me just like all the others who traipse between the superstore and the car, laden with bags or pushing a trolley, oblivious to the car parks charms, its mystery, its threat. After a few months, I use Morrisons not only to shop, but also as a shortcut into town. Its car park lies at the other side of an underpass at the end of my road, between a railway embankment and a Victorian street of shops and eateries at the foot of West Hill, a steep elevation behind the Norman castle. I pass through it daily on my way to ostensibly more interesting destinations: the working fishing beach, the pubs, the chippies, the bric-a-brac shops.

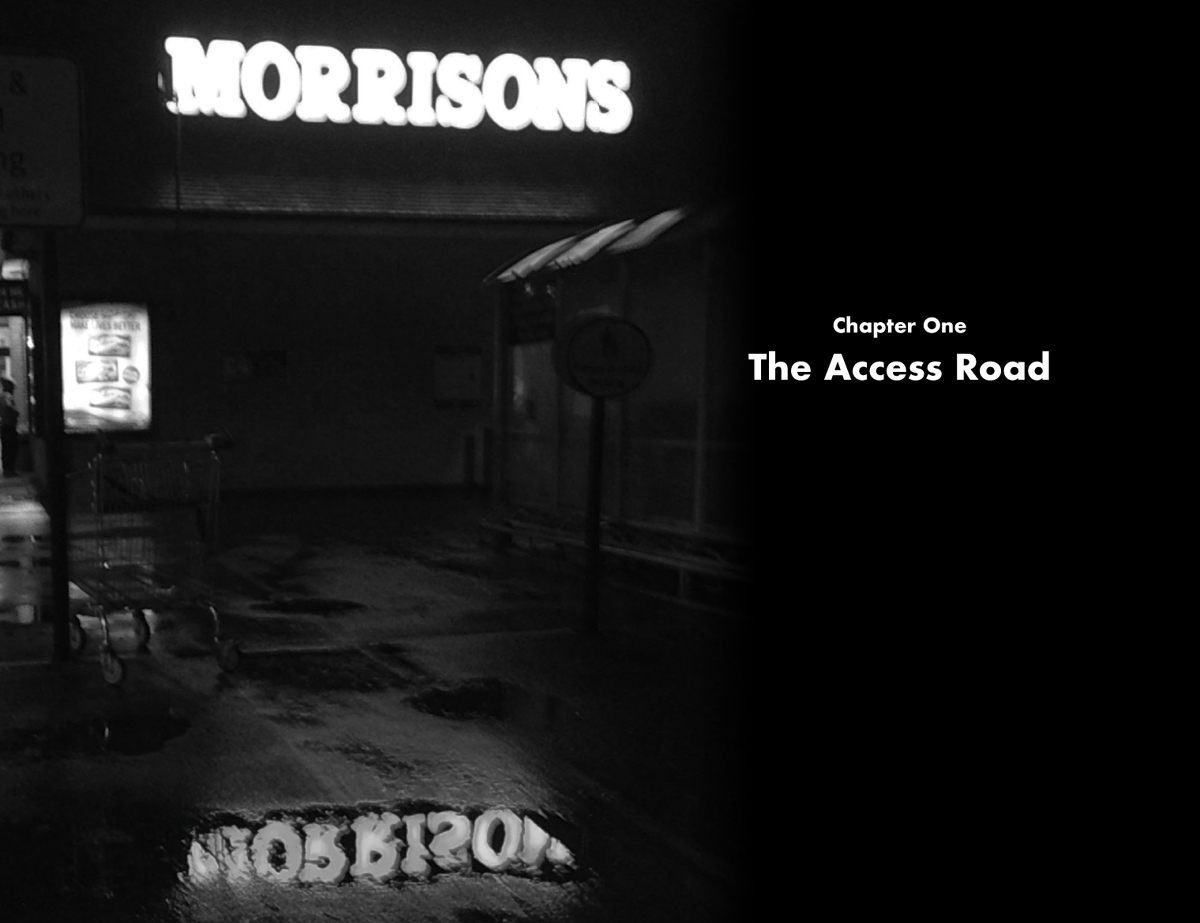

One night, I return from the pub and take my usual shortcut through the Morrisons car park. But rather than head directly to my road, I take a look around. I am in no rush and theres something alluring about the car park tonight, caught in bright moonlight after rain. Hooded lamps, crested with gull-deterring needles, shower light onto the tarmac. The yellow glow of the Morrisons sign, reflected in a puddle, has all the sad beauty of a late-night amusement arcade. I slap my foot in the water and see the stars wobble. Moondance by Van Morrison kicks off in my brain. The nights magic seems to whisper and hush as a herring gull boomerangs over the architraves and the ghost of a cleaner flits through the dimly lit interior. Vehicles are scattered here and there. A superstore car park is rarely empty, and never silent. Water trickles from the guttering. A generator hums. There is a squeak of trolley wheels and the rattle of something moving on metallic rails. A slam and bang. Bakers, perhaps, preparing the mornings batch. The disembodied voices of the night shift drift across the lots as I wander in transgressive loops, crossing white lines, disabled parking bays and the petrol forecourt, where I send a startled fox crashing into the hedge. This seems a different, wilder car park to the one in the daytime.

There are others here. By the wall, two boys with skateboards smoke joints beneath a NO SKATEBOARDING sign as a huddle of girls pass around a can of Monster energy drink. A dented sports car rumbles down the access road, driver in a baseball cap, eyes lit up like a cats in the lamp glare before he veers off into the shadowy perimeter for a reason I cannot fathom, nor dare to discover. Three lanky Polish lads by the entrance talk in low voices and shoot me a dirty look as I veer towards the recycling bins at the perimeter, where a bed frame lies in the shrubs. I pass a Mercedes with a crumpled bonnet and, disconcertingly, a licence plate that includes the number 1066. As I turn back to the supermarket I approach a car with a solitary woman inside. She fumbles with her keys in panic. I pretend to look at my phone so that she knows I have no interest in what shes up to. When I take a glance back she is twisted around in her seat, staring at me, wide-eyed. We remain connected for a torturous moment before she fires up the engine and pulls away. I get a strange sense that I have stumbled onto a drama that connects the woman in the car, the lingering Polish men, the stoned skateboarders and the crashed Mercedes; secret lives that hide in plain sight.

At the rear hedgerow of the car park I notice a sign, which reads:

THIS DEVELOPMENT IS NOT DEDICATED AS A

PUBLIC RIGHT OF WAY

ENTRY IS ONLY PERMITTED TO SHOPPERS

AND THOSE WITH THE WRITTEN PERMISSION

OF Wm MORRISON SUPERMARKETS PLC

PROCEEDINGS WILL BE TAKEN AGAINST

THOSE ENTERING ONTO THIS DEVELOPMENT

FOR ANY OTHER PURPOSE

It strikes me that I have entered the car park without any intention to shop, an illegal act in the eyes of the supermarket. The public are not permitted to walk or linger or play here. Proceedings might be taken against them. It feels like a challenge. Car parks are not only places for cars but also thoroughfares for pedestrians. Hangouts for teenagers. Theyre places to rendezvous. Bump into neighbours. Exchange goods. Get some cash out. Have an argument with your partner. Make an awkward phone call. Eat a quiet lunch away from your colleagues. Secretly munch into a diet-busting burger from that chain you tell everyone you hate. Car parks are an intrinsic part of the landscape, like them or not, and if they are going to encroach on the space where our common grounds, marketplaces, municipal buildings, factories and marshlands once were, then we have a right to interrogate the space, find a way to embrace it, even learn from it. What do we even know about these places? Are they simply slabs of tarmac or are they something more? Do they have the potential to contribute something of worth to society? Or are they pernicious entities, Trojan horses of neo-liberalism, ruining us from the inside? Sites of psychosis, decay and disaster? Someone needs to find out, and this kind of landscape is right up my street. In the same way that a rambler who walks the same route regularly through private land can convert it to a public right of way, given enough time, perhaps I can do this with retail chain store car parks, and help reclaim the space for the good of all.