This publication was supported in part by the Donald R. Ellegood

International Publications Endowment.

Copyright 2003 by the University of Washington Press

First paperback edition 2015

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Audrey S. Meyer

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

Kennan, George, 18451924.

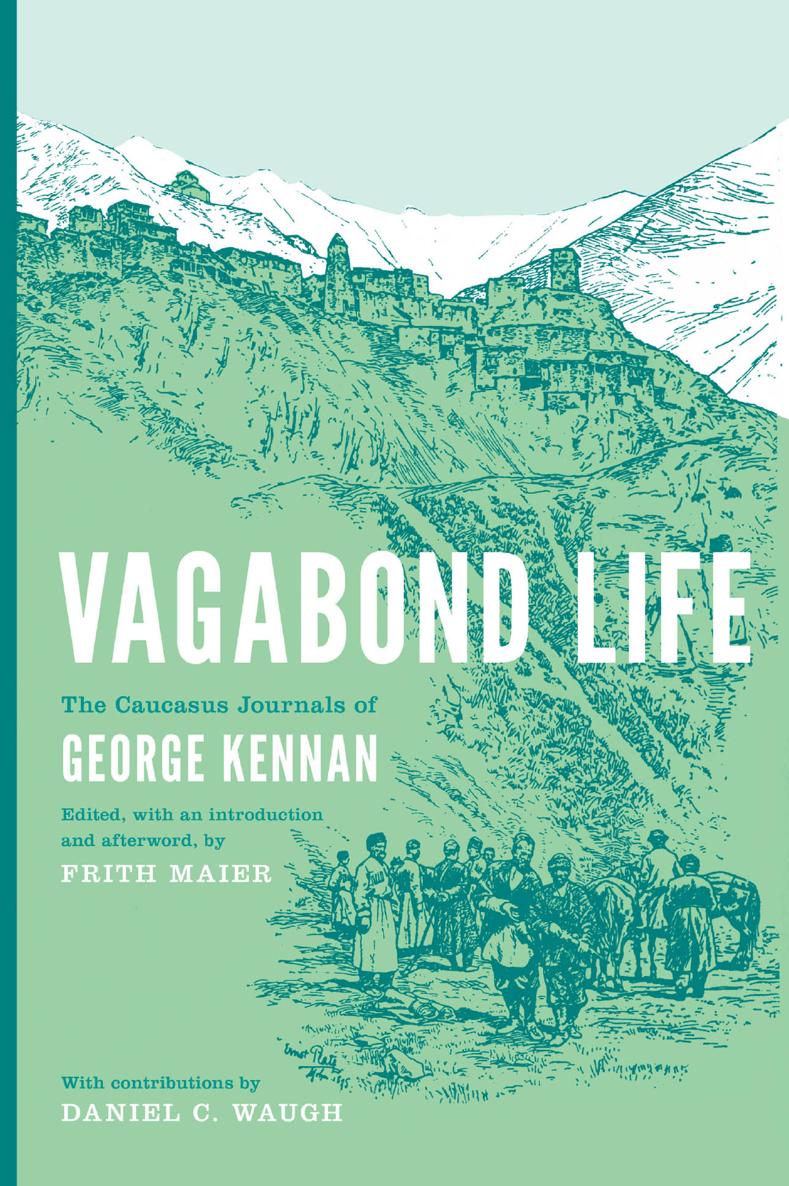

Vagabond life : the Caucasus journals of George Kennan / edited, with an introduction and afterword, by Frith Maier ; with contributions by Daniel C. Waugh.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-295-99487-1 (alk. paper)

1. Kennan, George, 18451924JourneysRussia. 2. CaucasusDescription and travel. 3. RussiaDescription and travel. I. Maier, Frith. II. Waugh, Daniel Clarke.

dk509.k46 2003 2002072783

914.704/81dc21

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

PREFACE

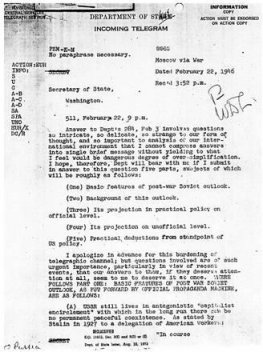

travelers accounts can whet ones appetite for exploration and, when used critically by scholars, may serve as important sources in reconstructing the past and learning about other cultures. The travel writings of George Kennan (a great-uncle of George Frost Kennan, the twentieth-century statesman) are excellent examples. He acquired his reputation as one of Americas first Russia experts from his adventures in Siberia, but few are aware he was the first American to cross the Caucasus from the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea. That trip in 1870 is the subject of this book.

I discovered Kennan when I was a student of Russian and devoured Tent Life in Siberia, his classic book about the 186668 telegraph enterprise that drew him to further exploration in Russia. In the course of my own career in adventure travel, I repeatedly visited Kennans Kamchatka, and the Muslim regions of the Soviet empire claimed my soul for the same reasons that the Orient has always enraptured travelersthe storming of the senses, the escape from a familiar cultural milieu. I rediscovered Kennan in 1996 when filmmaker Christopher Allingham invited me to join him in coproducing a documentary film inspired by Kennans pioneering Caucasus journey. As I explain in the Afterword, by visiting Kennans old haunts and searching out local people whose relatives were on the scene when he passed through, we sought to tell a story about the modern Caucasus, and its traditions.

During the months we spent that autumn in Dagestan and Georgia, we carried with us the typed transcripts of Kennans 1870 journals, which had been buried among the 47,000 items of his archive occupying 57 linear feet of shelf space in the Manuscript Room at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

Kennan never published his Caucasus notes as a book, although he used the material in his popular public lectures and a number of magazine articles, often elaborating on the stories jotted down in the travel journal.

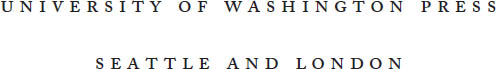

Page 168 in George Kennans Caucasus journal. Courtesy Library of Congress.

This account of Kennans Caucasus journey, which I developed initially as a masters thesis at the University of Washington, presents all but the last few pages of the never-published travel journal, interspersed with excerpts from his letters, articles, and lectures. I have tried to interweave the different source materials in a complementary way. Section 1 covers Kennans journey to the Caucasus, in itself a significant travel feat. Section 2 chronicles his expedition across the Main Caucasus Ridge with the Georgian nobleman Prince Jorjadze. In section 3, he circles back through the lands of Chechnya to slip once again into the Dagestan highlands.

Kennans journals tend toward descriptions of physical geography, while his articles detail more of the human encounters. The writing in the journals is uneven in contrast to the polished prose of the articles he wrote after his return. Yet the journals are refreshing in their matter-of-factness and lack of pretension, even if their observations might not stand the test of modern political correctness. We gain a sense of a man who could endure considerable hardships, cheerfully facing the challenge of what some people he met along the way considered a dangerous plunge into the unknown, and be able to preserve a sense of self-deprecating humor in moments such as this account of a seasick Muslim being given a verse from the Koran dissolved in water to drink for relief from his suffering:

My only regret as I watched this performance was that the Mohammedan method of administering sacred literature in solution was not in vogue in America during my youthful days. If I could only have had the proverbs of Solomon, hymns and the Westminster catechism written on a big platter and washed off with a tumbler of water so that I could have swallowed them at a draughthow many tearful hours I should have been spared.

The published articles and public lectures reflect the fact that Kennans serious study of the Caucasus took place after his travels there and was indeed a life-long project. It is important to remember that the last article was published more than forty years after the trip. His accounts written after his travels often contain stories and dialogue that cannot be substantiated from the journals (although that of itself does not make them improbable) and presumably reflect an effort to appeal to a popular audience. My introduction will discuss Kennans career and his reliability as an observer, and provide a brief background on the Caucasus to aid in appreciating his writings.

Kennan never postured as a Caucasus expert. Yet on his return from Dagestan and Georgia he read everything about the Caucasus he could obtain, thereby becoming a serious scholar of the region at a time when relatively little information was available in English. His journals make a valuable American contribution to a body of late nineteenth-century Caucasus writing that is primarily Russian and British. Kennans travel and exploration writings have been obscured by his high profile political reporting from the 1880s on, but he was truly an adventure travel paragon and an explorer in the greatest sensea student and interpreter of cultures. Determined to learn as much as he could about the Caucasus, Kennan used the trip as an occasion to undertake much more serious study of Russian than he had previously done. He crammed page after page of incisive observations into his journal. He provides insight into the Caucasus at a pivotal point in its historythe period immediately