SOVIET-AMERICAN RELATIONS, 1917-1920

Volume II

The Decision to Intervene

SOVIET-AMERICAN RELATIONS, 1917-1920

By George F. Kennan

Vol. I. Russia Leaves the War

Vol. II. The Decision to Intervene

SOVIET-AMERICAN

RELATIONS, 1917-1920

The

Decision

to Intervene

BY GEORGE F. KENNAN

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

Copyright 1958 by George F. Kennan

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Card No. 56-8382

ISBN 0-691-00842-6, pbk.

eISBN 978-1-400-84385-5

First Princeton Paperback printing, 1989

R0

To

the memory of

two members

of

Americas Foreign Service,

DEWITT CLINTON POOLE

and

MADDIN SUMMERS,

of whose faithful and distinguished efforts

in Russia on their country's behalf

this volume gives only an incomplete account

PREFACE

THIS volume is a direct continuation of the first volume of this series, which appeared under the title Russia Leaves the War. This being the case, there is no need to repeat or to expand the prefatory remarks which introduced the first volume.

I must, however, reiterate here the expression of my indebtedness to the librarians of the Institute for Advanced Study and of Firestone Library at Princeton University;

to the several sections of the National Archives of the United States which have aided my research on this volume;

to the Manuscripts Division of the Library of Congress;

to the Missouri Historical Society and the State Historical Society of Wisconsin;

to the Hoover Library of War and Peace at Stanford University, the Harper Library at the University of Chicago, and the Yale University Library.

In addition, I must add a word of gratitude to the Archive of Russian and Eastern European History and Culture and to the Oral History Research Office, both in the Butler Library at Columbia University in New York, where I received particularly valuable help in connection with this second volume.

I bear a special debt of appreciation to the families of David R. Francis, Allen Wardwell, Thomas D. Thacher, DeWitt C. Poole, and Arthur Bullard for making available memoir material used in this volume.

To Sir Llewellyn Woodward and to the Honorable Norman Armour I am indebted for their kindness in reading large portions of the manuscript and giving me their valuable comments, for the utilization of which I alone bear the responsibility.

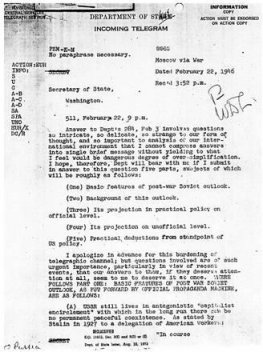

ILLUSTRATIONS

PLATES

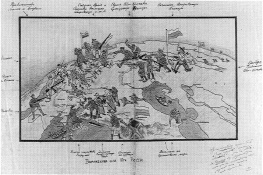

MAPS

The maps were drawn by R. S. Snedeger

SOVIET-AMERICAN RELATIONS, 1917-1920

Volume II

The Decision to Intervene

PROLOGUE

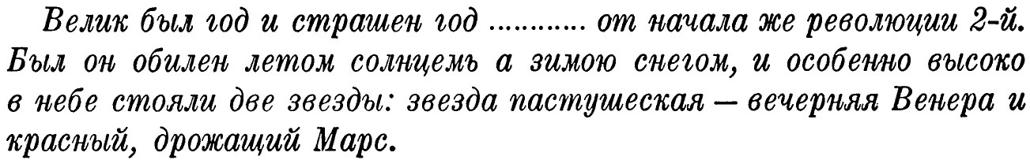

(Great was the year and terrible the year... that followed on the second Revolution. It abounded with sunshine in the summer months, with snow in the winter; and two stars stood out prominently in the heavens: the shepherds starthe evening Venusand the red, vibrant Mars.)Opening words of the great and almost forgotten novel of the Russian civil war,

Byelaya Gvardiya (White Guard), by Mikhail Bulgakov

THE month of March 1918 marked the beginning of the final crisis of the First World War. In the preceding autumn the Allies had been struck by two calamities: the crushing defeat of the Italians on the Po and, even worse, the events in Russiathe collapse of the Russian military resistance, the triumph of the Bolsheviki in Petrograd, the effective departure of Russia from the ranks of the warring powers. Throughout the winter, while Germans and Bolsheviki haggled at Brest-Litovsk over the terms of the peace, a relative quiet prevailed on the western front. It was no secret that the Germans were moving troops and transport from east to west on a massive scale, in preparation for what they hoped would be a crushing and decisive offensive against the Allied forces in France.

In London and Paris, beneath all the embittered tenacity which three and a half years of war had bred, there was an undercurrent of dull apprehension at the realization of the numerical superiority the Germans would now be able to amass in the west. There was no loss of determinationquite the contrary. It was realized that this would be Germanys last great effort, and that if it were successfully contained, the worst would be over. But it promised at least another year of war, and further casualties on a fearful scale.

This appalling prospect, together with the forced lull in military activity at the front, told heavily on the nerves of those concerned with the conduct of the war. The long exertion was now taking its psychic toll. Many people were wretchedly overworked and overwrought. Tempers were frayed, sensibilities chafed and tender. There was, in some quarters at least, a loss of elasticity. Men did their work uncomplainingly, but in a fixed, dogged way, and found it difficult to take fresh account of their situation. February had witnessed a painful readjustment of senior command arrangements on the British side. Inter-Allied military relations were also strained and unsatisfactory, torn this way and that by a never-ending succession of resentments, suspicions, misunderstandings, and political maneuvers. Despite all formal titles and institutional devices, real unity of command was never fully achieved.

At 4:30 a.m. on March 21, after a night of particularly ominous stillness, six thousand German guns suddenly opened up, with a deafening thunder, on the British sector of the front. The dreaded spring offensive had begun. It represented the greatest single military operation ever mounted, to that date. It was designed to split the British sector from the French and to carry the German armies to the sea. The full weight of the attack fell on the British, already worn by years of unremitting losses, effort, and sacrifice. Within the ensuing forty days it was to cost the British army in France some 300,000 further casualties, more than a fourth of the entire force. Not until mid-June would the military situation be stabilized and the state of extreme danger overcome.

Small wonder, then, that as the German offensive got under way a note of sheer desperation entered into the calculations of the British military planners at the Supreme War Council with respect to Russia and the possibilities for reviving the eastern front. The war now hung by a thread. Who knew ?perhaps the thread lay in Russia; perhaps even a token revival of resistance in the east, even the slightest diversion of German attention and resources from the western front, would spell the difference between victory and defeat. If there were even a chance that this was the case, should not every possibility, however slender and implausible, be pursued ?