First published 1979 in Great Britain by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

Transferred to Digital Printing 2007

Copyright 1979 Encounter Ltd.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Encounters with Kennan.

1. United StatesForeign relationsRussia

2. United StatesForeign relations1977

3. RussiaForeign relationsUnited States

4. RussiaForeign relations1975

5. Kennan, George Frost

327.73'047 E183.8.R9

ISBN 0 7146 3132 9

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Routledge in writing.

COVER DESIGN BY ALAN VINE

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent

The Anglo-American world will surely benefit from this collection of pieces dealing with the thought of George Kennan, its course and influence in the past three decades. We associate Professor Kennan, of course, with what came to be known as a "doctrine of containment," the first serious theoretical attempt within the American foreign policy establishment to understand the consequences for world affairs of a suddenly substantial and quite visible Soviet power.

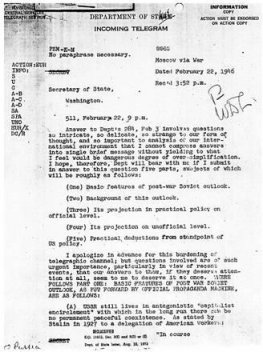

This was a novel development on at least two accounts. First, it necessarily marked a new point of departure in American views of world politics. The Soviet Union was itself a new kind of world power; it proclaimed itself as such; it said it was a state of a new type which, according to its own doctrines, must conduct diplomacy of a new sort. Mr. Kennan's famous 1947 article was entitled "The Sources of Soviet Conduct," which reminds us that we had then to deal with the outward impulses of a totalitarian system whose institutional innards and internal logic could not easily be penetrated.

The second novelty, of course, was his systematic, "European" approach. Americans have tended to believe that doctrine, ideologyeven Historyare things foreign to the nature of the United States. This view was especially pronounced in the realm of foreign policy and diplomacy. Older "alien doctrines" were thought to have drawn the United States into two world wars. Old world diplomatic practices (and perhaps machinations of arms dealers) were once presumed to be the primary barriers to genuine international harmony. Any doctrine, as such, was deemed obscurantist and surely "undemocratic."

Therefore, one surely would sympathize with Mr. Kennan, first, in the effort to create an intellectual scale for weighing American post-war policy and, second, for presenting a doctrinal framework for the conduct of that policy, precisely at a time when people were uninterested in such. Yet one might very well have predicted Professor Kennan's disenchantment with his own "doctrine"! He was always thoroughly grounded in the traditional American view of foreign policy; his memoirs make this plain. Yet he achieved a degree of understanding of the world system far deeper than did many of his contemporaries. Those who notice some apparent changes in his views must confront a curious paradox: both Mr. Kennan's older argument and his own refutation of it are traceable to the same origin, to similar strains in the American tradition.

The problem of how the Western states can accommodate a state of the Soviet type into the larger world system has not yet been solved. The Soviet Union, as an entity, defines its own reason for being precisely in terms of implacable hostility to a liberal world order. That hostility is made manifest not merely in terms of a relentless growth in Soviet military power but also in the Soviets' unceasing political assault, overt and covert, upon the ideas and institutions of the democratic world.

The irony is that the problem seemed far more difficult in 1947 when it was in fact far easier to manage. The West enjoyed absolute nuclear superiority; but beyond that, it had a kind of political, psychological, and intellectual superiority which was everywhere in evidence. The United Nations system was a triumph of Anglo-American theorizing and a reflection of American power in the world at large. The panoply of multinational institutions dealing with problems of finance and commerce was also cast from the Anglo-American mold. The anti-colonial movement was seen, in the main, as the assertion of traditional Western notions about political rights and the rule of law, and was expected to lead ineluctably to the extension throughout the former colonial world of democratic regimes of the Western type. And yet our sense of threat in 1947 was very great indeed.

How should we view our contemporary situation? It is true that developments these past thirty years within the "Soviet empire" have not been wholly to the benefit of Soviet state power. There is first of all the matter of schismthe withdrawal of China, Yugoslavia, and Albania from the Soviet orbit and the perennial threat of political rebellion in Eastern Europe. But though successful resistance to Soviet power may have complicated the Soviets' geo-political situation, it has not undermined the Soviets' totalitarian system. How can we be encouraged, from an examination of the Chinese and Albanian experience, in the hope that the separation of states from Soviet imperial direction necessarily leads to the development of more open societies?

This suggests two important transformations in the quality of our relationship with the Soviet world, two developments which in fact can no longer be comprehended within the older operational implications of the "doctrine" of containment, even if Mr. Kennan were still prepared to propound it as he originally did. First, the unstated premise of the "doctrine of containment" was United States strategic-military superiority. It was the United States which could behave as the militarily ascendant power, projecting its power in various ways and in various places, secure beneath a shelter of strategic dominance. That condition no longer obtains today. The second problem is harder to define, but no less real for that. I refer to important shifts in the general perception of the relevance of societies of the Western type. While we in America may have spoken much of the struggle for "hearts and minds," we have not understood the necessary connection between the Soviets' sense of what is necessary to keep themselves in power and their relentless assault on democratic values. Instead, we pride ourselves in saying that the Soviet "model" has lost validity, that Soviet "doctrine" has become sterile and arid and boring. We assume that our own weariness with the tedious, repetitious, and predictable jargon of the Soviets has affected other groups. We think, in short, that we have achieved a measure of "ideological containment."