Contents

Alastair Sooke

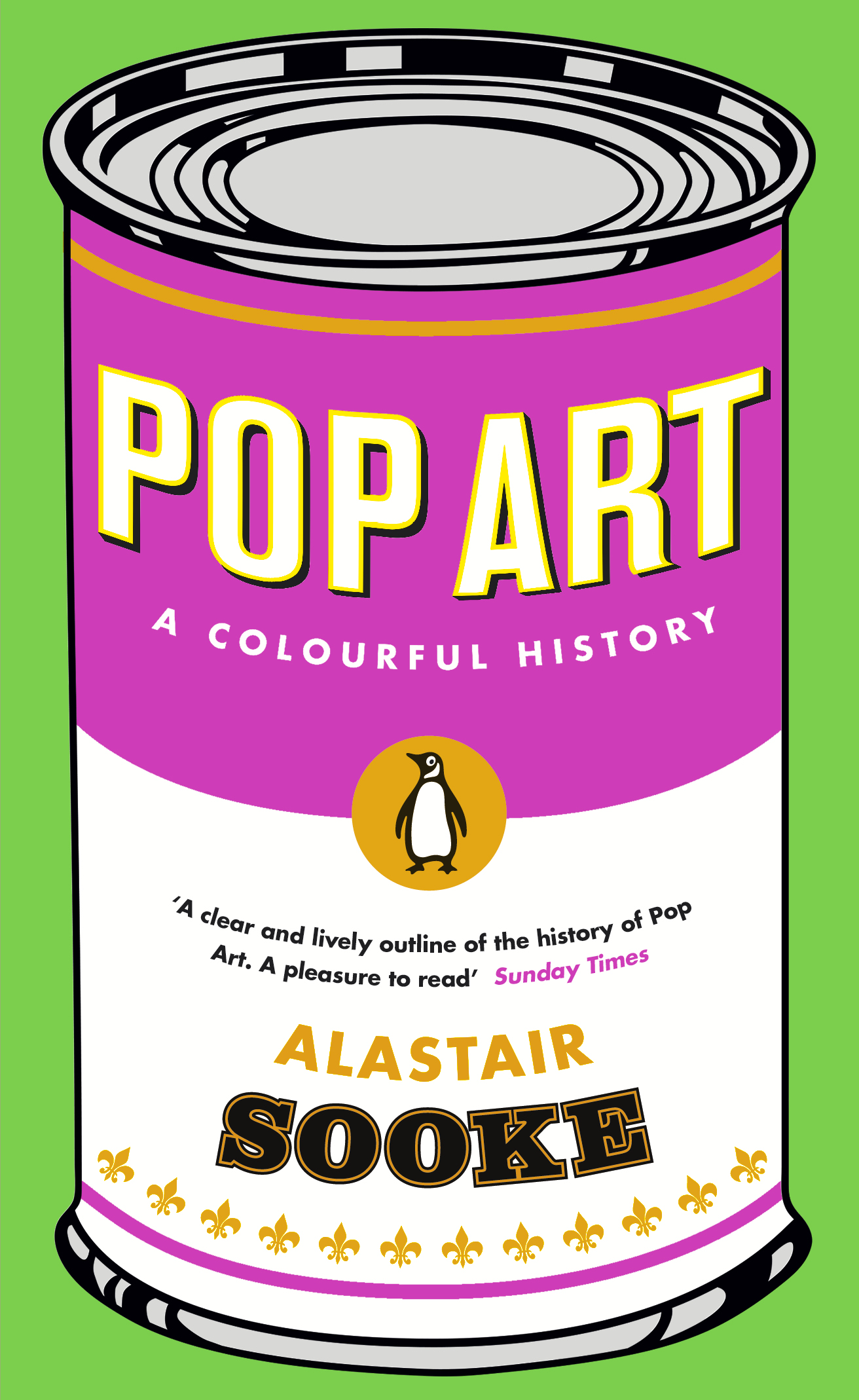

POP ART

A Colourful History

For Tom and Ceridwen

Introduction: Whaam!

After it emerged in nineteenth-century Paris, modern art resolutely refused to pander to mainstream taste. If anything, provocation was its defining trait. Yet, by the beginning of the Sixties, the art world had witnessed so much scandal, outrage, capering and tomfoolery that it was tough to create anything that could jolt people out of indifference. Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Dada: all of these, and more, had made le bourgeois shockproof. The savagery of modern arts sacred monsters such as Picasso had been tamed. As an influential American curator of contemporary art put it in 1962: There no longer is any shock in art. The following year, the American artist Roy Lichtenstein expanded on this theme: It was hard to get a painting that was despicable enough so that no one would hang it. You could practically stick a dripping paint rag in the middle of a gallery, he said, and people would accept it as art. But then along came Pop Art, the most despicable modern movement of the lot, and the shock factor that had gone AWOL from contemporary art suddenly returned: whaam!

Art galleries are being invaded by the pin-headed and contemptible style of gum-chewers, bobby-soxers, and worse, delinquents, the art critic Max Kozloff thundered in the journal Art International in 1962, soon after seeing Lichtensteins first solo show of Pop paintings at the powerhouse Leo Castelli Gallery in New York. In American slang, a bobby-soxer was a teenage girl who was wild about pop music and wore short bobby socks reaching just above the ankle. In other words, bobby-soxers, like gum-chewers or delinquents, did not belong to the ranks of upscale sophisticates who usually frequented Manhattans galleries in the early Sixties. Kozloff concluded: If there is a general rule underlying the new iconography, it is that there is no rule, no selectiveness about it. Anything goes, just as anything goes on the street.

Anything goes: in time, Pops antic, street-smart approach would come to be seen as its greatest strength the zesty X-factor that revitalized moribund modern art. When Pop Art first appeared, though, as Kozloffs remarks suggest, its irreverent energy didnt just irritate people: it made them furious. Take Lichtenstein, that purveyor of highly stylized paintings executed in the manner of cartoons and comic strips. Sometimes described as one of the architects of Pop Art, he provides a useful case study. When he exhibited his Pop paintings at Castellis in early 62, people couldnt stomach them. They certainly didnt try to understand what they were about. His work seemed so crass and vulgar, so frankly idiotic. If it was as straightforwardly dumb as it appeared, then it offered an abominable affront to taste and the time-honoured values of art. And if it wasnt, because it was somehow ironic or tongue-in-cheek, that was even worse, because it turned the people looking at it into the butt of a snide joke. According to Kozloff, it was a pretty slap in the face of both philistines and cognoscenti. Towards the end of the decade, Kozloff who was by then writing as a convert to Pop Art, which had come to be taken seriously by leading institutions and museums around the world recalled the acid shock of seeing Lichtensteins canvases for the first time: To drink in those images was like glugging a quart of quinine water followed by a Listerine chaser. And there was, too, the fierce disbelief that anything so brazen as these commercial icons could have found their way on to prepared and stretched canvas. The very gallery seemed defiled by some quack churl who couldnt, or didnt, adhere to the idea of painting as an easel art. Writing in the immediate aftermath of Lichtensteins debut Pop solo show, another critic was just as blunt: I am interested in Lichtenstein as I would be interested in a man who builds palaces with matchsticks, or makes scrapbooks of cigar wrappers. His art has the same folk originality, the same doggedness, the same uniformity. (See how this writer protected herself from the stink of Lichtensteins paintings by isolating the word art within inverted commas.) The British art critic Herbert Read, who sat on the Tate Gallerys board of trustees during the Sixties, was even terser. Invited along with the rest of the board to consider whether the Tate should buy Lichtensteins large diptych Whaam! (1963), he wrote to a fellow trustee, the sculptor Barbara Hepworth, to express his opinion that the painting was just nonsense. When he was younger, Read had been one of the most prominent champions of modern art in Britain but Pop left him narked and nonplussed: surely, he reasoned, it was a kind of anti-art. At the beginning, then, Pop Art caused pandemonium, scandalizing the tastemakers who believed they knew what art should be about.

*

To our ears, perhaps, such violent reactions may sound surprising. After all, part of the point of Pop was to bring back ordinary objects the sort of stuff commonly encountered out on the street into the lofty orbit of fine art. Over the ages this is something that lots of artists have done. Place, say, a painting of a bunch of asparagus, an ice-cream soda and a packet of cigarettes by the American Pop artist Tom Wesselmann beside a seventeenth-century Dutch still life, and you will find essentially the same idea expressed in different ways: each offers an inventory of mundane consumables in order to provide a snapshot of possibly a comment upon a particular society at a given time. Moreover, modern artists had been raiding the low culture of commercial imagery for generations. Monet and Czanne found inspiration in fashion engravings. Toulouse-Lautrec designed posters inspired by Pariss nocturnal demi-monde. Picasso conjured witty wordplay by incorporating real-life advertisements and newsprint into his Cubist compositions. Bacon made paintings inspired by well-worn scraps of photography culled from books, newspapers and magazines. He was also interested in working with imagery from films. Pop artists would have recognized all of these strategies and techniques. Then there were the modern artists who seemed to be creating something uncannily like Pop long before the movement had begun. The American artist Stuart Davis painted commercial products during the Twenties, including a packet of Lucky Strike loose tobacco and a bottle of Odol mouthwash. In doing so, he anticipated one of the central strategies of Pop Art: foregrounding well-known brands. Almost two decades before Andy Warhol decided to paint a Coke bottle for the first time, Salvador Dal placed a meticulously rendered Coca-Cola bottle centre-stage in his oil painting Poetry of America (1943). Arguably, then, a Pop impulse if by Pop we mean broadly an interest in commonplace imagery and the popular arts has always been a strong component of modern art.

So why the big shock when Pop Art suddenly arrived? One obvious explanation is that it looked so radically different from the principal style of modern art then dominant in America: abstraction. Thanks to an influx of important migr European artists during the Second World War, New York in the Forties suddenly found itself superseding Paris as the capital of world art. Inspired in part by French Surrealism, a new school of painters emerged who came to be known as the Abstract Expressionists. These artists included the likes of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. They had a reputation as impassioned, heavy-drinking, almost mythical bohemians, who took painting very seriously indeed. Abstract art, for this macho tribe, was about baring the chest and revealing the soul. It was a difficult journey inwards to articulate the