Published with support of the Susan E. Abrams Fund

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2018 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2018

Printed in the United States of America

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-55161-6 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-55175-3 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226551753.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Barton, Ruth, 1945 author.

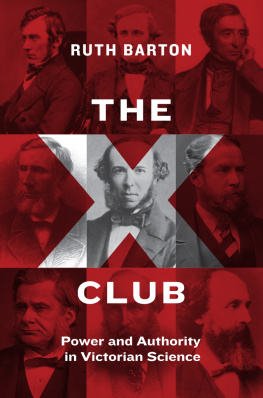

Title: The X Club : power and authority in Victorian science / Ruth Barton.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017049912 | ISBN 9780226551616 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226551753 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: X Club (London, England) | Science clubsEnglandLondonHistory19th century. | ScienceEnglandHistory19th century. | London (England)Intellectual life19th century.

Classification: LCC Q41 .B37 2018 | DDC 506/.0421dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017049912

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

The X Club 186492

- George Busk (18071886)

- Joseph Dalton Hooker (18171911)

- Herbert Spencer (18201903)

- John Tyndall (ca. 18221893)

- Thomas Henry Huxley (18251895)

- William Spottiswoode (18251883)

- Edward Frankland (18251899)

- Thomas Archer Hirst (18301892)

- John Lubbock (18341913)

I have lived with these nine men for decades.

Some were easier to live with than others. Busk was calm and reliable. He was the man in the background who brought many of Huxleys projects to completion.

I like and admire Huxley, the witty, brilliant, egg-dancing controversialist, but also effective committee man and administrator. He was thin-skinned in his early years and, throughout his life, overready to find enemies. According to Marian Evans (George Eliot), who knew him for thirty years, he needed an enemy to attack; in later life, he found that controversy helped him to overcome depression. Huxley initially learned political strategy from Hooker, who had the benefit of birth into a botanical dynasty.

Hooker, who had a strong sense of social and scientific hierarchy, set high standards for scientific achievement and gentlemanly deportment. Although he was usually discreet and gentlemanly in public, he could be a harsh critic behind a friends back. Compared to Huxley, Hooker was privileged, but social tensions within his family left something of a chip on his shoulder.

Tyndall, the brilliant experimentalist, flamboyant lecturer, and dinner party conversationalist, was often seen as Huxleys alter ego. Although like Huxley in many ways, he was not an easy friend or colleague. He could be moody and self-righteous and was unable to laugh at himself. Even Hirst, his admiring protg, found him trying at times. I admire the self-discipline that enabled him to rise from Irish village to London high society; I sympathize with the high psychological price he paid in decades of headaches, indigestion, and insomnia; but I find his argumentativeness tiring and am unconvinced by his self-righteous rationalizations for entering yet another controversy.

Hirst could be ponderous and preoccupied with his own small affairs. Sometimes, perhaps, this could be explained and excused by his bad health. He was a loyal and forgiving friend. He was retiring, dignified, and, mercifully, unlike his better-known X-brothers, not argumentative.

Frankland was more introverted than most of his fellows. (His biographer, Colin Russell, says there was a family scandal to hide.) His warm early friendships with Tyndall, Hirst, and Hooker cooled over time, for reasons over which I can only speculate.

Spottiswoode, a wealthy businessman, was generous and sociable. He was a willing and effective supporter of many projects initiated by his friends, and often calmed the waters that they stirred up. He had a reputation as a witty dinner companion, but I saw little of this. I suspect that, until his untimely death, he helped to calm frictions within the Club.

Lubbock was by far the youngest of the group, almost ten years younger than all but one of the others, but he was born to scientific and social leadership. Unlike many of his X Club fellows, who had struggled to find a place in science, Lubbock was blessed with wealth and self-confidence. His social position made him useful in many group campaigns. His wife, Nelly, enjoyed his scientific friends, hence their large (and well-staffed) country house became one of the social centers of the group.

Finally, there was Spencer, our dear Diogenes, whose many quirky principles made life difficult for both his friends and himself. He became more self-important and opinionated over time, and even his greatest admirers in the Club criticized him bitterly. Much can be explained by his emotionally bleak childhood and idiosyncratic upbringing, but that does not make him more likeable.

These nine men formed a dining club at the end of 1864. They intended to meet monthly, from October to June. Their meetings in Londons fashionable west end continued for almost thirty years, until early 1892 when Hirst died. Spottiswoode and Busk had already died, most of the others were in decline, and those few who survived in good health had loose emotional ties to the group.

In 1864 they were energetic and ambitious and, with a few exceptions, already warm friends. The formal club developed from two earlier friendship trios. Hooker, Busk, and Huxley were naturalists, each with experience as navy surgeons. Busk, the oldest by ten years, was fifty-seven. A decade previously, he had retired from medical practice to devote himself (as the Victorians said) to science. In 1864 he was pursuing his anatomical research and working tirelessly in the administration of many scientific societies. His earlier research had focused on microscopic organisms, but in the early 1860s he sought out sites of human prehistory and became an expert on the newly significant topic of craniometry. Hooker, second in age and first in scientific eminence, was forty-seven. He was acknowledged as the leading botanist in Britain and held the position of assistant director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew under his father, Sir William Hooker. He was also first in political skill. Over the preceding decade, he had often stirred up his friends to collaborate in various reforming and lobbying schemes. The idea of starting a club was his. Huxley was younger again, thirty-nine, and after years of struggle had secure but modestly paid employment as professor of natural history in the Government School of Mines and naturalist to the Geological Survey. Huxley and Hooker felt that their being well-salted by long scientific voyages made them brothers. Busks experience of the sea, as surgeon on the merchant navys hospital ship moored at Greenwich, was not in the same league, but he shared scientific interests and reforming ideals with Hooker and Huxley. These three had been friends for a decade.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).