CASS LIBRARY OF AFRICAN STUDIES

GENERAL STUDIES

No. 76

Editorial Adviser: JOHN RALPH WILLIS

Centre of West African Studies, University of Birmingham

.

KILIMANJARO

AND ITS PEOPLE

A History of the Wachagga, Their Laws, Customs and Legends, together with Some Account of the Highest Mountain in Africa

by

CHARLES DUNDAS

Published by

FRANK CASS AND COMPANY LIMITED

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

First edition 1924

New impression 1968

Transferred to Digital Printing 2005

ISBN 0 7146 1659 1

INTRODUCTION

LIVING in the shadow of one of Earths most magnificent structures, one senses a mental attraction akin to the physical magnetism exercised by great over minute bodies. Irresistibly the eye is focussed on the imposing mass, and as it rests on the beauties of slope and ravine, forest and ice field, the mind must bear it company, dwelling on their meaning, and speculating on their secrets.

The colossus teems with life, vegetable and animallittle known heroes in the struggle for existence. But there, on the fringe of the Kilimanjaro, are also human dwellers who have made it their home. Where once fire and torrent destroyed and built, the day is seething with industry and the night throbs to the breathing of countless children of the mountain.

How long were they there, what life have they evolved, what aspirations are theirs, and what does the future promise them? These are questions that force themselves on the stranger in their midst.

To the writer the pursuit of this study has seemed less induced by mere interest for research than compelled by the spell of the mountain. The study of any primitive people has its fascination, but as one who has oft-times been under this influence, I can say that never have I experienced an equal degree of allurement as has prompted my researches among the Wachagga. Far be it from me to give entire credit for this power to the mountain alone; it is rather the combination of nature and humanity which is here observable in its most attractive and interesting form; the one is a compliment to the other, both are individually full of interest and mutual exponents of each others merits.

It may be this factor which has produced more fruitful results than I have achieved elsewhere. Yet I must admit, also, that never have I found a tribe so responsive to sympathetic study, none so ready to frankly discuss their traditions and habits, as are the Wachagga. A more delightful surrounding, a more interesting study, and a more encouraging subject, could hardly be found in Eastern Africa, and if the following presentation thereof seems to disprove this assertion, it is no reflection on the mountain and its people.

My interest was first awakened by the thoughtful writings of Bruno Gutmann whose researches it has been my object to amplify. Excepting for this ground work, my thanks are due to the natives themselves, but more particularly to two, Nathanael Mtui and Joseph Merinyo, both Christians, pupils of Gutmann and examples of the truth that, given wise teaching, the African may still be appreciative of and faithful to his traditions, whether he be pagan or Christian.

C. D.

CONTENTS

VIII. OCCUPATIONS AND INDUSTRIES

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

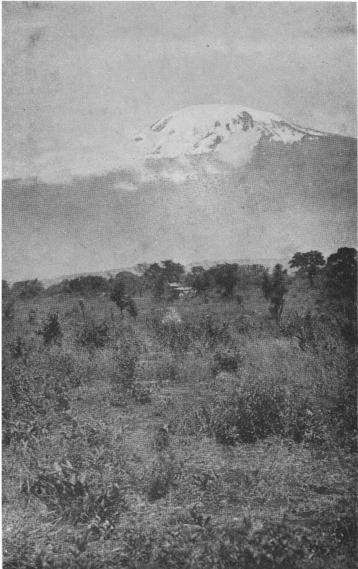

KIBO, 19,700 FEET

MAP

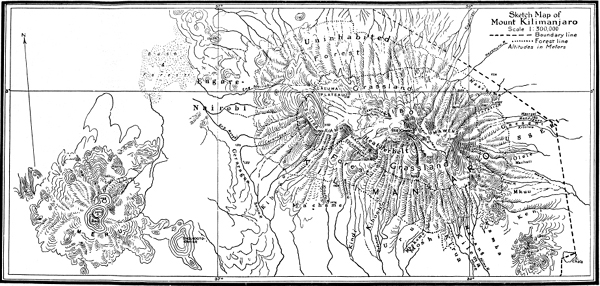

SKETCH MAP OF MOUNT KILIMANJARO

CHAPTER I

KILIMANJARO

ON November 10th, 1848, the German Missionary Rebmann wrote in his diary: This morning we discerned the Mountains of Jagga more distinctly than ever; and about ten oclock I fancied I saw a dazzlingly white cloud. My Guide called the white which I saw merely Beredi,cold; it was perfectly clear to me, however, that it could be nothing else but snow.

That anyone who had once seen the great glittering dome of Kilimanjaro could doubt it to be ice capped is out of the question, yet even when Rebmann had traversed the mountain flanks his accounts of the snow-covered summit were described by one writer as a most delightful mental recognition, only not supported by the evidence of his senses. This sneer appeared in a publication of 1852 most inappropriately entitled Inner Africa Laid Open, since it knew nothing of one of the most conspicuous marvels of Inner Africa. Perhaps the author of that work should be pardoned for doubting the existence of so remarkable a mountain which yet was unknown until Rebmann saw it. In these days when one may have the closest view of the great mountain from a railway, it seems indeed difficult to conceive that it was unheard of seventy-three years ago.

The fact that it was so, is a powerful reminder that despite railways or any other modern conveniences, whereby the darkness of Africa has been rapidly dispelled, we are after all traversing regions that are little more than virgin tracts.

Kilimanjaro is beautiful in detail, but no less so in its general form, and must be almost unique for its individual grandeur. There are some fifteen other points of the globe which exceed it in height but they are mostly the highest summits of mountain masses hardly distinguishable as individual heights. Kilimanjaro on the other hand rises from a level plain lying 2,500 to 4,000 feet above sea-level, and mounts in sweeping lines from a base of less than 40 miles in diameter to an altitude of over 19,000 feet above sea-level. It has but two definite peaks, the great ice dome called Kibo, and the jagged rock peak Mawenzi, which is over 17,000 feet high and. is connected with Kibo by a gracefully curved saddle some five miles in length. From any point in the plain you may see the whole base a few miles distant and view the mountain from that base to the summit. Seen so closely the mountain seems to lose in height, and nothing but the fact that close to the equator one is looking at ice fields which are some 5,000 feet in perpendicular can make you realize the great height of the mountain. I have seen Kilimanjaro from a distance of 120 miles or more and it appeared stupendous, but whether one views it from afar, or from the adjoining hot tropical plain with the alluring scene of ice fields above, whether you stand on its fertile flanks looking up to the dazzling white dome and down to the bush covered plain, or whether you breathe the crisp air of the snow line gazing up at the green glint of ice, with the heather-covered land around, and the vast panorama below; in the clearness of early morning sunshine, in the gorgeous colouring of sunset; shining in midday glare, or.veiled in light mist, or cloaked in thunder clouds, it is an inspiring sight which compels the traveller to accept it as one of the worlds wonders.

The detailed loveliness of the mountain can only be appreciated by those who have seen it step by step from base to summit and have observed its variety of beauty and life. From the plain we may mount the gentle slope, first through uninhabited bush land following one of the long ridges that flatten out into the plain. We come on a belt of coffee plantations beyond which we enter the Chagga country at about 4,000 feet above sea-level. And soon we are in the shade of continuous banana groves in which lie snugly the huts of the mountain dwellers. Gracefully crowned trees abound, giving the surroundings a parklike appearance. Some of the trees are giants and recognizable as the survivors of a primeval forest that once stretched down to the plain but had to give place to the industry of the early tillers of the virgin soil. As we go higher the ridges narrow and are divided by deep ravines carved by the rapid flowing mountain streams. Here and there they run through small meadows grazed by a pygmy breed of cattle, or course through tiny gardens. The path is traversed by innumerable furrows conducting water to the fields and groves from main branches that run along the steep valley sides and carry the water hundreds of feet above the bed of the river. The whole is a picture of sunshine mingled with vivid green, of peaceful industry and luxuriant fertility. On we go, pursuing the bright red line that betrays our path ahead in the sea of green; we seem to have mounted high but feel miserably in the dust whenever a bit of open land permits us a glimpse of our ultimate goalthat shining white snow field which seems as far away and serene as ever. Soon we see bracken and brambles, and the sides of the furrows are bright with green moss, tiny ferns and gay coloured flowers. The huts are fewer, the banana groves more isolated, and we reach the limit of human habitations. We may estimate our altitude at 6,000 to 7,000 feet, for higher than that the Chagga people do not live. Beyond this we enter on a belt of high bush interspersed with bracken. This zone is comparatively narrow, an hour or two more will show us higher growth, and forest surrounds us. Soon we find the ground carpeted with moss, the trees grow twisted and are bedecked with small ferns, orchids, green moss, and parasites of all sorts. Delicate wild flowers abound underfoot and hang in clusters from vines overhead. The ridge we follow is flanked by deep ravines, on the precipitous sides of which tree ferns and wild banana flourish. Many a waterfall roars down perpendicular cliffs or trickles over rocky inclines into crystal clear pools set in a riot of jungle growth. Denser and denser grows the forest, more and more twisted and moss-grown the trees, for here it is almost always moist; overhead the trees are wet from the morning mists, underfoot the slopes are honeycombed with springs that well forth at every step.