Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the Print Version

Nightboat Books encourages you to calibrate your text size using the line of characters below:

Lorem ipsum dolor eros amet, consectetur adipiscing ac mi aliquet magna.

When this text appears on one line on your device, the resulting settings will most accurately reproduce the layout of the text on the page and the line length intended by the author. Viewing the title at a higher than optimal text size or on a device too small to accommodate the lines in the text will cause the reading experience to be altered considerably; single lines of some poems will be displayed as multiple lines of text. If this occurs, the turn of the line will be marked with a shallow indent.

By the same author

POETRY

The Revisionist and The Astropastorals: Collected Poems

CRITICISM

Amerifil.txt: A Commonplace Book

BIOGRAPHY

Both: A Portrait in Two Parts

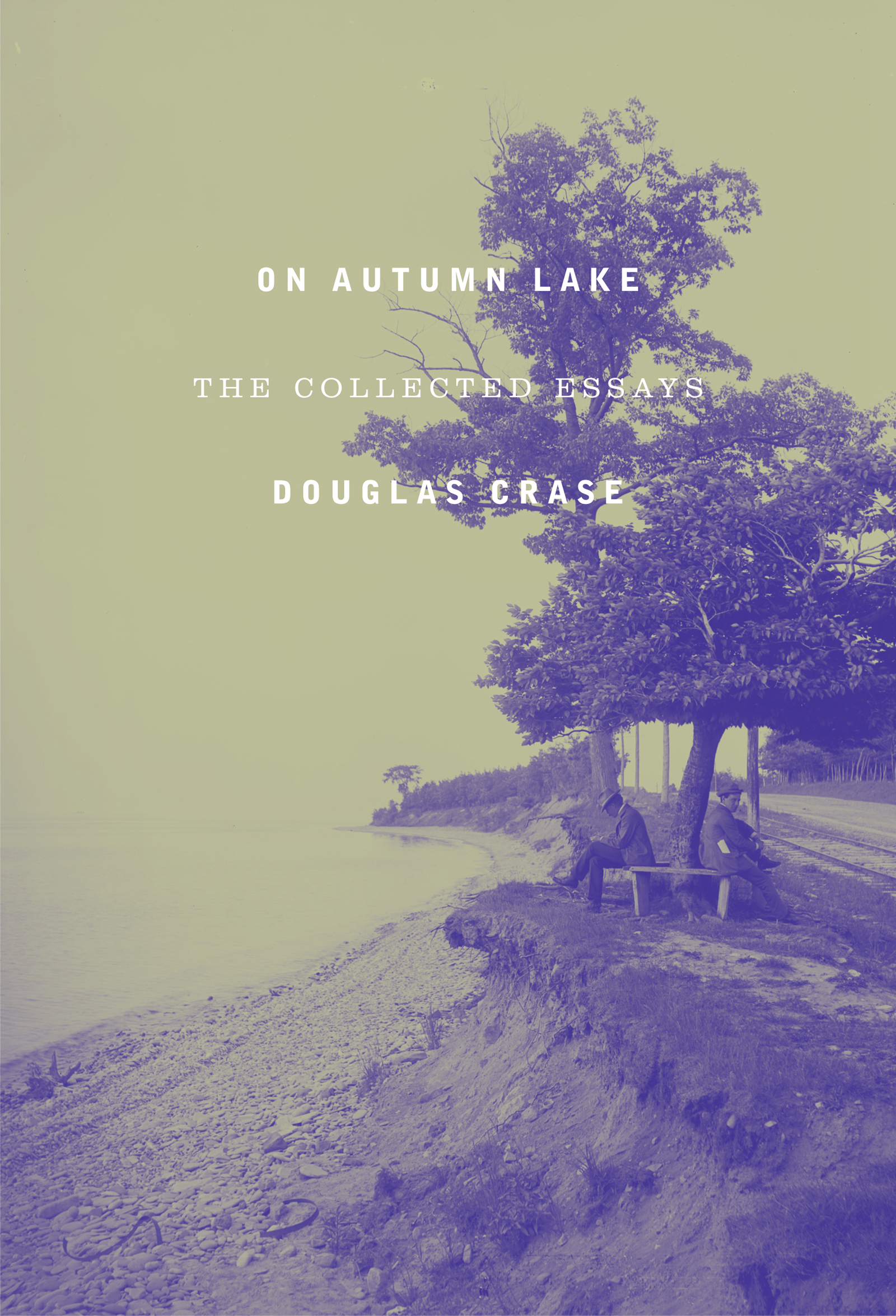

ON AUTUMN LAKE

THE COLLECTED ESSAYS

DOUGLAS CRASE

NIGHTBOAT BOOKS

NEW YORK

Copyright 2022 by Douglas Crase

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States

Print ISBN 978-1-64362-143-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-64362-161-6

Cover photo: Detroit Publishing Co., Lake Ontario from the boulevard,Oswego, N.Y. [between 1890 and 1901]. Library of Congress.

Design and typesetting by Crisis

Typeset in New Caledonia

Theres a better shine, How bright youll find young people and excerpts from Lake Superior by Lorine Niedecker, copyright 1985 by the Estate of Lorine Niedecker, reprinted by permission of Bob Arnold, literary executor for the Estate of Lorine Niedecker.

Rain Moving In from A Wave by John Ashbery, copyright 1984, 2008 by John Ashbery, all rights reserved, reprinted by permission of Georges Borchardt, Inc.

A Hidden History of the Avant-Garde, copyright 2011 by Douglas Crase, reprinted from Tibor de Nagy Gallery Painters & Poets by permission of Andrew Arnot for Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York.

Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress

Nightboat Books

New York

www.nightboat.org

PREFACE

If theres anything to explain about this book its that I never planned to write criticism and, no matter the appearance of the pages that follow, I never did. A critic, as defined by Randall Jarrell with more than a hint of irony, is someone who protects you from the bad poems you shouldnt let yourself read, and by extension, I suppose, from the bad art you should be careful not to see. One would have to read all the poets, see all the art, to be of any use in such a job, which means the critics must suffer the very exposure they warn the rest of us to avoid. Id retreat from the task before it was even begun. The essays here must belong in some other category; they are appreciations or predilections, though to be truthful they were more like affairs of the heart, affairs of attention and intellectual desire, rather than criticism.

I didnt plan a life in literature, either. In college I toyed briefly with the prospect of switching from pre-law to the recently organized and optimistically named program in American civilization. My temptation was thanks to Wallace Stevens, whose insistent cadence I encountered in an elective during the second year. I went so far as to show poems of my own to the professor, emboldened, no doubt, because he wore boots, a leather jacket, and sometimes arrived for class on a motorcycle, all of which lent him considerable authenticity in the eyes of a college sophomore. This was the professor who tactfully advised me later that poetry is an avocation, not a vocation. By then I was in law school, so perhaps he thought his advice would do no harm.

Another two years were required before I abandoned law school for good, a liberation I owe to the life-altering influence of heroes, including Stevens, and friends. Heroes and friends were to be the visible saints who supplied by their example the education I missed in school.

An education by friends, in my experience, is an education by enthusiasm and reproach. Nobody in their proud twenties wants to play the sedulous ape; but to adopt the passions of a lover or a friend, to try them on like clothes even if you must painfully outgrow them, has to be one of the most glorious paths to an advanced degree. The drawback to the curriculum is that it leaves blind spots. You can emerge from your education by heroes and friends lacking a certain conventional balance, partial for the rest of your life to a set of values acquired when you were the fool of love. I wouldnt have it any other way.

Still, I was surprised to discover from a trial arrangement of these essays that their strict chronology put a piece on landscape as first in the book. I shouldnt have been. Land use in America, urban and rural, was an early obsession. One evening at dinner in the apartment I shared with my partner, now husband, Frank Polach, our friend James Schuyler took a long look around the room where the books were stacked in piles on the floor. Every book I see in this room has the word America or New York in its title, he gently observed.

If this was a limitation, it didnt bother me. I had been won over by Gertrude Steins remark in her lecture What Is English Literature? that she was content not to know everything. In fact, she was more than content. I know that one of the most profoundly exciting moments of my life, she said, was when at sixteen I suddenly concluded that I would not make all knowledge my province. In an age of information overload, her wisdom is more thrilling by the day.

Within the province of my interests I seemed to narrow the focus even further. Whether this was by default or design is no longer important, but it did register as a conscious decision at the time. I wanted a life to be partial to; wanted to know things like the hedgehog instead of the fox, or, to pick a more vividly North American metaphor, I wanted to travel a good deal in Concord. I wanted this because Id developed the idea from subjects in history and political science that knowing one thing in depth would make an emblem for knowledge elsewhere, that knowledge in all its diversity was nonetheless, in its internal density, complexity, and structure, isotropic in all directions like the universe.

Say youve decided to read all of a single author, as I did Emerson, or as Susan Howe must have done with Dickinson; read them as if no one had read them before, and only afterward consult the established critical writings on that author. You soon note that the writings generalize where they might be particular. They elaborate on their learning, impressions, and at times their prejudice, until it appears eventually they have substituted the elaborations for what the author actually wrote. Jarrell cautioned his readers to remember that the criticism of any age, even the best of it, becomes inherently absurd. Sometimes its risible. And the conclusion is: if they got Emerson wrong, or Dickinson, how can I believe what they are telling me about Ashbery, or Niedecker, or the origins of the New York School?