For Asya Muchnick, whose editorial letters should be framed; for Jennifer Rudolph Walsh, whose savvy and humor make her a joy to work with; for Michael Pietsch, a publishing gentleman and my gracious former editor; for Elinor Lipman, from whom I have learned much about being a human being, both in writing and in life; and for John Osborn, who with a single sentence of advice stripped away a large and potentially fatal part of this book. Without him, nothing would be possible.

Testimony

Body Surfing

A Wedding in December

Light on Snow

All He Ever Wanted

Sea Glass

The Last Time They Met

Fortunes Rocks

The Pilots Wife

The Weight of Water

Resistance

Where or When

Strange Fits of Passion

Eden Close

ANITA SHREVE is the acclaimed author of fourteen previous novels, including Testimony; The Pilots Wife, which was a selection of Oprahs Book Club; and The Weight of Water, which was a finalist for Englands Orange Prize. She lives in Massachusetts.

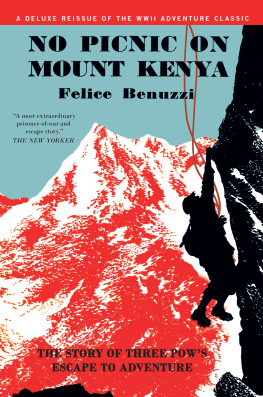

W ere climbing Mount Kenya. Not this Saturday, but the next.

Patrick made the announcement as he moved into the guest room of the Big House, the plumbing in their own small cottage currently disabled. Patrick spoke of the climb without fanfare, as he might a party in two weeks time. They were young, each twenty-eight. Theyd been in the country three months.

Despite the heat, Patricks shirt still held its creases. James, whose black skin shone blue in the planes of his face, washed their clothes in a bathtub, hung them to dry, and pressed them with an iron that made the fabric hiss. Not even the equator could undo Jamess creases.

Patrick set his doctor bag and his briefcase on the floor. He had shaved his beard as a gesture of respect but wore his black hair longer than most.

Arthurs arranging it. It takes four days. Porters will carry the provisions.

When Margaret and Patricks toilet in the cottage had ceased to function, theyd temporarily moved in with their landlords, Arthur and Diana, who lived two hundred feet away in the larger house on the property.

Well camp? Margaret asked.

There are huts.

In a few minutes, Margaret would dress for dinner. Under her palm, she could feel the distinctive stitching of the white coverlet. Id better buy hiking boots, she said.

Beyond the casement window, there was birdsong, noisy until early evening, when the day would be snuffed out, at the same hour, every day, summer or winter. In Africa, Margaret often felt dazed, as if something shiny had hurt her eyes.

Who will go? she asked.

Arthur and Diana. You and me. Arthur mentioned another couple, but I forget their names.

You can take the days off?

Patrick shrugged his shoulders, indicating a flexible schedule. He moved to the bed and sat beside Margaret, making a deep V in the soft mattress. Despite the heat, he wore long trousers, another gesture of respect. In Kenya, African men emerged from mud-and-wattle huts in suits to drive matatus or to sell scrap metal or to cut meat. To dress casually was to flaunt the ability to do so, as well as to advertise oneself as an American. Only American and German tourists dressed like children.

You okay? Patrick asked.

His eyes were light blue, sensitive to the sun. When outdoors, he always wore dark glasses.

Im fine, Margaret said.

You seem quiet.

How was your day?

I was mostly at the hospital. What time is dinner?

The house ran with the precision of a fathers watch. They had been Diana and Arthurs guests for five days, a decent plumber apparently difficult to obtain. First a message had to be sentthe plumber didnt own a telephoneand the problem described. A fee would have to be negotiated, and then transportation sorted. The particular plumber Diana liked was said to be visiting his wife in Limuru. It was unclear when he would return.

Margaret wanted to ask if another plumber could be found, but to do so would be to seem ungrateful for the hospitality. Patrick and Margaret were, after all, being housed and fed.

Seven, Margaret said of dinner.

Patrick asked her if she had ever climbed a mountain. As he did so, he took her hand. He often took Margarets hand, in public as well as in private. It meant I am suddenly thinking of you.

Though Patrick and Margaret had been together for two yearsmarried five monthsentire landscapes of their individual pasts were unknown to the other. Margaret told Patrick that she had once climbed Mount Monadnock, a lesser New England peak. Patrick said that he hadnt ever climbed a mountain, being a city boy from Chicago.

The smell of boiling horse meat made its way into the bedroom. It was an awful smell, and Margaret was certain she would never get used to it. The meat was for the dogs.

Do we need, I dont know, instruction? Margaret asked.

Im sure Arthur will have it all in hand.

The meat would be something James had purchased at the duka earlier in the day, the blood soaking the Kenya Morning Tribune used to wrap it. It would not be any different from the beef Margaret bought for Patrick and herself, the steaks too fresh, not aged, and therefore tough, tasting of animal. How tall is Mount Kenya?

Seventeen thousand feet, give or take.

Thats over three miles high.

Were already a mile above sea level just sitting here. And I think we probably gain some altitude driving to the mountain.

So Kilimanjaro is higher? Margaret asked.

Higher but easier. I think you simply walk to the top. In large circles. It takes a while, but most amateurs can handle it. Its supposed to be fairly boring.

Patrick changed out of his brown leather everyday shoes, which were covered with mud. If he left the shoes outside the door in the evening, they would be clean in the morning.

We dont walk?

We climb. We hike. Parts of it will be rough.

Margaret imagined Dianas Land Rover, packed with gear, journeying through the shimmering lime-green tea plantations shed seen only from a distance.

The guest room seemed to have been designed for a writer or a scholar. Margaret sometimes sat at the heavy carved desk, on which an antique typewriter had been placed. Shed tried it once, wincing at the hard thwacks the keys made, as if something delicate and tentative were being announced with a tattoo.

The desk chair had carved arms and a nearly silver patina. On the walls were photographs of people she could not identify, a wooden shield that had perhaps been used in battle, and a sunburst design of spears. The books were leather-bound and uniform and, to judge from their condition, often read. Margaret imagined an early settler, the books all there were available to him of the printed word in Nairobi, reading and rereading them by lantern light. She sometimes held one in her hands.

On the other side of the room was a skirted dressing table of the sort one used to see in old movies. On its glass surface were cut-crystal jars with silver tops. Perhaps the room had belonged to Dianas parents when they built the house in the late 1940s. Theyd come out from England after the war to try their hand with horses. Margaret picked up a picture of the couple, extravagantly dressed, looking as though they were about to head off to a party at the Muthaiga Country Club. The fathers face was weathered; the mother had a small, sweet smile. Diana, as a child, would constantly have heard that she resembled her father.

Margaret thought about the story of the young Masai whod been invited by an American benefactor to use his wit and innate intelligence to make a go of it in New York City. Two months after the young mans arrival, he jumped to his death from his tenth-story apartment window. She thought the Masais heart must have grieved for the Rift Valley or that his senses had been violated by the citys gray geometry. The anecdote was meant to be a cautionary tale, though Margaret was never quite sure what exactly was being cautioned. One shouldnt be taken out of ones environment? Or, if so, might one, at any moment, be subject to dangerous derangement?