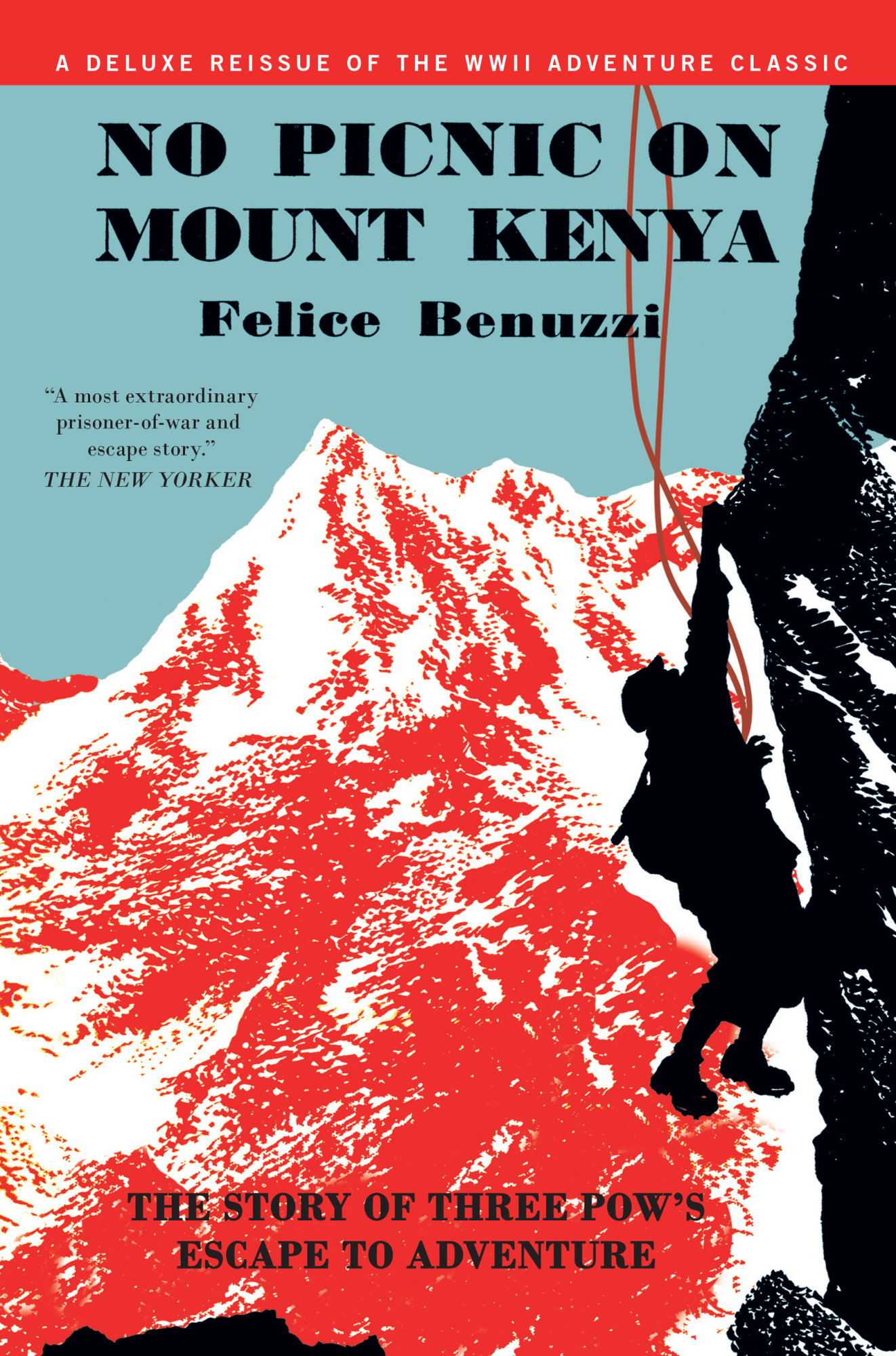

Felice Benuzzi (Bartolini, Paris, 1949)

MacLehose Press

An imprint of Quercus

New York London

1947 by Felice Benuzzi

Cover design adapted from the Dutton first edition, New York, 1953

This edition published by Quercus in the United States in 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to .

eISBN 978-1-68144-015-6

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Distributed in the United States and Canada by

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

www.quercus.com

CONTENTS

I would like to thank:

First of all my companions Dr. Giovanni Balletto, Dodoma, Tanganyika Territory, and Mr. Enzo Barsotti, Mombasa, Kenya, who appear in this book as Giun and Enzo, and without whom neither our adventure nor the writing of this book would have been possible.

All our fellow prisoners of war of POW Camp 354 who assisted us in the actual escape and gave us their generous and silent assistance during the period of preparation and organization.

Mr. R. M. Graham, Acting Conservateur of Forests, Nairobi, Kenya, not only for having assisted me with invaluable information but also for having attempted to convert my English into a more readable language, and Mrs. Graham, Dr. J. D. Melhuish and Mr. E. Robson, M.P.S., for having assisted me with much advice.

The Mountaineering Club of East Africa for having given permission to quote some extracts from their Journal Ice Cap.

F.B.

The Mirage

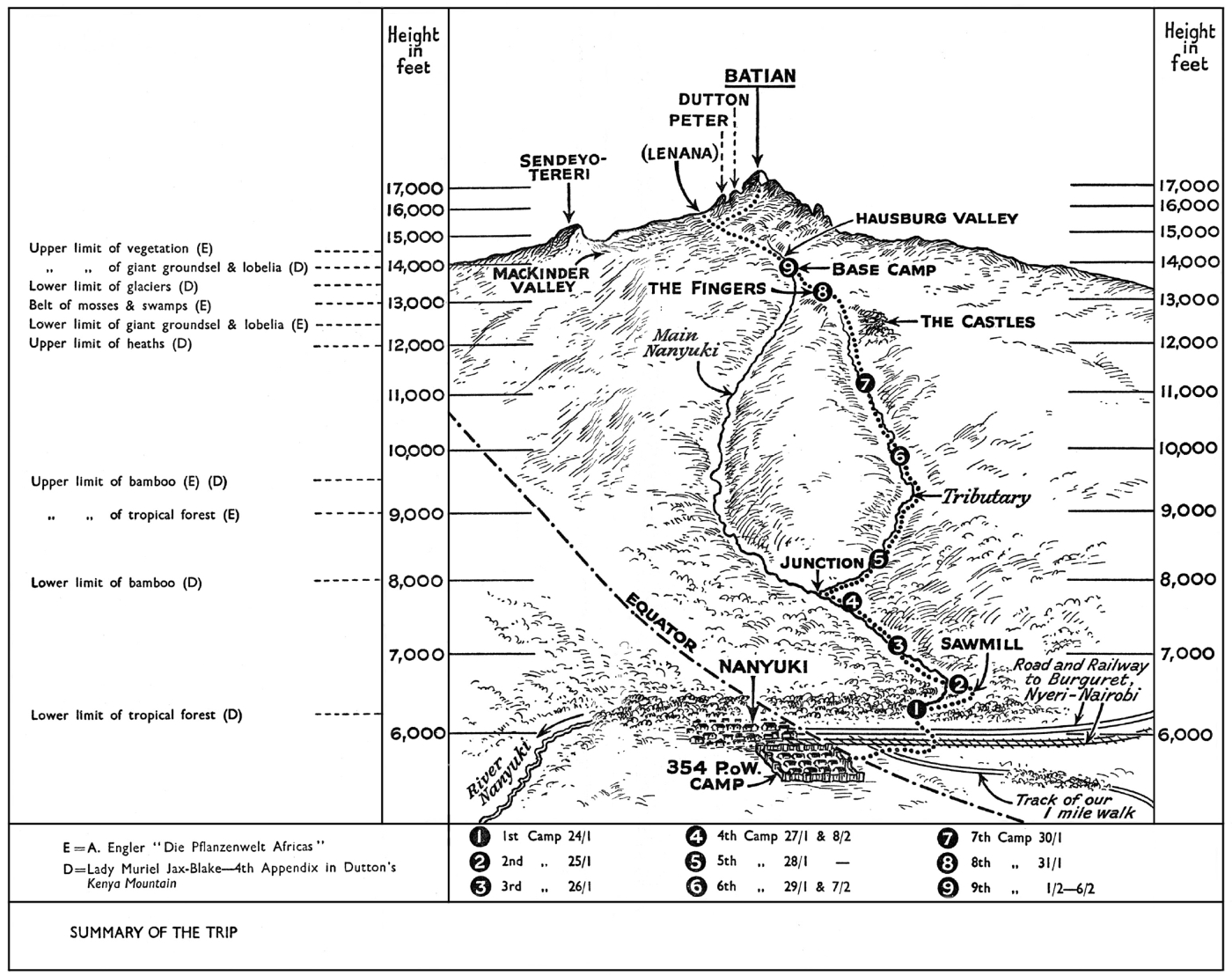

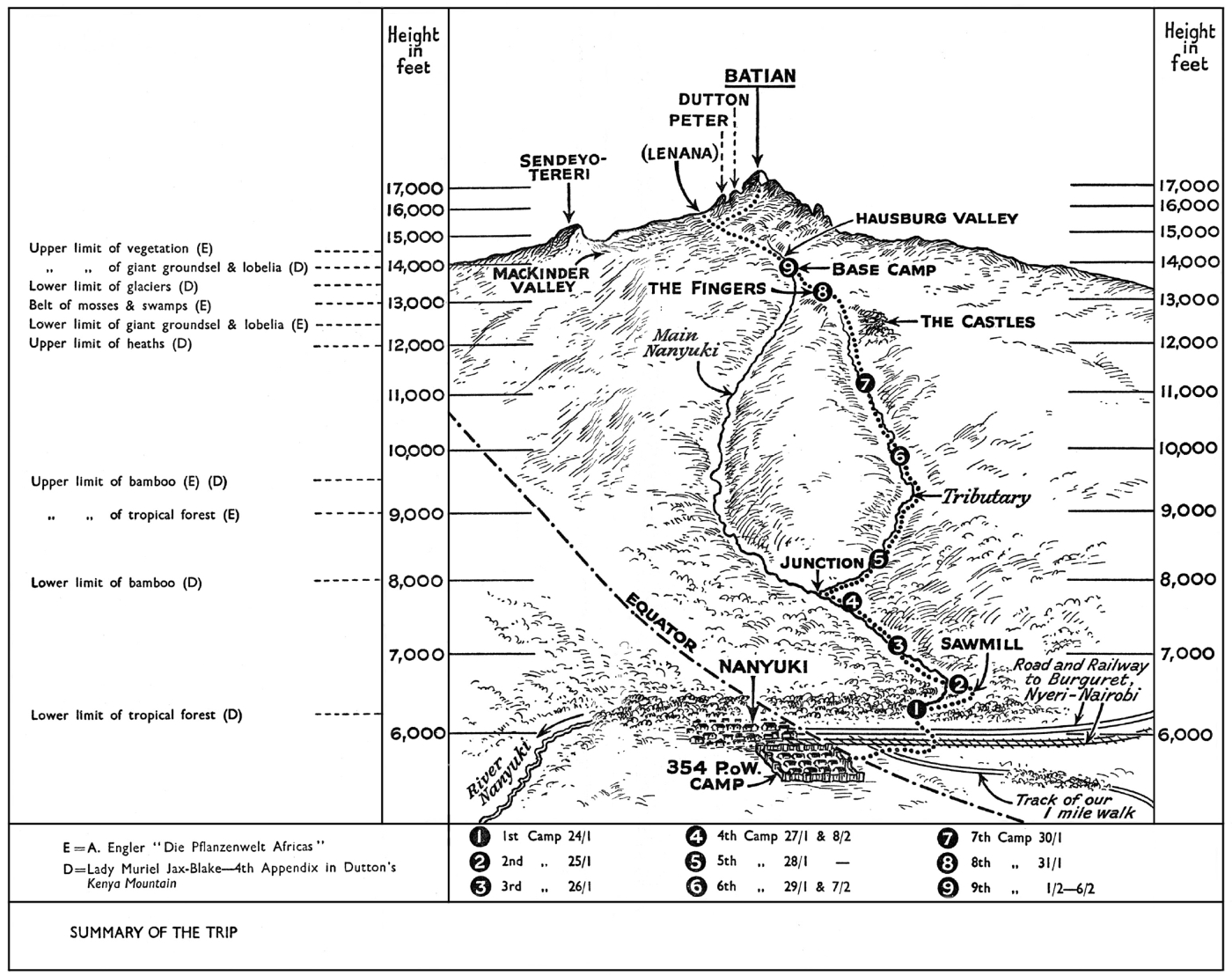

Of life in prisoner of war camps on the Equator, and of the organizing of a mountaineering expedition toward a 17,000-foot peak, despite difficulties over the question of stores and equipment.

After a thirty-six-hour journey, the long train stopped outside a little station, the name of which I could not read from our cattle-truck coach.

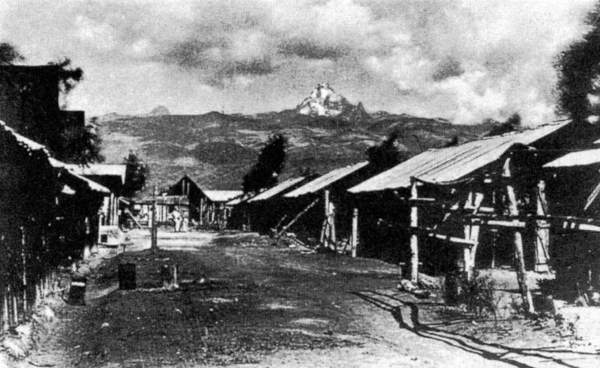

On our left there was a wood of strange thorn trees with smooth green stems; on the right a vast plain where the corrugated iron roofs of hundreds and hundreds of barrack huts shimmered in the midday haze. Between the guard-towers one could make out the barbed wire fence.

The very sight of this encampment tumbled ones heart into ones boots. We stared as though mesmerized, but nobody dared to utter aloud the question each put to himself: Yes, inside there: but for how long?

A dead silence reigned in the wagon while each man gathered up his few belongings. An equally silent column of prisoners from the first wagons was already assembling outside, alongside the rails. We were surely more than a thousand on this train, yet not a word was spoken.

Flies buzzed in the heavy air. In the nearby wood, doves cooed with ironic indifference.

Having traveled in the last wagon, we were the last to start our slow march and in the meantime, the head of the column had covered a good half of the distance between the railway and the camp. In doing so it had raised such a cloud of dust that we were deprived of the depressing sight of our goal.

At last our turn came and we started too, mechanically four by four, heads drooping in the midday heat. The huge snail, slow and dumb, crept forward through the dust cloud as though marching toward infinity.

At the threshold of the camp we were halted and then we entered the gate one by one. It was at last, we had been told, the definitive camp. What a horrible word, definitive!

There was no vegetation to conceal or in any way soften the crudeness of the barbed wire fences. Starkly, almost desperately it seemed, the gallows-like poles supporting the wires reached toward the empty sky.

Why have you woken me up?

Its half-past seven.

But roll-call is at half-past eight. Youve tricked me out of an hour!

Tricked?

If you had left me asleep, I should have avoided one hour of captivity...

A voice from the upper end of the barrack: A four for bridge wanted.

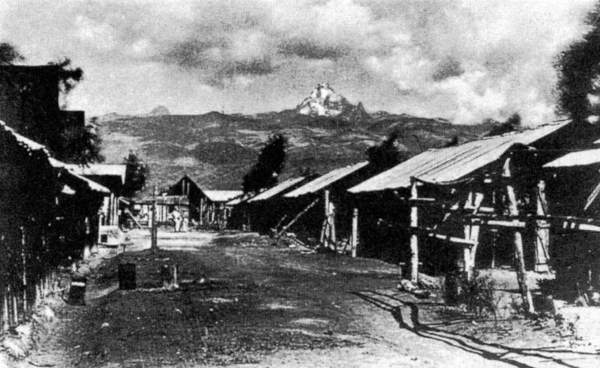

POW Camp 354, Nanyuki, in 1943.

Answer from the far end: For half a loaf of bread you can have me.

The poster on the door of a barrack: Do you want a long and happy captivity? Do as my grandmother did. She lived for 110 years because she minded her own business.

People in prison camps do not live. They only vegetate or as a Russian writer puts it: they live at the level of physiology.

From the Polar Diary of Umberto Cagni, referring to life during the long Arctic night: The spirit gets blunted more and more and the mind of everybody is invaded by an odd indifference for everything not material and not present.

In spite of the communal life each man feels strangely isolated from his fellows.

Every remembrance of the time when we led a less animal-like existence engenders longing, and with it a remote kind of suffering. While forgetting everything and living like a bear one does not feel moral needs which cannot be satisfied.

These truths apply perfectly to our prisoner of war life.

But Admiral Cagni wrote also: I should like to emulate a Spartan and lose all my bad habits. Never in my life shall I have a better opportunity for doing so.

You can never be alone.

You open a letter (if you are lucky enough to get one, once in a blue moon) and ten pairs of eyes gaze at you and ten mouths bombard you with questions: Any news? Good news? Alright? Are they all well?

Thank you very much, you would like to answer, for your kind interest, but couldnt you leave me alone to read, at least now?

You open your suitcase (if you are lucky enough to have one) in order to air your rags or to chase off those black beetles that infest our barracks in legions. Immediately your friends gather round you and exclaim: Look! Youve still got a spare pair of socks! What book is this? May I have a look at this photo? and so on.

You cannot even whistle a tune (if by any chance you get up in a cheerful mood) without hearing another prisoner at the far end of the barrack joining and whistling the same tune.

Next page