Acknowledgements

Thank you to Maya Angelou, Zora Neale Hurston and Alice Walker for opening my eyes; to Nanny for encouraging an early love of the written word; and to Alexandra Pringle, Anna Simpson and the wonderful team at Bloomsbury for encouragement, expertise, patience, support... for believing in me and in this book.

Thanks too to Arabella Stein. And with love to my niece. A special thank you to Wendy for opening up to me about my past, enabling me to shine some light into the dark recesses of my childhood.

Finally, writing this book was, at times, a terrifying experience. Id like to thank everyone who supported me and gave me love and understanding during the writing process.

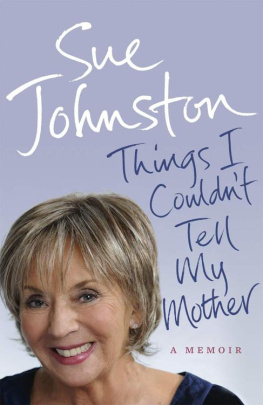

A Note on the Author

Precious Williams is a former contributing editor to Cosmopolitan and her personal essays and celebrity interviews have also appeared in the Telegraph, The Times , the Guardian, Wallpaper, Elle, Marie Claire and the New York Post . She lives in London.

Book One

It cannot be expected that this system of farming would produce any very extraordinary or luxuriant crop.

Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist

Book Three

How simple a thing it seems to me that to know ourselves as we are, we must know our mothers names.

Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers Gardens

Book Two

But I dont want to go among mad people, said Alice.

Oh, you cant help that, said the cat. Were all mad here.

Lewis Carroll,

Alices Adventures in Wonderland

1971

THIS, I AM TOLD, is how it begins.

Its September.

A tall black woman with a foreign accent pulls up to the kerb in a red convertible. She parks on a tree-lined street, on a council estate in rural West Sussex. The stocky, espresso-skinned man next to her keeps twisting round in his seat to gaze at the plump baby girl asleep in a Moses basket on the back seat.

The womans gold bracelets jangle as she switches off the ignition, rolls on an extra layer of lip gloss and adjusts the mirror to pout at her reflection. Unknown to her, net curtains begin to rustle and twitch. White faces peer out. Wondering. Watching.

The woman slams her car door shut. She strides down the little dandelion-choked path to number 52, West Walk, her flat nose tipped towards the setting sun. The man trails several steps behind her. The woman, in her white silk suit, turns and adjusts the lapel of her companions sports jacket.

The front door opens.

The black woman, almost six feet tall, towers over the white woman standing in front of her.

Mrs Taylor? the tall stranger enquires.

Mrs Taylor says she prefers to be called Nanny. The children like it.

Nanny is nearly fifty-seven years old, silver-haired, eyes the colour of clouds on a rainy day. Five feet tall.

Nanny had sent away for the baby in the Moses basket a few days earlier. She had been sending away for African children and looking after them in her home for more than a decade. But when the last two, brothers named Babatunde and Onyeka, were abruptly taken back by their natural parents, Nanny promised herself shed stop. Children coming and going simply caused her too much heartbreak.

Despite that, she still browsed wistfully through the classified ads in the back pages of Nursery World magazine, just to see the latest African children on offer. Thats where she found the infant now on her doorstep. The ad said, attractive baby girl of Nigerian origin. Nanny couldnt resist.

So you must be Mrs... says Nanny, her thin, pale skin blooming with excitement. She does not know how to pronounce the womans name. Im glad you found us all right. Come in, come in.

The woman smiles and stoops slightly in her heels to enter. The man follows her in, clutching the Moses basket.

Please. Call me Lizzy, she says. And this is her. Her names Anita-Precious, she continues, looking absently down at the baby, as if she has just remembered it existed.

Let me have a dekko at her then, says Nanny.

The ten-week-old baby has skin the colour of toffee and a wig-like puff of black tightly curled hair. She lies there curling and uncurling her tiny fists, her round mouth open but unsmiling.

Oh yes, yes. Shes lovely, isnt she, Lizzy? Nanny coos.

Lizzy remains silent. She has a put-out, nauseated look on her face. Like someone whos just trodden in dogs mess while wearing their favourite shoes.

So here I am: the silent, watchful baby in a Moses basket.

Nanny falls in love with me instantly, or at least thats what she tells me once Im old enough to ask about my past.

Gramps, Nannys lovely husband, sits in his wheelchair, smiling rather than talking. His lips no longer work as well as they once did. So when he does speak, his words slide out in a slur. He manages to ask this flawlessly turned-out couple where they come from in Africa. The woman answers for the pair of them. Nigeria . Gramps nods approvingly. Like hes been there.

The sitting room is blue and it coordinates with Nanny, in her blue nylon shirtwaister dress, with the iridescent butterfly brooch on her lapel. Nannys daughter, Wendy, is perched on the end of the blue sofa. Wendy. So slim shes nicknamed Olive Oyl. Long, straight, near-black hair. Skin tanned from the long summer. Eager to hold the brand-new black baby.

Wendys wearing an outfit purple suede fringed coat and flared jeans that Nannys written off as absolutely ridiculous. But despite her hippie gear, Wendys not trying to be a hippie. The most important thing in the world to her is simply becoming a mother. One day.

Wendys fianc, Mick, whose hairs even longer than hers he is here too. His hazel eyes sweep from the baby to the stiff-looking black bloke to the scarily glamorous black lady inches taller than he is who is staring right back at him.

The black couple stays for about an hour that day. The man, whose name turns out to be Rupert, sits there making jittery small-talk. Asking Mick about his job as a caretaker at the local secondary school. Nobody asks who Rupert is whether hes the babys father; whether hes the mothers husband. They presume he is somehow significant since hes there.

My mother carries out an inspection of the three-bedroom council house, briskly appraising the room that will become mine. That done, she curls her sinewy frame into a blue armchair and poses there, calm and elegantly disinterested; not asking anyone many questions, other than how much this placement is going to cost her.

There is a drawn-out conversation about money that day, all in hushed tones, as if the grown-ups are afraid a three-month-old baby could understand their words.

I picture them haggling.

Lizzy quotes the sum she is prepared to pay.

I cant do it for that, Lizzy, Nanny says.

Seven fifty a week then, says Lizzy, offering the lower end of the going-rate for private foster care at that time. It is the most I can afford.

Nanny is calling Lizzys bluff shed have taken me off Lizzys hands for free if necessary.

Later, years later, I will ask Nanny and Wendy and Mick what my mother was like that very first time they met her. What they made of her. Wendy will recall, She was always such a lovely looking woman your mother. Ever so intelligent. So beautifully dressed.

Mick will say, She seemed nice enough, didnt she? Then .

Nanny will say, Very high-faluting. Right from the start. Walked into my house like she bloody well owned it.

My mother will eventually claim, Something about that place, that whole environment, it made my skin crawl.

But this feeling she has doesnt prevent my mother, a reluctant-looking Rupert by her side, returning to Fernmere two or three days later with me in a Moses basket on the back seat of the convertible. And this time, when the pair drives back to their own house in London, the back seat is empty.

Next page