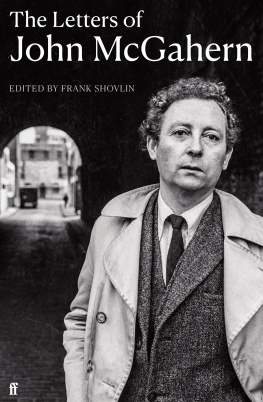

THE LETTERS OF

JOHN McGAHERN

by John McGahern

fiction

THE BARRACKS

THE DARK

NIGHTLINES

THE LEAVETAKING

GETTING THROUGH

THE PORNOGRAPHER

HIGH GROUND

AMONGST WOMEN

THE COLLECTED STORIES

THAT THEY MAY FACE THE RISING SUN

CREATURES OF THE EARTH: NEW AND SELECTED STORIES

non-fiction

MEMOIR

LOVE OF THE WORLD: ESSAYS

(edited by Stanley van der Ziel)

plays

THE POWER OF DARKNESS

THE ROCKINGHAM SHOOT AND OTHER DRAMATIC WRITINGS

(edited by Stanley van der Ziel)

For Madeline McGahern

I think that the difficulty of dealing with letters is that they are never quite honest. Often out of sympathy or diffidence or kindness or affection or self interest we quite rightly hide our true feelings.

JOHN McGAHERN

Letter to Sophia Hillan

19 January 1991

CONTENTS

The Letters

19432006

All published by Faber in London.

The Barracks (1963)

The Dark (1965)

Nightlines (1970)

The Leavetaking (1974)

Getting Through (1978)

The Pornographer (1979)

High Ground (1985)

Amongst Women (1990)

The Power of Darkness (1991)

The Collected Stories (1992)

That They May Face the Rising Sun (2002)

Memoir (2005)

Creatures of the Earth: New and Selected Stories (2006)

Love of the World: Essays, ed. Stanley van der Ziel, int. Declan Kiberd (2009). Abbreviated in footnotes as LOTW.

The Rockingham Shoot and Other Dramatic Writings, ed. and int. Stanley van der Ziel (2018)

I am no good at letters: so writes a twenty-nine-year-old John McGahern to Mary Keelan, an American graduate student whom he had met in Dublin in the summer of 1963 and with whom he had entered a lively epistolary friendship. After confessing this perceived weakness, he explains more about his relationship with the letter as a form: I have written more to you than to anyone ever, theres something unreal about them, theyre neither life nor anything, but its nice for them to come.

And yet, despite this avowed discomfort in the face of letter writing, McGahern would write a host of revealing, forthright and intriguing missives to a variety of people over the course of his life, from close friends to professional contacts, fellow writers and family. That said, it was clear from the outset of this editorial task that I was not dealing with a writer like W. B. Yeats or T. S. Eliot, where multiple volumes would be needed to chronicle the various communications sent out to the world by the author over the years. I dont like writing letters, McGahern tells one correspondent in 1960. So I seldom do which physics nothing.That said, I am aware of no long run of correspondence to which I have not had access and I am confident that the letters reproduced and annotated here give an accurate sense of the writers epistolary life.

McGaherns confession to Keelan about the difficulties of writing a true letter and yet his happiness in receiving same is not surprising, for he liked to read other peoples letters. Among his favourite books were W. B. Yeatss Letters on Poetry to Dorothy Wellesley; Franz Kafkas Letters to Milena; and Rainer Maria Rilkes Letters to a Young Poet. The first of these he gifted to Mary Keelan during that intense friendship of 196364, the last to another friend of Dublins early 1960s, Nuala OFaolain. So fond was McGahern of John Butler Yeatss letters that he undertook to bring forth a new edition in 1999 for both a French and an English audience. The letters, he writes in his lively introduction, have given me pleasure for many years. They can be gossipy, profound, irascible, charming, prejudiced, humorous, intelligent, naive, contradictory, passionate. They are always immediate.

We can say with near certainty that McGahern did not feel about his own letters as Yeats or Dean Swift did about theirs. One never gets the sense when one reads a McGahern letter that it was composed with permanence or posterity in mind. His letters, while often spasmodically beautiful, are not self-conscious works of art. But one might argue that the correspondence, because he is not writing self-consciously, is all the more truthful and revealing. There is a noticeable change in handwriting from the late 1950s cursive, careful script still under the sway of schooldays and teacher training, to the later small, jagged block letters that populate the great majority of his correspondence. As early as 1961, McGaherns penchant for handwriting over typing was irritating his fellow Irish writer John Montague as the two of them exchanged letters on the subject of a proposed anthology of new Irish writing: Your handwriting is so bad that it brings me comfort since mine (which people have always found terrible) couldnt come within an asss roar of yours for incomprehensibility. You also write on both sides of light Only a small number of McGaherns letters are, in fact, typed, and those that are tend to be of a businesslike nature in communication with publishers and agents about contracts or royalties. Very occasionally, in transcribing the work, a word has proved illegible and is marked so by me in square brackets; when McGahern makes an obvious error in leaving out a word, I have inserted that word in square brackets, unless its absence reflects his personal style of speech and prose. I have let oddities of spelling and punctuation stand unremarked. McGahern never felt confident enough to type his own handwritten manuscripts. Prior to the later 1960s and meeting Madeline, he paid for professional transcription of his work. Much of the 100 he won in 1962 as the AE Memorial Award for sections of the still incomplete debut novel that was to become The Barracks in 1963, for instance, was absorbed in paying for half a dozen copies of the work to be typed.

McGahern, contrary to certain received views of him as an isolated gentleman farmer, or what he calls in one note composed towards the end of his life the myth of Farmer John, travelled a good deal and lived at many addresses in Ireland, England, the United States and France. For most letters McGahern supplies an address, for some I have had to rely on postmarks, and for others I have made educated guesses based on dates and contexts. Where the address is not provided, I have used square brackets around what seems the likeliest place of origin. The use of such brackets has also been my practice when estimating dates of composition, although there are a few occasions where the guess has to be as vague as in the case, for instance, for many of Johns letters to his sister Dympna from the late 1950s to early 1960s as just supplying a year rather than a day or a date.

In terms of my footnoting practice, a short biography of each correspondent is supplied for the first letter or email. Where possible, these biographies include year of birth and, where applicable, year of death. When a question arises in a letter that appears not to be addressed in the footnote, the reader can assume that it was not possible to supply an answer despite my best efforts. The only alternative to this method would have been to footnote unknown whenever I had failed to track down fully the source of the piece of information or the answer to some question that arose within the letter. Very occasionally I have chosen to do this if I thought it helpful to the reader. I have kept editorial comment especially as it relates to the interplay between the life and the work to a minimum. So, for instance, I have not found it necessary to comment on the ways in which McGaherns December 1957 letter to Tony Swift breaks into second person singular narrative to describe first person action, just as occurs at length in

Next page