Interior view, National Gallery of Ireland, c. 1929

Photo National Gallery of Ireland

About the Editor

Janet McLean is Curator of European Art, 18501950, at the National Gallery of Ireland. She grew up in Co. Down and was educated at Trinity College Dublin and the Courtauld Institute of Art. She has previously been a curator at the Watts Gallery, Compton, the Palace of Westminster and the Royal Academy of Arts, London.

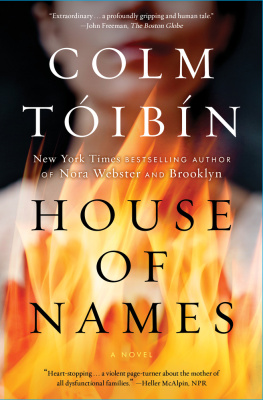

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Rendez-vous with Art

The Book of Kells

The Essential Samuel Beckett:

An Illustrated Biography

James Joyces Dublin:

A Topographical Guide to the Dublin of Ulysses

W. B. Yeats

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

The National Gallery of Ireland opened its doors to the public for the first time in 1864. It then displayed 112 paintings. Today the collection has grown to comprise over 15,000 works of art, dating from the thirteenth century to the present day. To mark the 150th anniversary of the gallery, fifty-six Irish writers have contributed essays, stories and poems to Lines of Vision, an anthology inspired by its rich collection. Their texts span a wide range of genres to give unique perspectives into the pictures they have chosen.

The writers have selected diverse works from across the collection. They include treasured paintings by masters such as Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Poussin and Velzquez; works by Irish artists such as Jack B. Yeats, John Lavery and Paul Henry; and modern European pictures by Claude Monet, Pierre Bonnard and Gabriele Mnter. This creative collaboration invites us to look at the National Gallery of Ireland and its wonderful collection in new and intriguing ways.

SEAN RAINBIRD, DIRECTOR, NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND

When the National Gallery of Ireland opened on 30 January 1864, among the guests gathered for the official ceremony was the newly knighted Sir William Wilde. While it might be considered fanciful to imagine that his nine-year-old son, Oscar, watched the grand occasion from the windows of their family home on Merrion Square, what cannot be doubted is that, from that day forward, the National Gallery has come to figure prominently in Irish literary life.

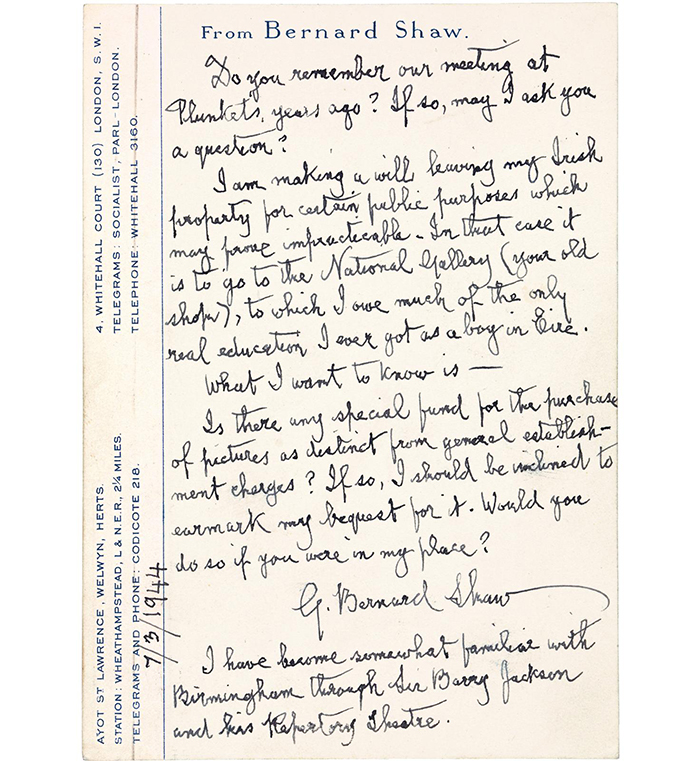

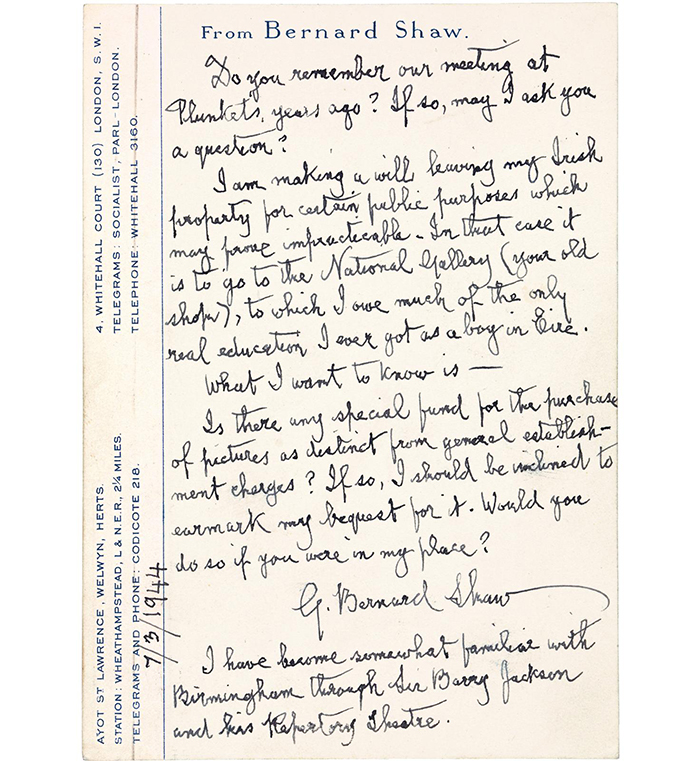

George Bernard Shaw had been living in England for almost seventy years when, in 1944, he wrote to Thomas Bodkin, a former director, saying that he owed the gallery much of the only real education I ever got as a boy in Eire. He subsequently bequeathed one third of the royalties from his work to fund new acquisitions. These have included Roderic OConors La Jeune Bretonne and Jack B. Yeatss Grief; paintings which have in turn, inspired the contributions of Dermot Bolger and Carlo Gbler in this volume. W. B. Yeats belonged to a family of artists and studied at Dublins Metropolitan School of Art before embarking on the path of poetry. He remained interested in art throughout his life and joined the gallerys Board of Governors in the 1920s. Paintings by his father, John, and brother, Jack, are included in this book.

Postcard from George Bernard Shaw to Thomas Bodkin, 7 March 1944

Photo National Gallery of Ireland

The writer and poet James Stephens was the gallery registrar from 1919 to 1924. During this period he published several books, including the popular Irish Fairy Tales (1920), illustrated by Arthur Rackham. Stephenss successor, Brinsley MacNamara, took up the post having been exiled from his hometown in Co. Westmeath where his novel Valley of the Squinting Windows (1918) had been received with hostility. He continued to write fiction and plays up until his retirement in 1960. The respected poet and critic Thomas MacGreevy was the gallerys director from 1950 to 1963. Samuel Beckett, an old friend of MacGreevy, had come to know the gallery as a young man and was particularly keen on its early Italian paintings and works by Dutch and Flemish Masters. It was MacGreevy who introduced Beckett to Jack B. Yeats, an artist whose work they both deeply admired and which continues to resonate with writers today.

Lines of Vision brings together new work by Irish writers, inspired by the National Gallery of Ireland and its collection. Contributors were invited to select pictures as setting-off points for poems, stories and essays. Each has embraced the undertaking with unfailing enthusiasm and tremendous generosity of spirit.

Behind the scenes, the picture selection process was a delightfully idiosyncratic one. A number of writers visited the gallery with an idea but not a picture in mind, others perused its stores, a few gave approval to prompted pairings, while most chose works of art that they had long loved and even lived with as postcards propped on mantelpieces or tacked to study walls. The writers reasons for choosing pictures are as diverse as those they chose. Pictures have been used as stimuli for dormant stories waiting to be told. Pictures have teased out long-held observations and nudged them into form and focus. Pictures have become the fabric on which remembrances have been pinned like precious brooches. Pictures have been reimagined, their details magnified and presented in new lights.

For many years the National Gallery was one of the few secular spaces where art could be seen in Ireland. Indeed it is quite possible that for many of the writers in this book, their initial encounters with art were with religious imagery seen in churches and schools; altarpieces, stained-glass windows, shrines, Stations of the Cross, Sacred Heart prints. The interweaving of art, poetry, stories and spirituality comes almost as second-nature to Irish writers. While it is perhaps unsurprising that many find an affinity with religious scenes and subject matter, it is certainly intriguing that several have been drawn to images of ascetic saints. St Mary Magdalene, St Jerome, St Francis and St Onuphrius their pictured lives of austere and contemplative solitude bear distinct parallels with the garret-occupation of writing.

Galleries are places where few questions are asked or expectations are made. Quite often they are places of retreat for those who have time to pass or places of refuge for those who feel they dont fit in. The idea of art as a bolthole from uncomfortable realities in childhood, adolescence and adulthood is a reassuring and recurrent one in this collection of writing. Galleries invite their visitors to engage in discreet acts of intimacy. There is a silence and a stillness implied in looking at art. Writers are perhaps more at ease with the practice of seeing slowly than most.

Many writers have found in paintings fragile bridges by which to bring lost loved ones closer into view. Sebastian Barry movingly remembers his artist grandfather; Bernard Farrell and Martin Malone the quiet dignity of their fathers; Eilan N Chuilleanin her sister, a violinist; Michael Longley his friend Gerard Dillon; and Jennifer Johnston her hospitable godmother. Quite remarkably, Eva Bourke reflects upon a portrait of her ancestor, Anton Hundertpfundt, Master of the Mint to the Bavarian court in the sixteenth century.

Pictures in public collections might be looked upon as meeting points. They hang suspended on their fixings while people pause, and then, like time, pass by. When looking at pictures we see what others saw before us and what others after us will see. There is a poignant beauty to be found in these invisible path-crossings. Shortly after visiting the National Gallery of Ireland in 1926, Louis MacNeice wrote Poussin inspired by the painting

Next page