Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

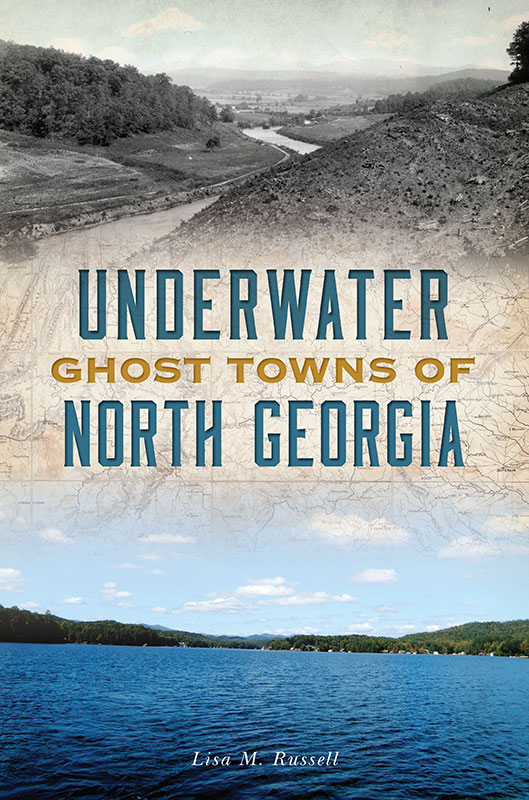

Copyright 2018 by Lisa M. Russell

All rights reserved

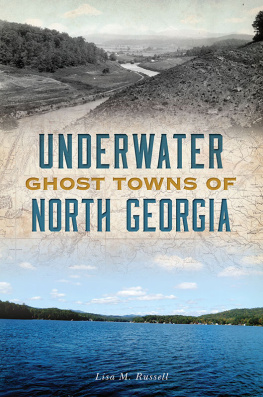

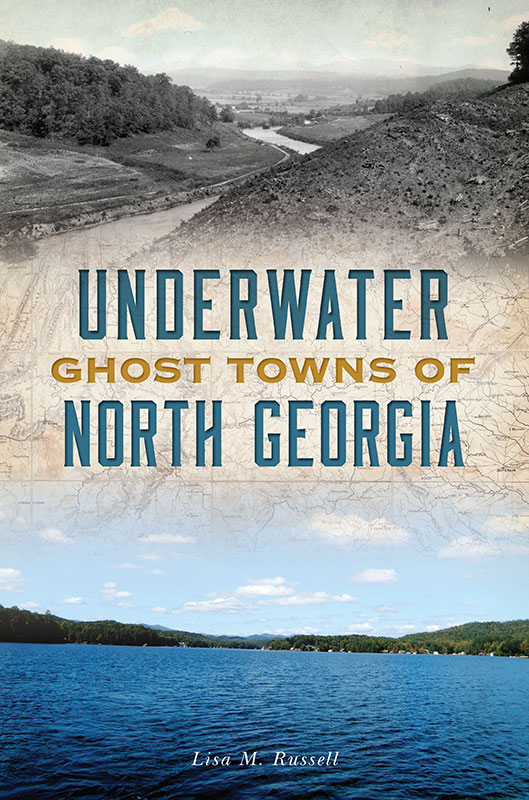

Front cover, top: Map. Library of Congress; bottom: pseabolt, via Wikimedia Commons.

First published 2018

e-book edition 2018

ISBN 978.1.43966.501.5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018940075

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.984.7

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For Josie Brooke Russell May your precious heart be as free as the wild rivers of North Georgia

In writing Underwater Ghost Towns of North Georgia, Lisa Russell shares her love of uncovering history, connecting land and people with legacy. Russell closes with a vision of a future that would not attempt to ignore past mistakes, nor rewrite history, but challenges us to look toward new solutions that would leave our wild rivers free. Jackie Cushman

Just before the impounding of Carters Lake, a paddler making his way down the Coosawattee River saw an old-timer fishing on the bank. They biting today? the paddler asked. I dont know yet, the fisherman replied. But theyre messing up a mighty pretty river. Georgia lost many pretty rivers in the twentieth century. Were familiar with the touted benefits: flood control, water storage, and recreation. In Underwater Ghost Towns of North Georgia, Lisa Russell shows us some of what we lost: beautiful rivers, tranquil valleys and rich natural and human history. Dan Roper, editor, Georgia Backroads magazine

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Once upon a time, the rivers were wild. Communities built up around the unruly North Georgia waterways while farmers eked out a livelihood in fertile river bottom lands composed of red chocolate soil. Described by explorers and poets like Bartram, McPhee, Reese, Dickey and Lanier, the rivers seemed for a moment mythical and sensuous. This book was not drafted as an environmentalist argument but rather a review of drowned towns. The goal was to surface ghost towns and remnants of places ravaged by the impoundment. This work has been an unexpected adventure with swift switchbacks and undertones of ambiguity. The journey caused a question to surface. What if ?

What if the rivers continued to flow? What if we developed alternative ways to harness electricity? Was the damage to terrain and community worth it? While the impoundment destroyed towns, the same dams prevented devastating floods in Rome and Gainesville. Artists try to capture place. Place is not only a physical description, it also involves cultural and psychological elements. These stories attempt to portray a place in the life and words of those who lived through the radical changes to their mountain land. Ponder the past as we visit the lakes.

THE POETRY

In the 1700s, William Bartram had to delay his trip back home to Philadelphia. He scribbled in his diary that this circumstance allowed me time and opportunity to continue my excursions in this land of flowers.

Bartram, a botanist, explored North Georgia and recorded the beauty of the rivers and the flora on the banks with poetic words. His records left a snapshot of a distant memory.

After the Civil War, Sidney Lanier traveled the hills of North Georgia and composed Song of the Chattahoochee. He drew attention to the regions simplistic beauty, reflecting on a place that no longer exists. This was Laniers favorite poem:

THE SONG OF THE CHATTAHOOCHEE

Out of the hills of Habersham,

Down the valleys of Hall,

I hurry amain to reach the plain,

Run the rapid and leap the fall,

Split at the rock and together again,

Accept my bed, or narrow or wide,

And flee from folly on every side

With a lovers pain to attain the plain

Far from the hills of Habersham,

Far from the valleys of Hall.

All down the hills of Habersham,

All through the valleys of Hall,

The rushes cried Abide, abide,

The wilful waterweeds held me thrall,

The laving laurel turned my tide,

The ferns and the fondling grass said Stay,

The dewberry dipped for to work delay,

And the little reeds sighed Abide, abide,

Here in the hills of Habersham,

Here in the valleys of Hall.

High oer the hills of Habersham,

Veiling the valleys of Hall,

The hickory told me manifold

Fair tales of shade, the poplar tall

Wrought me her shadowy self to hold,

The chestnut, the oak, the walnut, the pine,

Overleaning with flickering meaning and sign,

Said, Pass not, so cold, these manifold

Deep shades of the hills of Habersham,

These glades in the valleys of Hall.

And oft in the hills of Habersham,

And oft in the valleys of Hall,

The white quartz shone, and the smooth brook-stone

Did bar me of passage with friendly brawl,

And many a luminous jewel lone

Crystals clear or a-cloud with mist,

Ruby, garnet, and amethyst-

Made lures with the lights of streaming stone

In the clefts of the hills of Habersham,

In the beds of the valleys of Hall.

But oh, not the hills of Habersham,

And oh, not the valleys of Hall

Avail: I am fain for to water the plain.

Downward the voices of Duty call-

Downward, to toil and be mixed with the main,

The dry fields burn, and the mills are to turn,

And a myriad flowers mortally yearn,

And the lordly main from beyond the plain

In 1953, the valleys of Hall would become Lake Sidney Lanier.

THE LEGACY

Looking at the North Georgia lakes requires looking in the past through the eyes of those who walked the land. The aim is to tell the peoples story. To look at remaining scars on the mountain community.

Famed writer John McPhee took a wild trip in the 1970s across Georgia. He experienced back roads and the Chattahoochee River:

The Chattahoochee rises off the slopes of the Brasstown Bald, Georgias highest mountain, seven miles from North Carolina, and flows to Florida, where its name changes at the frontier. It is thereafter called the Apalachicola. In all its four hundred Georgia miles, what seems most remarkable about this river is that it flows into Atlanta nearly wild. Through a series of rapids between high forested bluffs, it enters the city clear and clean. From parts of the Chattahoochee within the city of Atlanta, no structures are visiblejust water, sky, and woodland. The circumstance is nostalgic, archaic, and unimaginable.Atlanta deserves little credit for the clear Chattahoochee, though, because the Chattahoochee is killed before it leaves the city.

On this same trek across Georgia, McPhee took a canoe trip with then governor Jimmy Carter. Carter said while on the Chattahoochee in 1973, We are lucky here in Georgia that the environment thing has risen nationally, because Georgia is less developed than some states and still has much to save.

Next page