COME from the SHADOWS

the LONG and LONELY

STRUGGLE for PEACE in

AFGHANISTAN

TERRY GLAVIN

COME FROM THE

SHADOWS

Douglas & McIntyre

D&M PUBLISHERS INC.

Vancouver/Toronto/Berkeley

Copyright 2011 by Terry Glavin

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Douglas & McIntyre

An imprint of D&M Publishers Inc.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver BC Canada V5T 4S7

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-55365-782-8 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-55365-783-5 (ebook)

Editing by Barbara Pulling

Copyediting by Lara Kordic

Jacket design by Naomi MacDougall

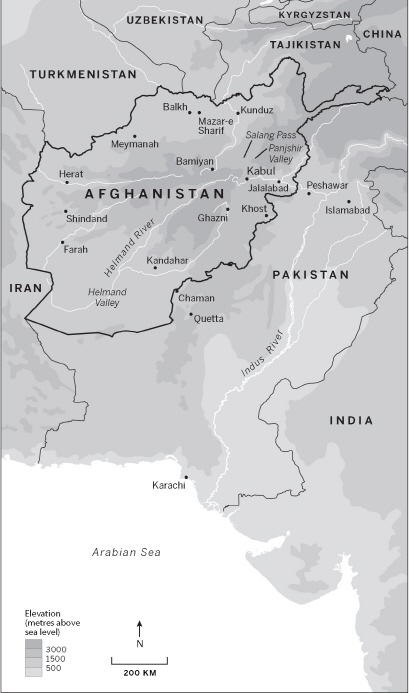

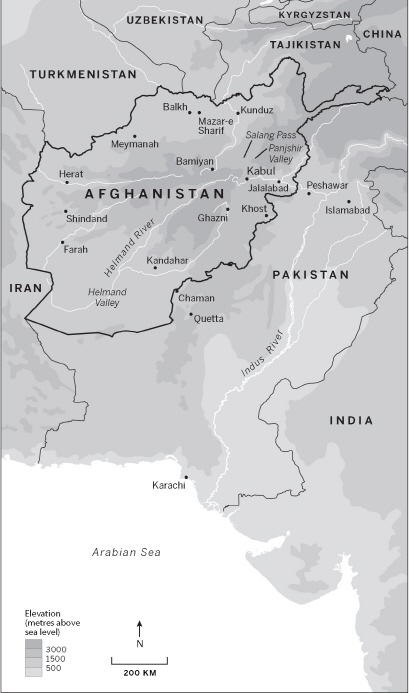

Map by Eric Leinberger

Jacket photograph: Veronique de Viguerie/Getty Images.

The photo depicts a Kuchi woman of the Niazi tribe, Kandahar, 2004.

Distributed in the U.S. by Publishers Group West

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

Oh, the wind, the wind is blowing,

through the graves the wind is blowing,

freedom soon will come;

then well come from the shadows.

The Partisan, Leonard Cohen, 1969

The wind blows through the graves,

freedom will return.

We will be forgotten. We will return to the shadows.

Le Complainte du Partisan, Emmanuel dAstier de la Vigerie and Anna Marly, 1943

CONTENTS

Indifference to objective truth is encouraged by the sealing-off of onepart of the world from another, which makes it harder and harderto discover what is actually happening. There can often be a genuinedoubt about the most enormous events. For example, it is impossible tocalculate within millions, perhaps even tens of millions, the number ofdeaths caused by the present war. The calamities that are constantlybeing reportedbattles, massacres, famines, revolutionstend toinspire in the average person a feeling of unreality. One has no wayof verifying the facts, one is not even fully certain that they havehappened, and one is always presented with totally different interpretationsfrom different sources... Probably the truth is discoverable, butthe facts will be so dishonestly set forth in almost any newspaper thatthe ordinary reader can be forgiven either for swallowing lies or failingto form an opinion. The general uncertainty as to what is really happeningmakes it easier to cling to lunatic beliefs.

from George Orwells Notes on Nationalism, in Polemic, October 1945

T HE LITTLE CITY of Daste Barchi is not on any official map, and there are no road signs to tell you how to find it. To get there, you look for a particular dirt track that seems to come out of nowhere from behind the bombed-out hulk of the Duralaman Palace on the outskirts of Kabul. You follow the track into the foothills of the snow-covered Paghman Mountains. It becomes a rutted, westward-twisting dirt road for about an hour or so, and then it begins to weave through Jabarhan, a teeming place of tiny, flat-roofed mud brick houses and narrow alleyways alive with children and flocks of sheep and chickens. Just when you think youre lost, and the road could not get any narrower, you are in Daste Barchi.

Daste Barchi means Barchi Desert. It is not a desert. It is a city. Perhaps as many as a million people live in Daste Barchi and its environs. The people are mainly Hazaras, from Afghanistans Shia minority. These are the people you see at first light down in Kabul, sweeping the streets and pulling handcarts heavy with cauliflowers and pomegranates. Theyre the day labourers, the house servants, the people who take out Kabuls washing. Without them, Kabul would come apart. The area encompassing Daste Barchi lies within an administrative unit called Police District 13. Apart from what some people manage to procure from diesel generators, there is no electricity. There is no running water. The residents of Police District 13 are classified as Internally Displaced Persons. Daste Barchi does not officially exist.

It is in places like Daste Barchi that the terrain I set out to explore in this book appears in sharp relief. This is the landscape between the Afghanistan that animates debates in Western democracies and the places outside the wire, as the entire country is often bizarrely and euphemistically described. Having spent fifteen years of my life working for daily newspapers, Im well acquainted with the distance that can exist between the way the world really is and the way accounts of that world enliven the public imagination. But between the real Afghanistan and the imaginary one, there is a chasm. I travelled to Kabul and Kandahar in 2008, and to Kandahar again in 2009. In 2010 I was back in Afghanistan twice, with Abdulrahim Parwani, a friend from Canada, a colleague and fellow journalist whose story will figure prominently in this book. We went to Daste Barchi in the spring of 2010 to learn about a story that casts light down into that chasm. It involves an event that had come to be called the Battle of Marefat High School.

In the activist polemics of North Americas wealthy, privileged students, Afghanistan shows up as a project of American imperialism, an effort by us in the capitalist West to impose our hegemonic, democratic values on them. It brooks only one response: troops out. At Marefat High School, in a cold and poorly lit classroom, the students have decorated the walls with oil paintings of some of the great champions of values that do not draw such distinctions between them and us. The students painted the portraits themselves: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Ren Descartes, Rosa Parks, Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, Ali Akbar Dehkhoda, Immanuel Kant, Abraham Lincoln, Voltaire, Baruch Spinoza and Jawaharlal Nehru. This may seem a mere incongruity, a touching detail, a small matter. It isnt. Its not just a mark of the distance between the imaginary Afghanistan and the real one, either. Its what the Battle of Marefat High School was all about.

Marefat High School is supported almost entirely by the poor of Daste Barchi. The schools focus is on humanism and civic education. The school is accredited by the Afghan government, but it has had a rocky relationship with the education ministry, owing to the students demands for fully co-educational classes. The roughly three thousand students who attend the school are encouraged to use the Internet, set up personal web pages and communicate with the outside world. Elected class councils and discipline councils allow students to evaluate teachers, tutor one another and manage their own affairs, right down to the amount of the fines levied for overdue library books. The school is governed by a board of trustees elected by parents, students and teachers. There is also an independent student parliament. The idea is that these forms of self-government will encourage students to get into the habit of taking charge of their own lives. This requires practice, hard work and a lot of give and take. It is the art that is known in the West as democracy.

Next page