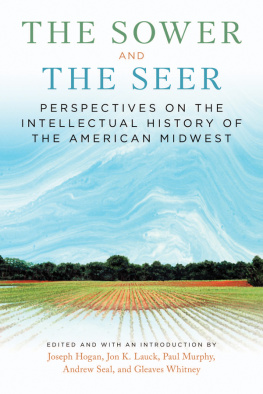

The Sower and the Seer

The Sower and the Seer

Perspectives on the Intellectual History of the American Midwest

Edited by

Joseph Hogan, Jon K. Lauck, Paul Murphy, Andrew Seal, and Gleaves Whitney

WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

The Wisconsin Historical Society helps people connect to the past by collecting, preserving, and sharing stories. Founded in 1846, the Society is one of the nations finest historical institutions.

Join the Wisconsin Historical Society: wisconsinhistory.org/membership

2021 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin

E-book edition 2021

For permission to reuse material from The Sower and the Seer: Perspectives on the Intellectual History of the American Midwest (ISBN 978-0-87020-948-2; e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-949-9), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

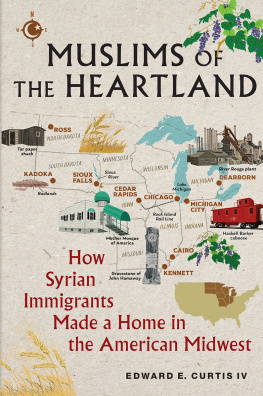

Front cover image: Crop Rows by Shane McAdams, photographed by Tom Bamberger

Cover design and typesetting by Tom Heffron

25 24 23 22 21 1 2 3 4 5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hogan, Joseph, 1992 editor. | Lauck, Jon, 1971 editor. | Murphy, Paul V. (Paul Vincent), 1966 editor. | Seal, Andrew, 1984 editor. | Whitney, Gleaves, editor.

Title: The sower and the seer : perspectives on the intellectual history of the American Midwest / edited by Joseph Hogan, Jon K. Lauck, Paul Murphy, Andrew Seal and Gleaves Whitney.

Description: [Madison, Wisconsin] : Wisconsin Historical Society Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020028337 (print) | LCCN 2020028338 (ebook) | ISBN 9780870209482 (paperback) | ISBN 9780870209499 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: IntellectualsMiddle WestHistory. | Middle WestIntellectual life. | Middle WestHistory. | Middle WestCivilization.

Classification: LCC F351 .S69 2020 (print) | LCC F351 (ebook) | DDC 977dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020028337

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020028338

To the memory of John E. Miller, Midwestern intellectual

Contents

Sower and Seer

Liberty Hyde Bailey

Full patiently the sower walked on his acres deep and clean

And dropped his handfuls one by one for the harvest full and green,

Full punctually he tilled his lands and groomed his sleek-fed kine

And frugally at sunrise and eve he dressed his yard and vine;

When days were fair he thrust his plow and compelled his clicking drills

And when wilding storms were loosed and raw he sped his barn-snug mills;

And day by day the sun rose and set upon his circling hills.

Full forwardly the seer stood on the rim of circling hills

Where trees were bent on the jagged cliffs and eagles dropped their quills

With shimmering farm-lands far below and spires of roof-flecked vills;

Full eastwardly and westwardly all the sweeping earth lay prone

And upwardly the fleecing clouds in a bondless sunlight shone;

All things beneath and all above were in webs of vision spun

Till every part was as the whole and all the whole was one.

The sower and the seer each

Down lifes unending way

Held fast his single speech

And lived his seprate day.

For one man cast his seed

And sped the coupled hours,

He stored his treasured meed

And plucked his garden flowrs.

And one man stood alone

Where all the world was his,

All things that men have known

And all that was and is.

Alack, all ye that sow

And alack, ye that see,

No longer shall ye go

All seprate and unfree:

For one shall make far quests,

The other side him fare

And come back from the crests

With star-winds in his hair.

Liberty Hyde Bailey, Sower and Seer, in Wind and Weather, (New York: Scribner, 1916), 127129.

M idwestern seers, as Liberty Hyde Bailey calls them, are the interest of this collection. They are the writers, thinkers, intellectuals produced by the Midwest. And as Bailey shows, their work cannot be separated from their region. The region is responsible for them, and they for their region, as the sower is responsible for the land, and the land for the sower. The region offers a harvest of knowledge; intellectual and imaginative vision is reaped from it. The region gives its seers perspective, a vantage from which to see full eastwardly and westwardly. By giving them roots, it sets them free.

And yet, since at least the mid-twentieth century, the dominant assumption about the Midwest, the story often told about it, is that its a place one leavesif, that is, one wants to live, to experience, to think, to be free. American literature and criticism has, for years, celebrated a kind of regional brain drain. The revolt from the village thesis, first articulated in 1920 by Carl Van Doren in The Nation, applauds a certain trend in American writing that opposed the pastoral image of the middle-American small town. Van Doren admired, for instance, Edgar Lee Masterss Spoon River Anthology (1915) and Sherwood Andersons Winesburg, Ohio (1919) for their embrace of a formula of revolt against provincialism. The idea was, and remains, that the old vision of the wholesome small town ought to be undone; to rebel against it is to rebel against provincialism itself.

F. Scott Fitzgeralds The Great Gatsby partly endorses, but in an important sense critiques and improves, this thesis. At the beginning, the Minnesotan Nick Carraway determines to leave the Midwestthe ragged edge of the universeto go to New York, where he has the high intention of reading many books: I was rather literary in college... and now I was going to bring back all such things into my life and become again that most limited of all specialists, the well-rounded man. To live on the East Coast, Carraway intuits, is to become capable of gaining

Despite Gatsbys nuanced portrait of the Midwest and the East Coast, Van Dorens revolt from the village thesis has largely endured. With it has emerged the common assumption that the nations interior states are excellent seedbeds for the germination of native geniusesfrom T. S. Eliot to Jonathan Franzenbut a wasteland for their further growth. This trope has made its way into novels, films, and television. It is as recent as the HBO show Girls, whose main character, Hannah Horvath, was raised in East Lansing, Michigan, but moved, after college, to Brooklyn. In her Midwestern parents hotel room in midtown, Horvath announces that she thinks she might be the voice of my generation, or at least a voice of a generation. Indeed, to leave the Midwest for the coasts is to ditch provincialism in favor of something like cosmopolitanism. Or perhaps it is to embrace the default, the thing itself: to think in the Midwest is to think regionally; to think on the East Coast is simply to think. It is to become capable of participating in a nonregional, nonprovincial great conversation; it is, regardless of region, to become capable of speaking for ones generation. Or