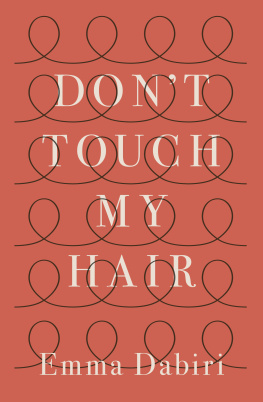

Emma Dabiri

DONT TOUCH MY HAIR

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2019

Copyright Emma Dabiri, 2019

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-0-141-98629-6

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

In honour of all the black brilliance and beauty,

squandered and diminished

yet never extinguished.

1

Its Only Hair

YOUNG, IRISH AND BLACK

It is not from my mouth

It is not from the mouth of A

Who gave it to B

Who gave it to C

Who gave it to D

Who gave it to E

Who gave it to F

Who gave it to me.

That it be better in my mouth

Than in the mouth of my ancestors.

(West African poem)

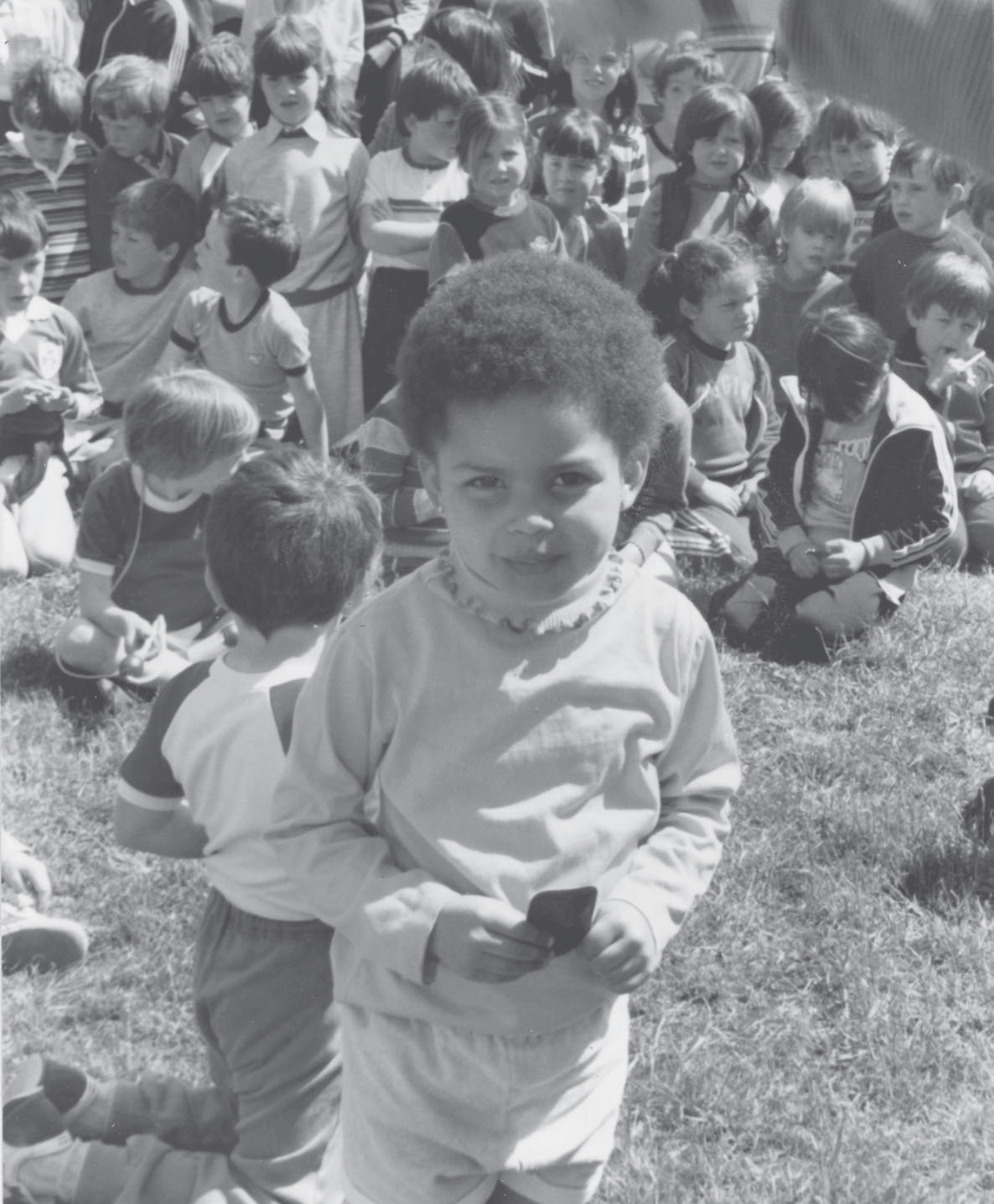

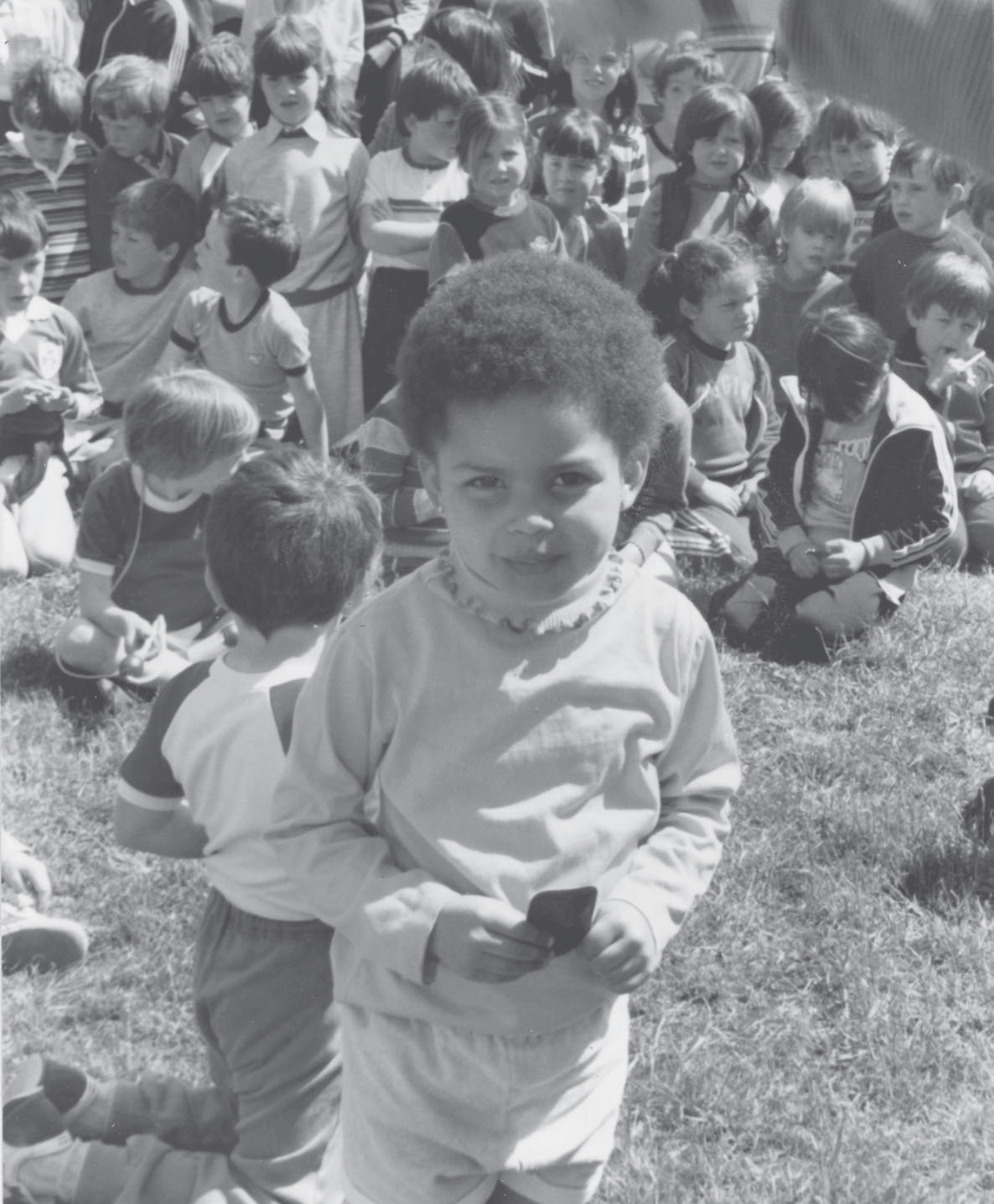

The year I turned eight, the consumption of Christs body and blood became imminent. After months of deliberation, extravagant miniature bridal dresses had been bought; lace, satin and net hung expectantly in wardrobes. The communion money, which could quite reasonably be expected to stretch into the hundreds a veritable fortune in 1980s inner-city Dublin was the hot promise occupying everyones thoughts. After months of slaving over the catechism, of hard work and dutiful preparation, my peers were ready to make their first Holy Communion.

No catechism for this badman, though. I had elected not to take the sacrament. Young Emmas contribution, having reached the age of reason, was instead the production of a spiffy little anti-slavery pamphlet called Break the Chains. The length of a copy-book, it was based on the story of Olaudah Equiano, the eighteenth-century abolitionist. The conclusion, I remember, attempted to locate the contemporary conditions of Black America in the brutal experiences Africans had endured in that land and sought to suggest solutions. Hence the title. Nice and light. Standard childhood fare.

While I wasnt particularly praised for my efforts, I certainly wasnt forced to join in with the other children either. With hindsight, this is telling, if unsurprising. There was always the insistence that, despite my being born in Ireland and having an Irish mother whose maternal ancestry stretches back into Irish pre-history, I wasnt really Irish. I was frequently singled out for special attention. I seemed to be a firm favourite of nuns, particularly those who had been missionaries in Africa. I remember on one occasion being apprehended outside the Bird Flanagan pub in Rialto and presented with a Miraculous Medal by a concerned nun who wished to bestow the grace of the Virgin Mary on my little brown body. It was not the only time I was presented with one of these I seemed to be quite the miraculous magnet! And I remember visiting a friends elderly great-aunt another nun whose watery eyes refocused then blazed upon sighting me. I spent years in Nigeria, she thundered, before proceeding to pull my lips back over my teeth, because Your people have such beautiful teeth. Given that this rather intimate exchange occurred before even the most basic of introductions, one might think it, at the very least, rude.

So yeah, I had a complicated relationship with the world I lived in. And I think the fact that I embarked on the Equiano project was most likely interpreted as just the sort of weird shit that a foreigner, a blackie might do. I mean, What dye expect from the likes of them, like?

Thinking about Equiano now, my decision does seem radical. I cant remember precisely what my motivation was, but my childhood was often characterized by unusual choices and interests, informed by a strong sense that my impulse to tell black stories originated from a source that pre-dated my birth: It is not from my mouth

Though it might sound peculiar and it certainly felt strange to me: I felt intuitively that I had a working relationship with the past and with my forebears. It was as though the past happened to be particularly foregrounded in my present. Of course, I couldnt articulate this, even to myself, and had I been able to, I would most likely have elected not to. As a child, I was considered strange enough. No need for further ammunition. It was only when, years later, I went to university and studied African cultures that I learned about the centrality of ancestral veneration, that ancestral spirits were intentionally invoked. On my paternal side I am Yoruba. The Yoruba are the largest ethnic group in south-western Nigeria and one of the third biggest in Nigeria, Africas most populous country. Many Yoruba were sold into slavery, particularly during the nineteenth century. As a result of this relatively recent, wide-scale movement, many Yoruba beliefs, practices and customs can be identified to this day throughout the New World. During the 1980s and 1990s a more recent Yoruba diaspora was created, as Nigerians fled their tragically failing economy to migrate to countries such as the US and the UK.

One result of colonialism was a disregard for many Yoruba beliefs; therefore it was only at university that I learned that traditional Yoruba concepts of time were cyclical, and of the belief that the past is not necessarily dispensed with but is in fact in dialogue with the future.

I discovered that Yoruba names such as Babatunde (Father comes again) and Yetunde (Mother comes again) are so common because of an indigenous belief in the transmigration of the soul. This invocation of the past, like the Ghanaian philosophical concept of Sankofa (which urges us to take from the past to design a better future), does not limit progress or place emphasis on doing things the old way. On the contrary, improvement is the objective. The urge to ensure that the mine be better in my mouth / Than in the mouth of my ancestors. It is believed that our successes are our great-greats successes too. Finally, I could locate my experiences in a belief system where they made perfect sense.

Received Western wisdom routinely denigrates African history. The attitude was summed up by the esteemed historian Hugh Trevor-Roper in his famous 1963 address at Sussex University, which was broadcast on national television, as well as being published both in a popular periodical and as a book:

Perhaps, in the future, there will be some African history to teach. But at present there is none, or very little: there is only the history of the Europeans in Africa. The rest is largely darkness, like the history of pre-European, pre-Columbian America. And darkness is not a subject for history.