Living Out

Gay and Lesbian Autobiographies

David Bergman, Joan Larkin, and Raphael Kadushin

Founding Editors

Publication of this book has been made possible, in part, through support from the Brittingham Trust.

The University of Wisconsin Press

728 State Street, Suite 443

Madison, Wisconsin 53706

uwpress.wisc.edu

Grays Inn House, 127 Clerkenwell Road

London EC1R 5DB, United Kingdom

eurospanbookstore.com

Copyright 2020 by Lori Soderlind

All rights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any format or by any meansdigital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwiseor conveyed via the internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. Rights inquiries should be directed to .

Printed in the United States of America

This book may be available in a digital edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Soderlind, Lori, author.

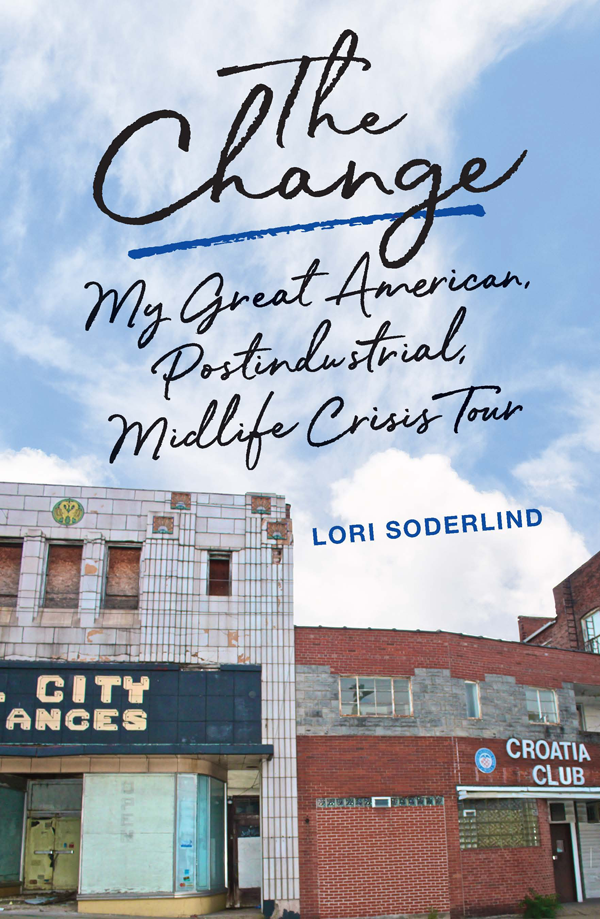

Title: The change: my great American, postindustrial, midlife crisis tour / Lori Soderlind.

Other titles: Living out.

Description: Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, [2020] | Series: Living out: gay and lesbian autobiographies

Identifiers: LCCN 2019050469 | ISBN 9780299328306 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Soderlind, LoriTravelUnited States.

Classification: LCC PS3619.O3775 Z46 2020 | DDC 818/.603dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019050469

Book epigraph 2020, 2005 June M. Jordan Literary Estate Trust. Reprinted by permission. www.junejordan.com. From June Jordan, Directed by Desire: The Collected Poems of June Jordan, edited by Sara Miles and Jan Heller Levi (Copper Canyon Press, 2005).

This is a memoir. It is a fact-based personal narrative created through careful notes, research, and memory. Some of these memories may contain embellishments, to aid storytelling, but no facts have been changed. Names have been changed to protect the privacy of some who did not expect to turn up in the pages of a book. All photos in this book are by the author.

ISBN-13: 978-0-299-32838-2 (electronic)

For Suzanne

There is no chance that we will fall apart.

There is no chance.

There are no parts.

June Jordan,

Poem Number Two on Bells Theorem

I

1

A Prelude

I had been thinking for a long time of driving out into the middle of the country with my dog. Names on maps and highway signs had been tempting me all my life, and I figured I would do it one day; I would go off on a simple kind of where the hecks Paducah? meander across the continent with no particular story to tell. Just curiosity. I would search for junk-shop treasures in little towns I had never heard of. I would find all types of new places to drink coffee. My dog, Colby, was getting old; if we were ever really going on this journey together, it couldnt wait much longer. And we were definitely going. Eventually. But time passed and nothing happened and the dream remained a dream.

Until the night of the crisis. Apparently, a crisis was needed if I was ever going to leave, and when a crisis is needed, one will come. Believe me. In shortand I hesitate to say this, but it must be saidone night in the early summer of my dogs thirteenth year, I cheated on my girlfriend. And after that, leaving was easy. After that, I had to flee.

Of course, to say I cheated is a bit of an exaggeration; the violation occurred strictly in theory. I did not touch anyones body and no other body touched mine. Thats part of the confusion of the whole affair; there was no affair, really. The trouble was in my mind. I was a woman of a certain age, with a fine life constructed around me like church walls; if anythingwas missing, I thought, it was only a little time to wander off, to feel more like myself for a while. But my mind has a mind of its own, and one night, inside those church walls, my mind was torridly unfaithful. To have felt so determined to act on impulse, to break the agreement I had built my life onthat woke me up. Yes, it did.

Also, I should add that when I say I cheated on my girlfriend, the word girlfriend doesnt quite fit either. I had been with my partner about thirteen years (just a bit less time than I had been with my dog) and I was nearly fifty when the crisis arrived; fifty was not as old as Colby in dog years but still, I was hardly a girl. So when I confess that I cheated on my girlfriend one night, technically not a word of it is true. But words are as flawed as I am, it seems. They mean well; they fail. What matters is, I really was in trouble.

The nonevent Ive called cheating occurred on a June visit to my familys cabin in northern Wisconsin, which also involved a drive, though not quite such a long one. A prelude. I probably never would have cheated if I had never left home, but then there I was, in peril, in Wisconsin. My family has roots six generations deep in Wisconsin, which makes the cabin one of the few things in this world that feels absolutely certain. Everything elseand everybody, I see nowcomes and goes, no matter how beloved. Its all fungible. But not the cabin. The cabin sticks. Its like the one true thing, though I shouldnt say this; I fear it might burn down now.

Colby and I drove out to the cabin that June just as I had driven so many times before, at least once a year all my life and lately often more. Its a 1,200-mile drive from New York, where I live; it takes twenty hours to get there. The route passes Cleveland and Sandusky; Angola and South Bend; Gary, Indiana, and Rockford, Illinois, a chain of mysterious places I had, over fifty years, wondered about but never seen. Not really. On our way to the cabin that June, Colby and I stopped for the night in Erie, Pennsylvania, a city we normally would have seen nothing of beyond the motel parking lot; we were only there to sleep, after all. But on this trip, I did something different, and everything changed. I might have known this one change would open up a floodgate. I might have kept on doing everything just the same instead, had I known. But on this trip, faced with unsatisfying motel-brewed coffee in a tiny foam cup, it occurred to methat I wanted something better for myself, that in fact I deserved more, and that if I looked, I could find it. I might even find what I wanteda real coffee shop with scones and everythingright in downtown Erie.

Which begged the question: Did downtown Erie exist? And if it did, why had I never seen it? For all I knew, Erie, Pennsylvania, was in fact nothing more than a knot of motels and chain restaurants along the interstate. Its entirely possible to be somewhere without ever being there at all. But my addiction to caffeine set me off that day in search of real Erie, wherever that was, and if there was no real Erie I might at least find a Starbucks. Then, before I found any of this, something else happened: I made a fateful turn and traffic whisked me off to a place called Presque Isle State Park. And boy, that was another place entirely.

The moment I entered that park, Colby sat up in the back seat and started panting like he knew something good was going to happen or, maybe, like he had to pee; I was never absolutely certain what Colbys panting might mean, but it always meant something. I figured I better pull over.

Presque Isle State Park has a gorgeous beach, so unspoiled and peaceful. How had I not known? Why had I never been there? We went for a walk on that beach, where Colby limped spritely across the sand ahead of me, pulling on his leash like a geriatric reindeer tethered to my reins. Arthritis in his legs had slowed but not stopped him. He pulled me right to the water and stepped in to take a little sip of Eriea Great Lake once so polluted that it caught fire. The fire was big news in 1969. Fires in other Great Lakes and rivers were in the news too; they burned with alarming frequency in those days. I remember thinking as a girl, But Mommy, water cant burn, then realizing it wasnt the water that was burning, then feeling terrified. Humans can really mess things up. Colby took a long drink from the lake, then I steered him around the big, terribly dead fish carcasses washed up in the sand, which his nose hunted avidly but his dim eyes couldnt see. Across the bay stood boxy concrete buildings with smokestacks, which looked to me like the last gasps of once enormous and water-fouling industries. Or sewage plants, possibly. It would spoil the memory to know.