DR. NOAH CHARNEY IS THE INTERNATIONALLY BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF more than a dozen books, translated into fourteen languages, including The Collector of Lives: Giorgio Vasari and the Invention of Art, which was nominated for the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in Biography, and Museum of Lost Art, which was the finalist for the 2018 Digital Book World Award. He is a professor of art history specializing in art crime, and has taught at Yale University, Brown University, American University of Rome, and University of Ljubljana. He is founder of the Association for Research into Crimes against Art (ARCA), a groundbreaking research group (www.artcrimeresearch.org), and teaches in its annual summerlong Postgraduate Program in Art Crime and Cultural Heritage Protection. He is a regular on television and radio, presenting programs for the BBC and Discovery, among others, and his TED Ed videos have been viewed by millions. He writes regularly for dozens of major magazines and newspapers, including the Guardian, the Washington Post, the Observer, and theArt Newspaper. His other books published by Rowman & Littlefield include The Devil in the Gallery: How Scandal, Shock and Rivalry Shaped the Art World and Making It: The Artists Survival Guide. He lives in Slovenia with his wife and children and their hairless dog, Hubert van Eyck (believe it or not). Learn more at www.noahcharney.com.

BOOKS ARE COLLABORATIVE PROJECTS. THE AUTHOR IS THE ARCHITECT, bricklayer, and carpenter, but there are all manner of tradesmen involved throughout, helping to improve the finished product. Im grateful to the team at Rowman & Littlefield for entrusting me with this, our third book together.

Charles Harmon is a wonderfully supportive editor and Erinn Slanina has ably assisted on all three. The promotional team and the external publicists at Pubvendo have been a pleasure to work with. Thanks, as always, to my intrepid agent, Yishai Seidman. To my art history teachers who shaped my love for the field: Veronique Plesch, Michael Marlais, David Simon, Sheila McTighe, and Madame Poupard, who took me throughout Paris when I was living there as a cow-eyed sixteen-year-old. Thanks also to Refik Anadol and Tom Ross, as well as to the Gagosian Gallery, JAA, and Meta Grgurevi, for generously allowing us to use their images. I must thank all my students, from young teens to octogenarians, who have taught me how to teach in a way that didnt feel like anyone was learning (for those for whom the term does not inspire affection).

Lets smash the intimidation that glasses in art.

This book is your hammer.

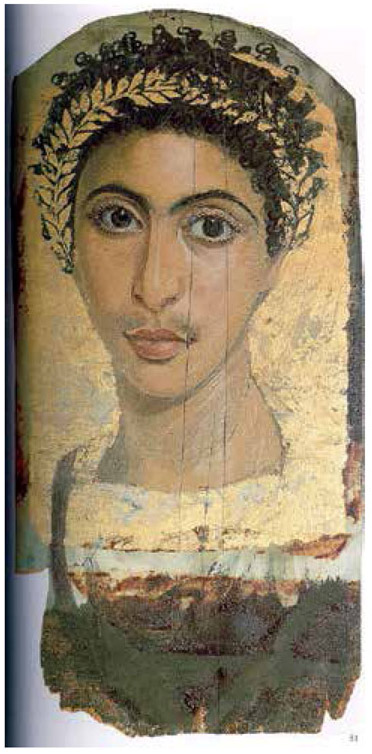

Key Work:Fayum Mummy Portrait (circa third century CE)

ART HAS AN INTIMIDATION PROBLEM. IT ALSO HAS AN ELITISM PROBLEM, and these two elements are linked.

There are too many people who feel that art is not for them, that they wont get it and therefore do not want to try, even if they think they might like it. And there are certain communities within the art world that seem to enjoy the sense that art is a private club, that not everyone is invited.

What a silly idea.

I am a proponent of making art feel accessible to anyone who is willing to meet it halfwayto give it a little bit of attention, to be open-minded and not dismissive. The dismissive approach (i.e., I dont like modern art because I could do it) is usually borne of fear of not understanding (and feeling diminished because of this).

Theres no need. Art has endless levels of study and understanding, but a broad and quite deep basic white belt in art is not hard to achieve. I have heard powerful insights from people without any degrees at all and Ive heard hot air and nothingness from bow-tied gents with PhDs. You do not need extensive training to understand art, much less to enjoy it. Consider the art critic Jerry Saltz. He is one of my favorites to read, he offers brilliant insights, and he is almost entirely self-trained, having turned to art criticism with a background in art handling (he worked for an art delivery service).

I am stridently antielitist. One of the reasons I can get away with this stance is that I come from within the club. Ive studied at fancy institutions, I have a PhD and a pair of masters degrees, I spent time working at museums and auction houses, and Ive taught at top universities. But Ive never been interested in speaking to a closed group of peers who are often so busy with infighting that they wind up typing (or sometimes shouting) into an echo chamber, just bouncing ideas, arguments, and jealousies off one another in a grumpy game of badminton played on a court paved with pages of peer-reviewed academic journals. This is of no interest to me.

This is one of a number of strikingly naturalistic painted portraits accompanying mummies found in the Hellenistic city of Antinoopolis in what is today Egypt, made circa the first century CE. This gentleman looks as though tonight hes gonna party like its 1999. PHOTO COURTESY OF WIKIART BY ELOQUENCE.

Thats why I write for popular magazines and newspapers, publish best-selling books, and host TV programs. I feel more like Ive succeeded if the taxi driver taking me to my talk at the National Gallery is familiar with my work than I would with the professor who is about to host me there. My goal is to make art as accessible, understandable, enjoyable, and intriguing as possible for as many people as are willing to be open-minded and consider engaging with it.

This is the goal of the book in your hands, with its intentionally reductionist title and subtitle. Of course you wont become a true expert in just twelve hours or by reading any one book. But the leap you will feel between the first page and the last will be the most exten sive jump possible, the one that brings the most satisfaction and a feeling of empowerment that you can and do understand a world that, before you began reading, felt complex and intimidating. I have taught art history at every level, from high school students to postgraduates and even fellow professors. My favorite age group to teach is the youngest one, because the leap in knowledge, from right around zero to cruising speedthe feeling that, yes, you can do this; you can understand and fully enjoy artis the most palpable and significant. They key is tearing down the ramparts of intimidation, lifting portcullises of jargonof long words in foreign languages, of endless-ismsand making even the complicated ideas feel clear, simple, and accessible. Doing this successfully is the mark of a good teacher and a good writer.

This intro level to covering all the basics is as useful for young readers as it is for adults. It is designed to be the book you should read if you are only going to ever read one book about art. But you could also think of it as a benevolent gateway drug, a concise wardrobe through which you walk, passing into the magical, wondrous world that is art.

The format is intentionally streamlined. Twelve chapters are built around a big idea and a famous masterpiecethe sort youll find in Art History 101 books, the art you really should know and that offers a useful point of reference. I mention many other works along the way, but this isnt meant to be a lavishly illustrated book. There are two chapters covering art history that include a flurry of artworks, and any that are not reproduced in this book are just a quick internet search away. I will reference other works as we go, but the core is reduced to an easily digestible, easy-to-remember ore of beauty and information.

Reductionism is an established approach by scientists: You take a giant problem that feels impossible to solve and either slice it into bite-sized pieces, each one of which feels manageable, and thus slowly work your way to solving the entirety, or you boil down the big problem into the most basic possible form that feels easier to handle. Nobel Prize winner (and occasional art historian) Dr. Eric Kandel unlocked the secrets of how the human brain works by using a reductionistic approach. The human brain is vastly complex, so he focused his studies instead on a brain that is physically as large as possible yet as uncomplex as possible. He settled on the brains of giant sea snails. These proved much easier to analyze, and the information gleaned was applicable to human brainsand led to a Nobel Prize. (He also authored a book called