CASS SERIES ON INTELLIGENCE AND MILITARY AFFAIRS

Studies in Intelligence Series No. 4

A DON AT WAR

CASS SERIES ON INTELLIGENCE AND MILITARY AFFAIRS

Studies in Intelligence Series

Editors: Christopher Andrew and Michael I. Handel

1. Leaders and Intelligence edited by Michael I. Handel

2. Codebreaker in the Far East by Alan Stripp

3. War, Strategy and Intelligence by Michael I. Handel

4. A Don at War by Sir David Hunt

(revised edition with new introduction)

Sir David Hunt by Karsh, 1946

A Don at War

SIR DAVID HUNT

K.C.M.G., O.B.E.

With a Foreword by

Field Marshal the Earl Alexander of Tunis

K.G., P.C., G.C.B., O.M., G.C.M.G., C.S.I., D.S.O., M.C.

First published 1966 by

FRANK CASS & CO. LTD

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1990 David Hunt

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Hunt, Sir, David 1913

A don at war.

1. World War 2. Army operations by Great Britain. Army. Biographies

I. Title

940.548141

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hunt, David, Sir, 1913

A don at war / David Hunt.

p. cm. (Cass series on politics and military affairs in the twentieth century)

Reprint, with new introd. Originally published: London : Kimber, 1966

1. Hunt, David, Sir, 1913 . 2;. World War, 19391945Secret serviceGreat Britain. 3. World War, 19391945Personal narratives, British. 4. Great Britain. ArmyBiography. 5. Intelligence officersGreat BritainBiography. 6. Military intelligenceGreat BritainHistory20th century. I. Title. II. Series.

D810.S7H85 1990

940.548641092dc20

89-71272

CIP

ISBN 13: 9780714633831 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 9780714643748 (pbk)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

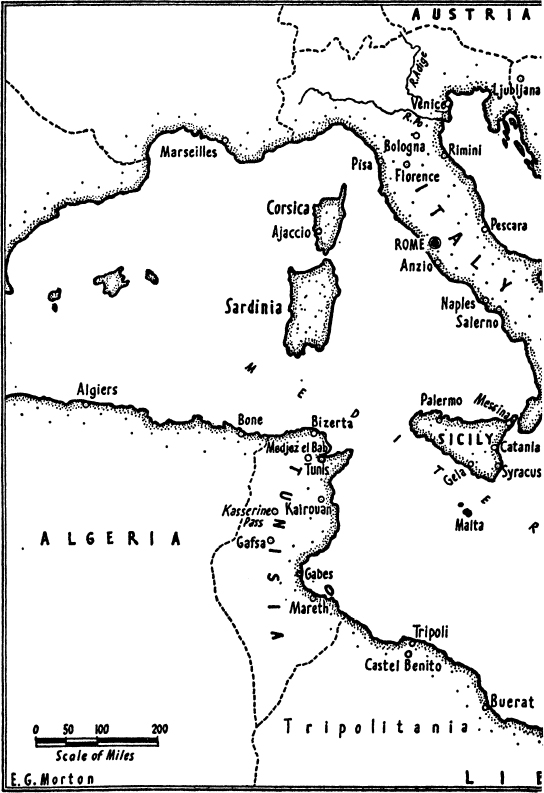

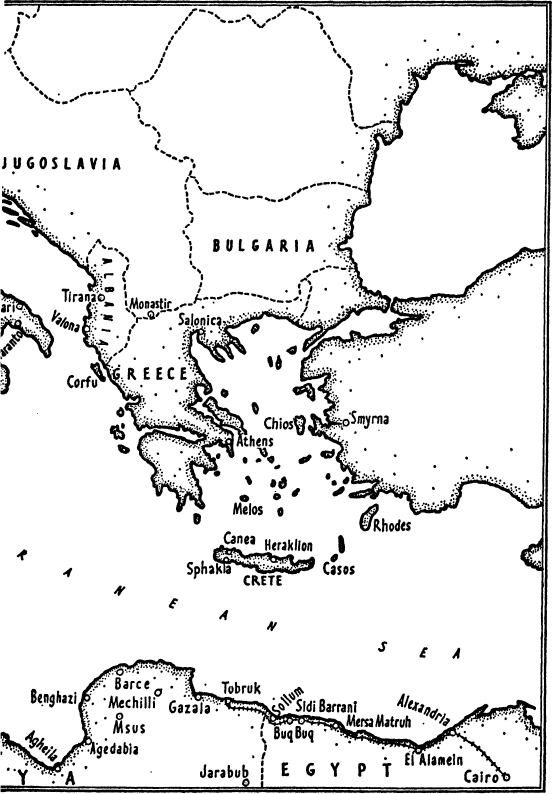

Foreword to the 1990 Edition

T HIS BOOK was first published in 1966. What I had principally in mind in writing it was to entertain two young sons by telling them what I had been up to during the war. This accounts for the predominantly anecdotal style. I dont in fact regard anecdotes as beneath the dignity of history. Nor did either Herodotus or Macaulay, who are the historians I most enjoy and admire. I also thought it might be of value to future historians if I put down my view of the events of which I had personal experience during the time I served abroad, from 1940 to 1945. With this in mind I did take a good deal of trouble to ensure, from such papers as I had preserved and from official publications, that the narrative of events was accurate because it seemed to me that an enormous amount of what had been written about the campaigns in Africa and Italy was seriously misleading, either romanticised or distorted to suit the particular prejudices of the writer. The publication of the official histories has now provided a standard against which those earlier works can be judged; but when I began writing, which was before 1960, there was not much available that was authoritative outside the official despatches. When the final draft was ready I showed it to Field-Marshal Lord Alexander, my old chief. He was good enough to encourage me, and to write a Foreword, and William Kimber accepted it.

The first edition was exhausted fairly rapidly. Reviewers were generally benevolent. What pleased me even more as time went by was to find that the book was very frequently quoted as an authority in the footnotes of the official history of the war in the Mediterranean and Middle East and also in Professor Sir Harry Hinsleys four-volume official history of British Intelligence in the Second World War. More recently it has acquired readers in the United States Army War College, the equivalent of our Staff College at Camberley, from where Michael Handel, Professor of National Security Affairs, has informed me that he has found it useful for his lectures on deception, particularly in the Italian campaign. (The official account of deception by Sir Michael Howard, which will without doubt be a magisterial work of final authority, has not yet been published.) Accordingly when Frank Cass proposed to me to publish a second edition, 24 years after the first, I was glad to agree.

For the benefit of any bibliographers who may be interested I should add that a Portuguese translation was published in 1973 by the publishing house Paz e Terra of So Paulo under the title Um Professor na Guerra. I was Ambassador in Brazil at the time, which is probably sufficient explanation.

This new edition, at the suggestion of Frank Cass with which I fully concurred, is a straight reprint of the original except for a very few typographical corrections. I feel sure this is right. The text goes back to the period immediately after the war and reflects the work I had done on the first draft of the official history and on Lord Alexanders despatches. It has at least the merit of representing a consistent point of view formed at a certain time and with a single exception that I am about to mention there is little of importance that it is necessary to add or to correct.

The principal purpose of this Foreword is to make good that one great omission: the fact that the British were able to read German high-grade ciphers. These were produced by special machines called Enigma and the Germans were convinced, right up to the end of the war and after, that the texts they produced were indecipherable. In consequence of this success, during the whole period I am dealing with, signals passing between the senior commanders of the enemy forces were intercepted, deciphered and sent to our commands abroad. There were naturally many gaps but generally speaking a remarkable degree of continuity was maintained. It was this more than anything else that accounted for the accuracy of the forecasts that British Intelligence was able to make of enemy strategic intentions; in addition, because it was also possible to read the traffic passed between German Intelligence stations, we were able to assess the effect on the enemy of our programmes of deception and to protect the security of our operations.

It was the greatest secret of the war. Its preservation must be regarded as almost miraculous. To break the ciphers encrypted by the Enigma machine was an extraordinary intellectual achievement but it would have been sterile if the information received had not been disseminated at once to the forces in the field who could use it. This meant that there were thousands in the secret. They had all been warned against any disclosure, or carelessness in handling the material. Having been selected as persons of more than average intelligence they could see for themselves the value of the work they were doing and how easy, and how fatal, any betrayal would be. Some may have believed the widely-circulated story that Churchill personally had threatened that the person who lost us this great advantage would be sent before a firing squad; but it was not necessary. Even more surprising is the fact that the secret continued to be kept after the war. I have heard many stories of wives who had spent four years of their lives at Bletchley Park, the centre for decipherment, and never told their husbands what they had done there. They were horrified and felt cheated when the great secret appeared in the bookshops.