Table of Contents

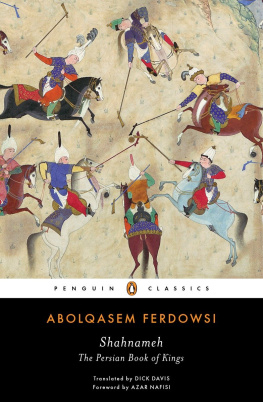

PENGUIN CLASSICS

DELUXE EDITION ROSTAM

ABOLQASEM FERDOWSI was born in Khorasan in a village near Tus, in 940 CE. His great epic the Shahnameh, to which he devoted most of his adult life, was originally composed for the Samanid princes of Khorasan, who were the chief instigators of the revival of Persian cultural traditions after the Arab conquest. During Ferdowsis lifetime, the Samanid dynasty was conquered by the Ghaznavid Turks. Various stories in medieval texts describe the lack of interest shown by the new ruler of Khorasan, Mahmud of Ghazni, in Ferdowsi and his lifework. Ferdowsi is said to have died around 1020 in poverty and embittered by royal neglect, though confident of his and his poems ultimate fame.

A fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, DICK DAVIS is currently professor of Persian at Ohio State University. His other translations from Persian include Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings; Vis and Ramin; Borrowed Ware: Medieval Persian Epigrams; My Uncle Napoleon; The Legend of Seyavash; and, with Afkham Darbandi, The Conference of the Birds.

INTRODUCTION

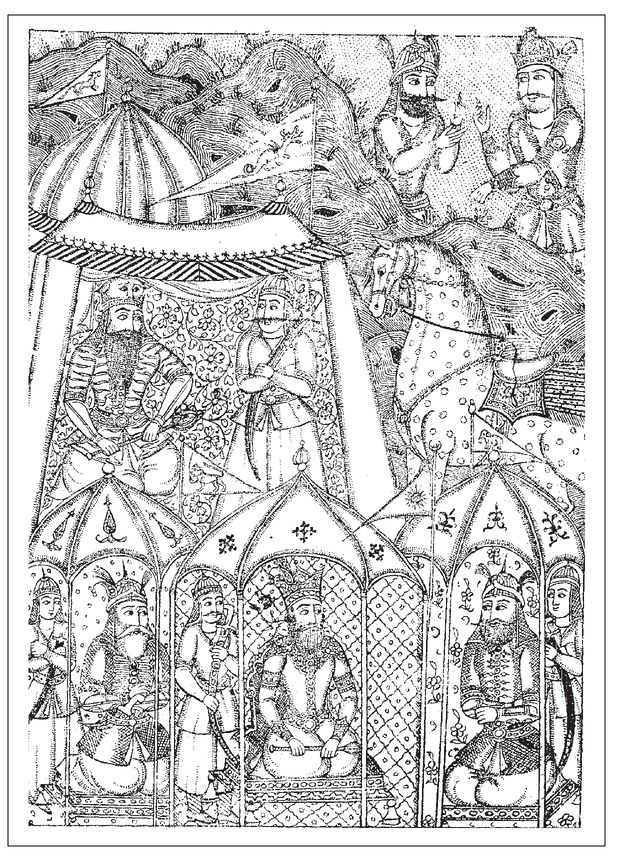

Rostam is the greatest hero of pre-Islamic Persian legend, and he and his exploits dominate the first half of our principal source for such material, the Shahnameh, the magnificent compendium of verse narratives concerned with pre-Islamic Iran that was written down by the poet Ferdowsi at the end of the tenth and the beginning of the eleventh centuries C.E.

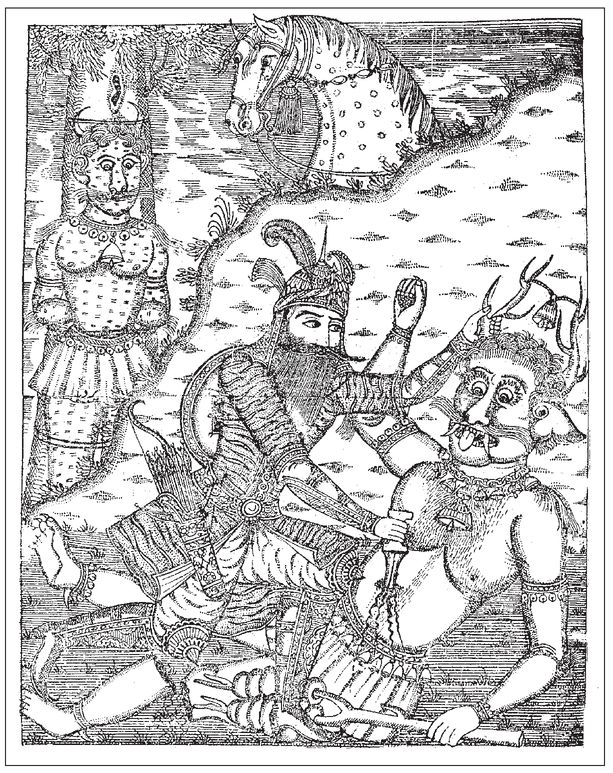

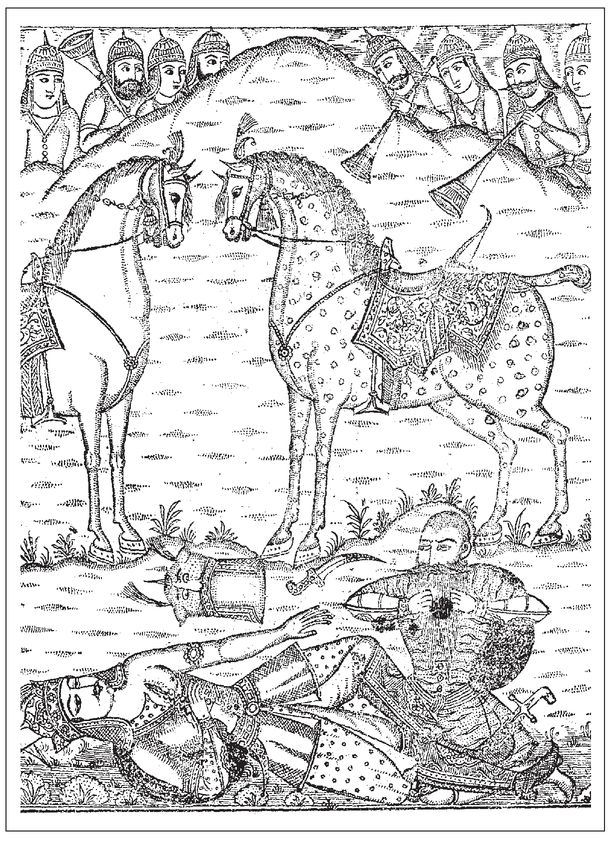

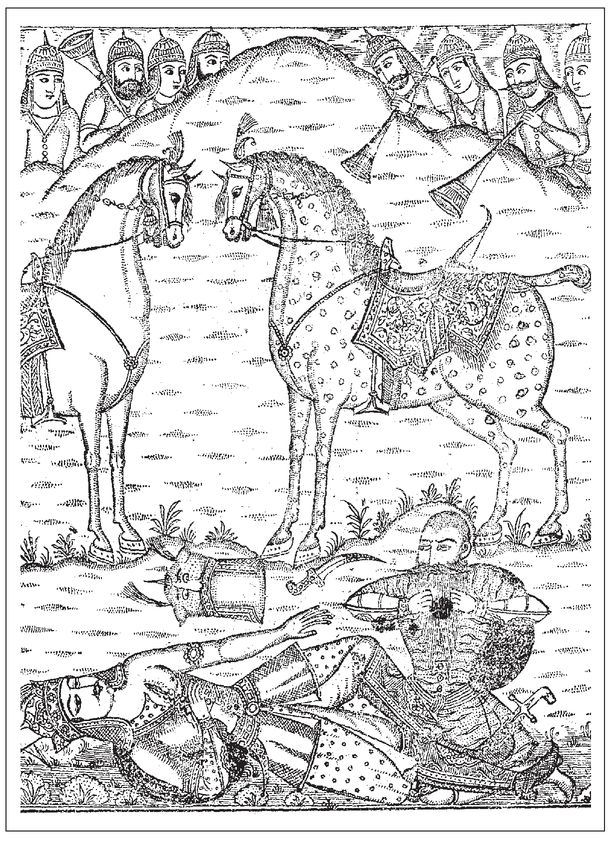

As befits an ancient hero he is a larger-than-life figure: he lives for over five hundred years, he undergoes seven trials of strength, cunning, and endurance that put him in the same company as Hercules and his labors, he defeats and kills not only innumerable human enemies but also dragons and demons, he serves as the pre-eminent champion of no less than five Persian monarchs and lives through much of the reigns of two more. After his death, he is constantly evoked by those who come after him as the epitome of magnanimity, manliness, heroism, and loyalty to the Persian throne. The stories in which he figures are the best-known and most loved narratives of the Shahnameh, and are among the most famous in Persian culture.

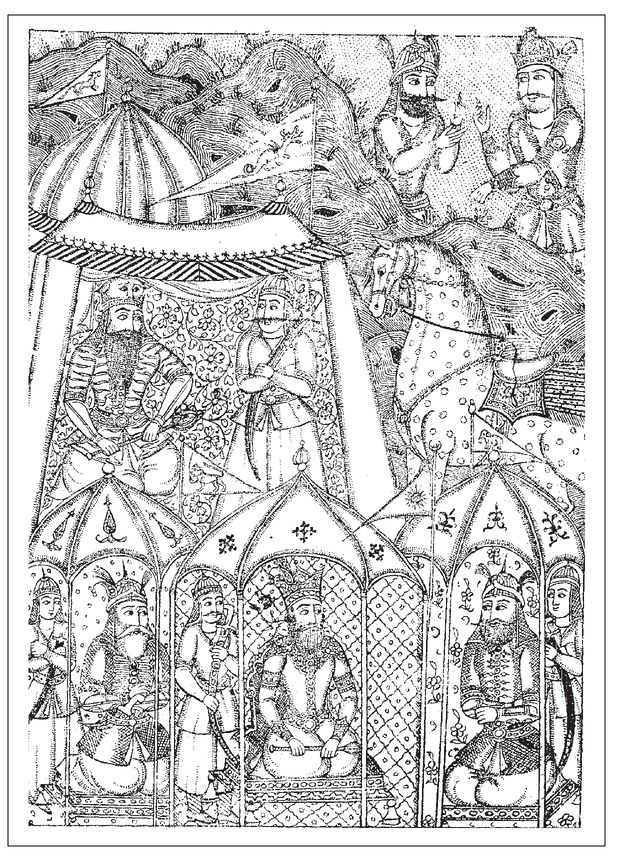

But Rostam is not simply a paragon of heroic loyalty to the Persian throne mythologized and writ large. Something that runs throughout all the narratives in which he is involved is his insistence that he is his own man, that his service is given voluntarily and cannot be constrained, and that he is at no ones beck and call, not even his kings. If he is loyal it is because he chooses to be, and sometimes he chooses not to be. There is something anarchic about him, a contempt for boundaries and borders (both literal and metaphorical ones), a stubbornness and eagerness to excel, which can remind a Western reader of Shakespearian heroes like Coriolanus or Warwick (called, as Rostam is too, the kingmaker), an overreaching that like theirs can lead directly to tragedy. Much of the glamour of Rostams legend lies in the tension between this fierce independence, which places him outside of authority, and his seemingly inexhaustible (until it is in fact exhausted) service to the Persian monarchy and the country it controls. If the Shahnameh is primarily, as its name (the book of kings) implies, about monarchy, and so about a center of absolute or would-be absolute power, Rostam is a figure from outside of that center of power; he is one who lives, in all senses, at the edge.

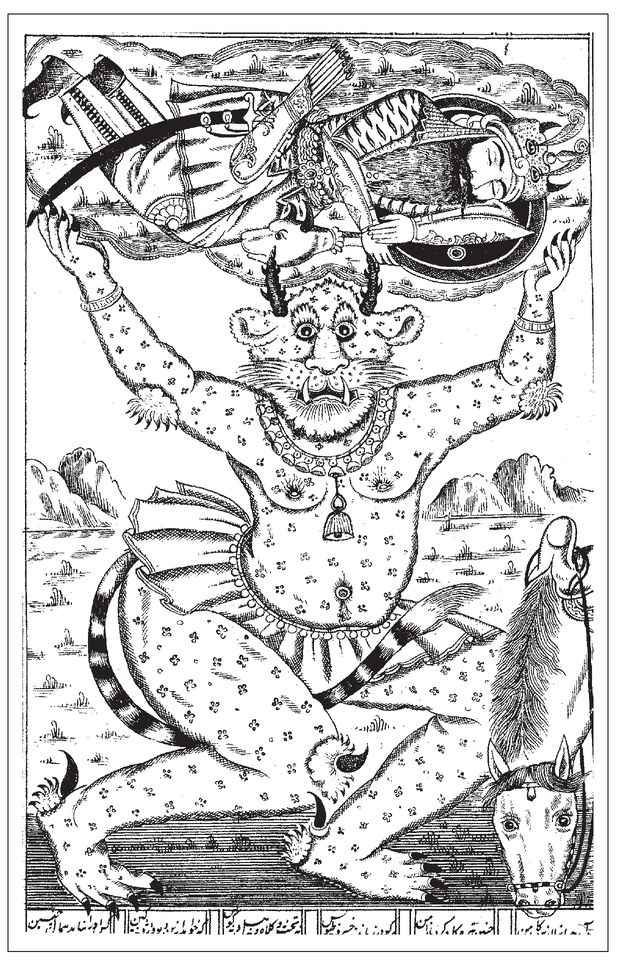

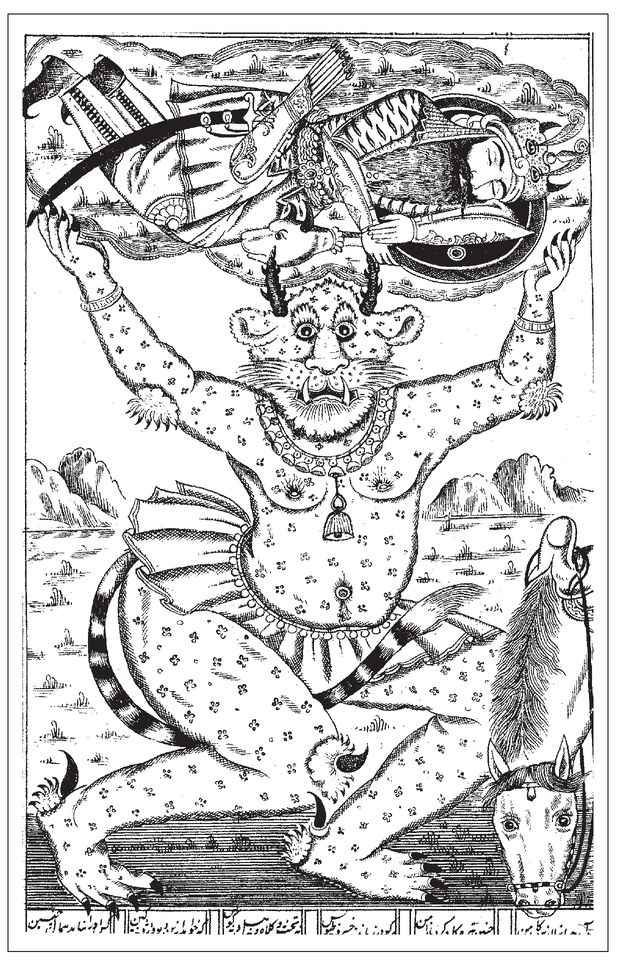

We can see this at the edge quality clearly in his origins, which indicate his tangential relationship both to the land of Iran and to humanity in general. His parents are the Persian hero Zal and the Kaboli princess Rudabeh. When Zal is born, his father exposes him on a mountainside to die because of his white hair and mottled skin, and he is brought up by a fabulous magical bird, the Simorgh. The implication is that there is something demonic about Zals appearance, and indeed there is only one other figure in the Shahnameh who is described as having white hair and a mottled skin, the White Demon of Mazanderan, whom Rostam kills in single combat, and who almost kills him. Once one has registered the similarity in the descriptions of the demons appearance and that of Rostams father, it is hard not to see this struggle as an Oedipal reversal of a common motif in the Shahnameh, the death of sons through the actions of their fathers.

When Zal has returned to the human world the Simorgh remains his protector, and she is later on (through Zal as an intermediary) the protector of his son Rostam; in their ability to call on her magical aid in moments of extreme peril they are given access to magical powers. The supernatural as part of Rostams inheritance, again in somewhat demonic guise, is even more evident on his mothers side: Rudabehs father is Mehrab, the king of Kabol, who is descended from the demon king Zahhak, from whose clutches Iran was freed by the noble king Feraydun. Zals king, Manuchehr, at first opposes Zals marriage to Rudabeh because this will mingle the demonic bloodline of Zahhak with that of the Persian heroes (and Rostam is the result of just such a mingling). In human terms then, Rostam is certainly at the edge: he can call on magic, he is descended from a demon on his mothers side, and his fathers strange upbringing and appearance also bring with them an aura of the supernatural and perhaps the demonic. Rostam is a great subduer of demons, but as with another Persian hero (and king this time) Jamshid, whose authority over demons seems at times to come as much from his participation in their world as his defeat of it, there is a suggestion of set a thief to catch a thief about his prowess.

Geographically Rostam belongs in Sistan, his familys appanage, granted in perpetuity by the Persian kings for their loyalty to the throne. The area may have been granted by the kings, but when Rostam is uneasy with the political goings-on at the Persian court, it is to this area that he retreats, where he is beyond the reach of the king unless he wishes to present himself of his own free will. Like Achilles, Rostam is often contumacious and moody, and Sistan is his equivalent of Achilless tent: its the place he goes to sulk, to indicate that he has washed his hands of his peoples problems.

The modern Sistan, the southeastern province of Iran, does not correspond with Zals and Rostams kingdom, which lies largely to the east of this area, in what is now the province of Helmand in Afghanistan. The river Helmand (called, in Ferdowsis time, the Hirmand) marks the northern border of their territory. Rostams land is therefore on the eastern edge of the Iranian world. His mother is from Kabol, and Rostam dies in Kabol, placing his origin and death even further to the east; indeed, in the terms of the

DELUXE EDITION ROSTAM

DELUXE EDITION ROSTAM