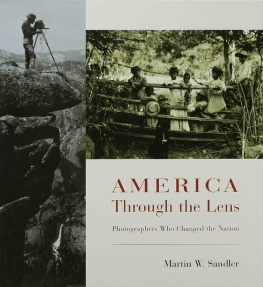

Seeing America

WOMEN

BETWEEN THE

Melissa A. McEuen

Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright 2000 by The University Press of Kentucky

Paperback edition 2004

The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky,

Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown

College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky

University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of

Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

08 07 06 05 04 5 4 3 2 1

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

McEuen, Melissa A., 1961

Seeing America : women photographers between the wars / Melissa A.

McEuen.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8131-2132-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

Women photographersUnited StatesBiography. Documentary photographyUnited StatesHistory20th century. PhotographyUnited StatesHistory20th century. I. Title.

TR139.M395 1999

770.92273dc21

[B] 99-17219

Paper ISBN 0-8131-9094-0

0-8131-9094-0 0-8131-9094-0 0-8131-9094-0 0-8131-9094-0 0-8131-9094-0 0-8131-9094-0 0-8131-9094-0 0-8131-9094-0

For

the McEuens

and

the Stantons

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Documentarian with Props

Doris Ulmanns Vision of an Ideal America

Portraitist as Documentarian

Dorothea Langes Depiction of American Individualism

A Radical Vision on Film

Marion Posts Portrayal of Collective Strength

Of Machines and People

Margaret Bourke-Whites Isolation of Primary Components

Modernism Ascendant

Berenice Abbotts Perception of the Evolving Cityscape

Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

THE PLASTIC CAMERA MY PARENTS GAVE ME on my eighth birthday had only two features, a shutter button and a neck strap. That such a simple box could create a world of images amazed me. For several years, I proudly displayed my black and white pictures as squares of captured time, shots of ordinary people going about their daily lives in my small western Kentucky hometown. Many years later I began probing the meanings of photographs, inspired by my graduate school mentor, Burl Noggle. He directed an early paper I wrote on realities in pictures taken in the 1920s. From there I expanded my arguments about visual images, first in a masters thesis and then in a doctoral dissertation, all the while sustained by Burls patience and encouragement.

My dissertation lies at the core of this book, and I want to acknowledge the financial support I received to complete both projects. The T. Harry Williams Fellowship in History at Louisiana State University allowed me a years leave, the valuable time necessary for sustained research. A generous faculty research grant from Georgetown College made it possible for me to spend a summer in Washington, D.C., and a Jones Faculty Development Grant from Transylvania University funded another research trip in 1997.

I received kind assistance from many cooperative and patient archivists, curators, and staff members at the Archives of American Art; the Art Department of Berea College; Special Collections at Berea College; the Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley; the J. Paul Getty Museum; the University of Kentucky Art Museum; the University of Louisville Photographic Archives; the National Archives; the New York Historical Society; the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; Special Collections at the University of Oregon; and the South Carolina Historical Society. Especially helpful were Lisa Carter, at the University of Kentucky Special Collections; Therese Thau Heyman, at the Oakland Museum; and Amy Doherty, at George Arents Research Library, Syracuse University. My unending gratitude goes to Beverly Brannan, Curator in the Prints and Photographs Division at the Library of Congress. Over the years we have discussed ideas, read each others manuscripts, and shared numerous stories about women who chose photography as a profession. Beverlys enthusiasm and wide-ranging knowledge in the field are blessings.

The comments offered by colleagues and members of the audience at several meetings, including those of the American Studies Association; the American Historical Association, Pacific Coast Branch; the Louisiana Historical Association; and the 1997 Doris Ulmann Symposium at the Gibbes Museum of Art, helped me to shape my positions on several issues. Fellow participants at the 1995 National Endowment for the Humanities Institute, The Thirties in Interdisciplinary Perspective, directed by John and Joy Kasson at the University of North Carolina, prodded me with thought-provoking questions that strengthened the book. I extend special thanks to Robert Snyder for his insights on my work and for taking a chance on a young scholar by inviting me to contribute to a special issue of History of Photography that he edited. Those who have read all or parts of the manuscript and whose invaluable comments have enhanced it beyond measure include Jessica Andrews, Peter Barr, Robert Becker, Beverly Brannan, James Curtis, Gaines Foster, the late Sally Hunter Graham, Philip W. Jacobs, Wendy Kozol, Heather Lyons, Richard Megraw, Mary Murphy, Daniel Pope, Janice Rutherford, Charles Thompson, and Alan Trachtenberg. An anonymous reader for the University Press of Kentucky offered excellent suggestions. In the Social Science Division Office at Transylvania University, Linda Denniston helped me tremendously and usually on short notice.

Those familiar with liberal arts colleges devoted to undergraduate education know that time for research and writing is precious; there are no teaching assistants or graders, and teaching loads are heavy. So I remain awed by the example of my former Georgetown College colleague, Steven May, who has gracefully balanced his roles as an award-winning teacher, a faculty leader, and a prolific scholar for thirty years. His sound advice and hearty encouragement were extremely important when I was starting out in the academic world.

Loving friends have been with me at the times I needed them mostI am lucky to be able to share secrets and an occasional breakfast, lunch, or afternoon tea with Sharon Brown, Barbara Burch, Regina Francies, and Mary Jane Smith. As always, the warm embrace of my parents, Bruce and Peggy McEuen, and my brothers, Kevin McEuen and Kelly Brown McEuen, has been constant and life-sustaining. The family that I married into about the time I began writing this book also have given me their unconditional support. No one has lived with this project more than my husband, Ed Stanton. As a scholar, he knows the rigors of academia and so has carefully protected my solitude. As a companion and lover, he keenly understands what the most essential things in life are and has passionately safeguarded our time to enjoy them together. He not only made this book possible but allowed its creator to thrive in the sweetest Eden imaginable.