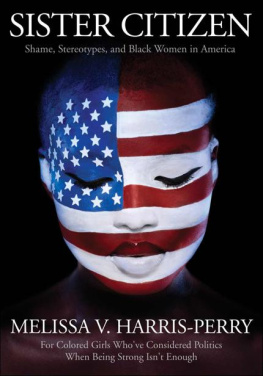

Sister Citizen

SISTER CITIZEN

Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America

Melissa V. Harris-Perry

Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2011 by Melissa Victoria Harris-Perry.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the US Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (US office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (UK office).

The publisher gratefully acknowledges permission to reproduce the following: Elizabeth Alexander, Praise Song for the Day, from Crave Radiance: New and Selected Poems,19902010, copyright 2009 by Elizabeth Alexander, reprinted with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, www.graywolfpress.org; No Mirrors in My Nanas House, copyright 1998 by Ysaye M. Barnwell, reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company; Resisting the Shaming of Shug Avery from The Color Purple, copyright 1982 by Alice Walker, reprinted by permission of Harcourt, Inc.; excerpt from Their Eyes Were Watching God, by Zora Neale Hurston, copyright 1937 by Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc.; renewed 1965 by John C. Hurston and Joel Hurston; reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers; Kate Rushin, The Bridge Poem, reprinted by permission of the author.

Set in Bulmer type by Keystone Typesetting, Inc., Orwigsburg, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Harris-Perry, Melissa V. (Melissa Victoria), 1973

Sister citizen : shame, stereotypes, and Black women in America / Melissa V. Harris-Perry.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-16541-8 (clothbound : alk. paper)

1. African American womenPolitics and government. 2. African American women PsychologyPolitical aspects. 3. Stereotypes (Social psychology)United States. 4. African American womenSocial conditions. I. Title.

E185.86.H375 2011

305.48896073dc22

2011015860

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For James, who is my Tea Cake...

except the part where she shoots him

For Blair, who is my Charlotte...

except the part where she dies young

For Parker, who is my everything... and always will be

Contents

Acknowledgments

It has taken me an excruciatingly long time to write this book. I had my first glimmer of insight about the themes explored here more than ten years ago. The past decade has been full of dizzying success, failure, joy, loss, passion, betrayal, and change. I have put down and picked up this manuscript a thousand times. I have loved and hated it in rapid succession. I have defended it fiercely and thought of abandoning it entirely. I have never been alone as I have alternately sprinted and limped to the finish line of this project. I have been accompanied by an astonishingly loyal group of scholars, friends, students, loved ones, and critics who have pushed, prodded, and poked in an effort to get this book out of me and onto the page.

I owe so much to all the teachers who believed in me along the way. Mrs. Erickson introduced me to the love of literature in eighth grade. Allen Ramsier gave me permission to take the path less traveled. Maya Angelou held my hand through the sometime difficult years of college and launched me into an academic career. John Brehm and John Aldrich made sure I made it to the finish line. Thank you to Gary Dorrien, Katie Cannon, and my fellow travelers at Union Theological Seminary who renewed my love of experiencing the classroom as a student. I will be satisfied if I give my students even a fraction of what you each gave me.

I am grateful to my colleagues whom I first met during my years at the University of Chicago. Tracey Meares remains my friend, supporter, and inspiration as a black woman in the academy. Jaciqueline Stewarts humor, insight, and kindness are beyond compare. As my senior colleague, Michael Dawson always ensured I had the resources and time to write. As my unyielding mentor, Cathy Cohen always made sure I had something about which to write. My interest in the politics of recognition is a direct result of having an office on the same hall with Patchen Markell for seven years. During those same years Jacob Levy planted my persistent skepticism with the assumptions of political science. Healthy competition with Daniel Drezner provided the impetus for taking my ideas beyond the academy and into the public realm. The Workshop on Race and the Reproduction of Racial Ideologies challenged and critiqued my work and forced me to think through new approaches and questions. John Cacioppos Social Psychology Workshop is where I first encountered the research on shame that fundamentally shaped this project.

At the University of Chicago I was surrounded by fantastic graduate students. They are now successful professionals and scholars in their own right. These men and women went out into neighborhoods to distribute surveys, they helped me cull extant literature, they searched archives, and they helped me clarify complicated ideas. Thanks to Stephanie Allen, Elizabeth Todd, Tehama Lopez, Quincy Mills, Ezekiel Dixon-Roman, Pam Cook, Chris Deis, Rovana Popoff, Bill Clark, Tanji Gilliam, Sujatha Fernandes, and all the other brilliant students who contributed to my research over these years. I can never repay the debt I owe to Bethany Albertson, whose careful and responsive research assistance buoyed me for years and whose friendship continues to light my path. Erica Czajas research support carried this project the last leg of the journey.

I am incredibly grateful to the undergraduate and graduate students at Princeton University who inspired and supported this book project in many ways. Megan Franciss diligence, intellect, and undeniable snark made my darkest moments in Princeton bearable. Emery Whalen, Farrell Harding, Abena Mackall, Cindy Hong, Kyle Hotchkiss-Carone, and Molly Alacron are just a few of the magnificent students who inspired, directed, and supported my work during the past five years. Many thanks to Gayle Brodsky, whose competence and diligence are the only reason I survived three years as director of undergraduate studies. Thanks are due to Nicole Shelton for walking the canal with me and for reading the psychology chapters and to Daphne Brooks for her careful reading of the introduction. Thanks also to Melvin McCray, whose encouragement, partnership, and energy led to great collaborations in teaching and research. No one was more important to my years at Princeton than Yolanda Pierce. We shared The Kitchen Table, cheered on each others daughters, drank a thousand gallons of coffee, complained endlessly, and celebrated unceasingly. Thank you for reminding me why we show up to do this work.

I am profoundly thankful to Professor Henry Louis Gates. He gave me a regular platform for my public writing, invited me to deliver the Du Bois lectures, and has treated me to some of the best dinners of my life. Even when we have disagreed, he has always supported my work and cleared a path for me to walk. Elizabeth Alexander and Kimberle Crenshaw are the sister professors whose kindness, support, intellect, and friendship still take my breath away. Thanks to Jonathan Metzl, who believed in the project when it was little more than an idea. Thank you to Lisa Gaines McDonald, who conducted my focus groups. And many thanks to the American Academy of University Women, whose fellowship supported this project in its early phases. Thanks to Marc Lamont Hill for being my friend and writing partner. Thanks to all my African American colleagues in professional political science who have shared the often rough journey from graduate school to tenure and beyond.

Next page