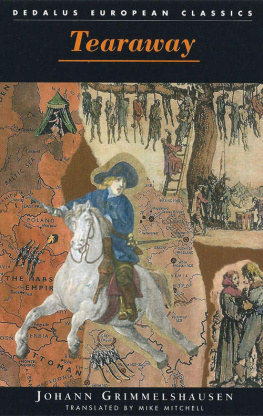

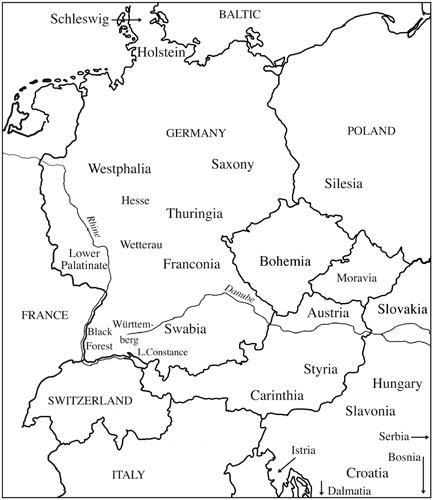

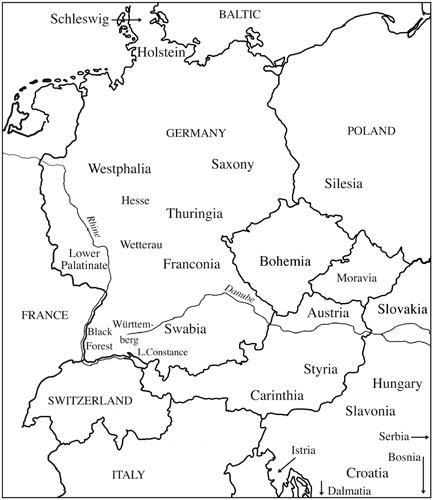

A map indicating the main regions of Tearaways travels. The boundaries are modern.

Mike Mitchell is one of Dedaluss editorial directors and is responsible for the Dedalus translation programme. His translations include the novels of Gustav Meyrink, three by Herbert Rosendorfer and Grimmelshausens Simplicissimus and Courage. His latest include The Maimed by Hermann Ungar, Tales from the Vienna Woods by Horvath and the expanded edition of his anthology, The Dedalus Book of Austrian Fantasy 18902000.

His translation of Rosendorfers Letters Back to Ancient China won the 1998 Schlegel-Tieck German Translation Prize.

Young Tearaway they called me, and I lived up to my name,

Went to war and risked my life in search of wealth and fame.

But Fate and Fortune, Time as well, decided otherwise,

Of booty, glory, I had none, a wooden leg my prize.

My wretched life exemplifies a story often told:

A dashing soldier in his youth, a beggar when hes old.

Contents

Tearaway (Der seltzame Springinsfeld, first published in 1670) is the third of Grimmelshausens novels round the figure of Simplicissimus, the first two being The Adventures of Simplicius Simplicissimus (Dedalus 1999) and the second The Life of Courage (Dedalus 2001). As far as I am aware, this is the first translation of Springinsfeld into English.

Tearaway begins with the conjunction of Saturn, Mars and Mercury. Grimmelshausen seems to have shared the astrological beliefs of his age; certainly astrological imagery underlies much of the structure of his novels. The significance of the astrological references was presumably obvious to his contemporaries, to the modern reader more than the most immediate meaning requires subtle explication. However, this need not detract from the enjoyment of these lively novels, which contain more than enough human and historical interest to satisfy a reader without awareness of the subtleties of the symbolic structure.

The conjunction of Saturn, Mars and Mercury is the chance meeting in an inn in Strasbourg (though the city is not named) of Simplicissimus, his old comrade, Tearaway, and the author, a young penniless and unemployed clerk, who has recently been conned into writing down the life of Courage, a former lover of both Simplicissimus and Tearaway. He it is who now writes down the story of Tearaways life, though this time he is adequately rewarded for his pains.

The author is a not a self-portrait of Grimmelshausen as far as biographical details are concerned: Grimmelshausen is nearer in age and experience to his first hero, Simplicissimus. The closest we get to a self-reference by Grimmelshausen is the comment by Tearaway, describing one of the more congenial winter quarters he experienced, that he grew as chubby-cheeked as a village mayor in peace-time. Village mayor was one of Grimmelshausens employments after the end of the Thirty Years War.

What the conjunction of the three does allow, apart from some vivid portrait painting, is an assessment of the purpose behind these novels. Simplicissimus insists that everything must relate to an underlying religious/moral purpose. He is even reluctant to tell the other two a funny incident that happened to him because he sees no point in encouraging you to indulge in empty frivolity, which is how I view the excessive laughter the story would inevitably cause. I have no wish to be responsible for other mens sin.

Reminded by the author that he included a lot of funny stories in his autobiography, Simplicissimus replies that that was because otherwise no one would have read the book. He almost regrets this, he says, because now people are reading his book for amusement, like Till Eulenspiegel, rather than to learn from it.

Although this, of course, is Grimmelshausens character speaking, not Grimmelshausen himself, there is certainly a serious moral purpose behind his works. It is to demonstrate the ultimate vanity of earthly things, viewed against eternal truths. The lively and amusing, exciting, mysterious and gory incidents with which the books are filled are thus not just the sugar round the pill, they are essential to the moral thrust: they demonstrate the unsatisfying and unreliable nature of the things of this world, whether concerned with money, success or sex; attachment to them is dangerous to ones eternal soul.

This does not stop the reader (and, one suspects, Grimmelshausen himself) enjoying the stories which carry the moral message. They are related with a vigour and vividness which sometimes makes one wonder whether the moral truths he feels constrained to declare are not merely an excuse for the lively narrative.

There is a further serious intent behind these novels. Grimmelshausen clearly wants to tell how it was in the Thirty Years War. In Simplicissimus and Courage it is seen mainly from below, from the experiences of ordinary soldiers and peasants caught up in the conflict. In the central section of Tearaway, chapters 1020, on the other hand, Tearaways personal account is frequently swallowed up in an overall survey of the warfare within Germany. As he tells his life story, Tearaway keeps getting diverted onto the events of the war as a whole and repeatedly has to come back, or be brought back to his own experiences. This narration of the experiences of the war reflects Grimmelshausens humanism, his sympathy for the sufferings of ordinary people.

These novels are set against the real historical background of the seventeenth-century European conflict known as the Thirty Years War, which Grimmelshausen refers to as the German Wars.

It has been suggested by modern historians that the traditional view of the Thirty Years War as a single coherent conflict between Catholic and Protestant states, which ravaged Germany and left it completely exhausted, is a myth a myth to which Grimmelshausens novels contributed.

In fact, the German Thirty Years War (16181648) was part of a much wider struggle between France and the Habsburg powers (principally Spain and Austria) for hegemony in Europe which broke out intermittently in a number of separate wars during the first half of the seventeenth century. The attempt by the Dutch provinces to establish their independence from Spain was connected with it; it was complicated at times by the struggle of Denmark and Sweden for control of the Baltic area; it was coupled with the attempt by the Holy Roman Emperor to establish his authority over the German states, which was resisted by both Catholic and Protestant sovereigns alike.

One of the purposes of Grimmelshausens Simplician novels is to paint a picture of the historical events, in which he took part himself. However, as suggested above, his main aims are aesthetic and moral, to amuse and to instruct. The German Wars, in which men and women can rapidly rise to great heights of fame and fortune and just as rapidly sink to the depths of poverty and degradation, provide both a wealth of exciting incident and the perfect conditions to demonstrate the vanity of worldly things. Perhaps Grimmelshausens own experiences during the war contributed to his outlook.

His view of the political background to the conflict is, perhaps not surprisingly, simplistic compared with the interpretations of modern historians. For the purposes of understanding Tearaway, it is best to think of the Thirty Years War as a fairly straight-forward conflict between the Protestant and Catholic forces within Germany, fought out in a series of campaigns. The principal contenders on the Catholic side are the empire itself and Bavaria, supported at times by Spain; the principal Protestant states are Weimar and Hesse, supported at times by the French and the Swedes.

Next page