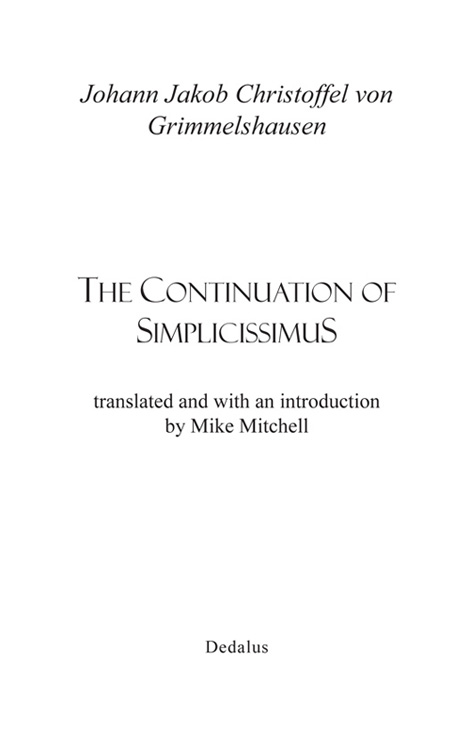

For many years an academic with a special interest in Austrian literature and culture, Mike Mitchell has been a freelance literary translator since 1995.

He has published over eighty translations from German and French, including Gustav Meyrinks five novels and The Dedalus Book of Austrian Fantasy. His translation of Rosendorfers Letters Back to Ancient China won the 1998 Schlegel-Tieck Translation Prize after he had been shortlisted in previous years for his translations of Stephanie by Herbert Rosendorfer and The Golem by Gustav Meyrink.

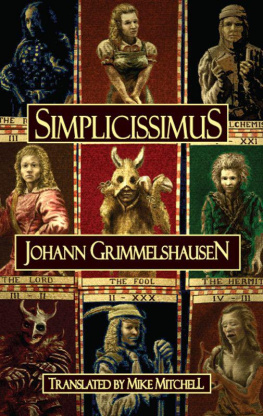

His translations have been shortlisted four times for The Oxford Weidenfeld Translation Prize: Simplicissimus by Johann Grimmelshausen in 1999, The Other Side by Alfred Kubin in 2000, The Bells of Bruges by Georges Rodenbach in 2008 and The Lairds of Cromarty by Jean-Pierre Ohl in 2013.

What is the life of man? Inconstancy its name,

When we think were settled, we must go on again.

O most fickle state! Thinking were at rest

All at once the Fall comes us to molest,

Just as Death comes. Read what such changeful ways

Have done to me in this chronicle of my days,

From which it can be seen that uncertainty

Alone is certain, wherever we may be.

CONTENTS

Grimmelshausen was born in 1622 six years before John Bunyan, with whom there are interesting similarities and differences. Both came from impoverished backgrounds Grimmelshausen put the noble von back in his name once he had become well-known as a writer and managed to get some basic schooling before they were drawn into the wars of the time at an early age: Grimmelshausen at twelve, Bunyan at sixteen, and both confessed to all manner of vice and ungodliness in their youth. Bunyan is best known for works in the allegorical mode and Grimmelshausen, while he is most remembered for his realism, also wrote two moralising works, which are mentioned in the Conclusion, and the The Continuation of Simplicissimus is full of Christian piety, though Grimmelshausen is writing from a Catholic viewpoint, having gone over to the Imperial side during the wars.

In fact, the Continuation could be called Grimmelshausens pilgrims progress. At the end of Simplicissimus the hero withdraws from the world and goes to live as a hermit in the Black Forest. As in Bunyans allegory, Grimmelshausens Continuation also starts with a dream, though a dream of the hero not the author, which is allegorical: he dreams of Hell with the devil and all his minions, who are the personifications of the vices that lead men to Hell. After he wakes he resolves to abandon his solitary life and become a holy pilgrim and makes his way, with various adventures, to Italy, then to Egypt and, captured by Arab robbers, to the Red Sea. It is here that what is the most interesting part of the Continuation starts: having taken passage on a Portuguese merchant ship to return to Europe via Cape Horn, he is shipwrecked on a desert Island almost sixty years before Robinson Crusoe. It is a fruitful island, a veritable paradise, and after the death of his companion, the ships carpenter, he resolves to stay there in his life of solitary piety, even when a Dutch ship, that has been driven off course, offers him a chance of returning home.

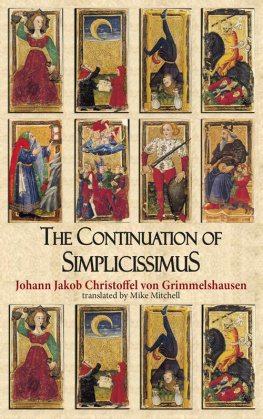

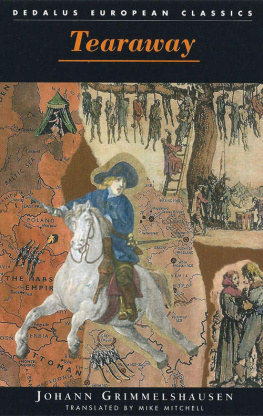

Simplicissimus, published in 1668, though dated 1669, was a great success and Grimmelshausen immediately followed it with a number of other books that are generally referred to as his Simplician Writings: The Continuation was added to the original as the Sixth Book; Courage, Tearaway and four other short works were published over the next few years.

The desert-island episode is presented as a report from the captain of the Dutch ship to the writer German Schleiffheim von Sulsfort of his meeting with the hermit, in which he also claims Simplicissimus gave him an account of his whole life, written by the hermit on palm leaves with ink made from lemon juice and the sap of fernambuco wood. The final Conclusion after this is a note from H. I. C. V. G. (ie Hans Jacob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen) asserting that the book was found among the papers of Samuel Greifsnon vom Hirschfeld after his death and that he was the author of Simplicissimus but had used an anagram of his name on the title page: German Schleifheim von Sulsfort.

This is one final mystification from Grimmelshausen. He published his Simplician writings under the pseudonym of German Schleifheim von Sulsfort (Cornelissens misspelling of Schleiffheim is probably a misprint, or a further mystification). Samuel Greifsnon vom Hirschfeld who is here presented as the real author is not quite an anagram of German Schleifheim von Sulsfort there is a d instead of a t, though they tend to be regarded as interchangeable, since in German final d is pronounced as t. However, if you look at the last three words of Grimmelshausens name above, you will see that German Schleifheim von Sulsfort is a perfect anagram.

If anyone should imagine I am telling the story of my life in order to help people pass the time or, like clowns and buffoons, to make people laugh, then they are very much mistaken! Excessive laughter is something that disgusts me, and anyone who lets the precious, irrevocable hours slip by unused is wasting that divine gift that was given us to work for the salvation of our souls. Why should I encourage such vain foolishness and waste my time giving people entertaining advice to no purpose? As if I didnt know that in so doing I would be participating in other peoples sins. I think myself somewhat too good for such a task, dear reader. So anyone who wants a fool for that should buy two, then he will always be able to make fun of one of them. I may occasionally put on a jesters cap but that is only for the sake of those tender souls who cannot swallow wholesome pills unless they be mixed with plenty of sugar and coated. Not to mention that even the most earnest of men, when they have to read serious writings will tend to put one book down rather than another that brings an occasional smile to their lips.

I may perhaps also be accused of taking a too satirical approach, but I cannot be blamed for that because most people prefer the common vices to be dealt with and castigated in general rather than have their own failings given friendly correction. Thus at the moment Mr Everyman, to whom this my story is addressed, is unfortunately not so fond of the theological pen that I should use it. That is the kind of thing you can see in a huckster or a quack (who call themselves renowned doctors or oculists, claim to be able to cure hernias or the stone and even have parchments with seals attesting that) when they appear in the open market with their merry-andrew or jack-pudding, whose first cry and fantastic capers attract a greater crowd of listeners than the most enthusiastic divine ringing all the bells three times to offer his flock a fruitful, salutary sermon.

However that may be, I hereby publicly declare that it is not my fault if someone should be annoyed because I have decked out my Simplicissimus in the way people demand if you want to teach them something useful. If, however, this or that reader should be content with the husk and ignore the core concealed with in it, they will be happy with an entertaining story. But although that will be far from fulfilling the real intention of this narrative, I am now starting again from where I left off at the end of the Fifth Book.

There the reader will have learnt that I had become a hermit once more and also why that happened; it is, therefore, now appropriate for me to relate what I then did. During the first few months, while it continued to be warm, things went very well. It took no great effort to suppress the urges of the flesh, to which I had been much addicted, for since I was no longer in thrall to Bacchus and Ceres, Venus too refused to come to me. But I was still far from perfect, a thousand temptations assailed me every hour and when I sought to recall my old wanton ways, in order to arouse a feeling of remorse, the pleasures of the flesh that I had enjoyed in this or that place immediately came to mind as well which was neither healthy nor served my spiritual progress. When I now recall the past and think things over, it is clear to me that idleness was my greatest enemy and freedom (because I had no priest to watch over and guide me) the reason why I did not continue in the life I had started out on.

Next page