Table of Contents

Page List

Guide

PRAISE FOR RIVER OF LOST SOULS BY JONATHAN P. THOMPSON

An important work of investigative journalism, especially relevant for those living in the Mountain West.

ALBUQUERQUE JOURNAL

Thompson documents the sacrifice of the entire area with unusual detail, vibrancy, and no small amount of passion, and with a keen eye for the effects on people and other living things. Highly recommended.

CHOICE

Thompson knowledgeably and sensitively addresses ethical questions at the heart of his inquiry, including what it would mean to restore the water system to its pre-colonial state.

PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

Aficionados of Western history, environmentalists, and even general readers will enjoy this cautionary tale that takes an intimate look at the side effects of human industry.

LIBRARY JOURNAL

An elegy of sorts for a beloved natural area with a long history of human exploitation.

FOREWORD REVIEWS

The reader will revel in the beauty of the Colorado landscape while recoiling from descriptions of cruelty towards the Native Americans and the horrors of acid mine drainage.

BOOKLIST

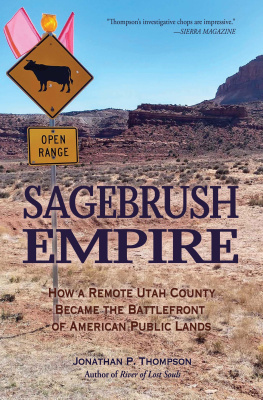

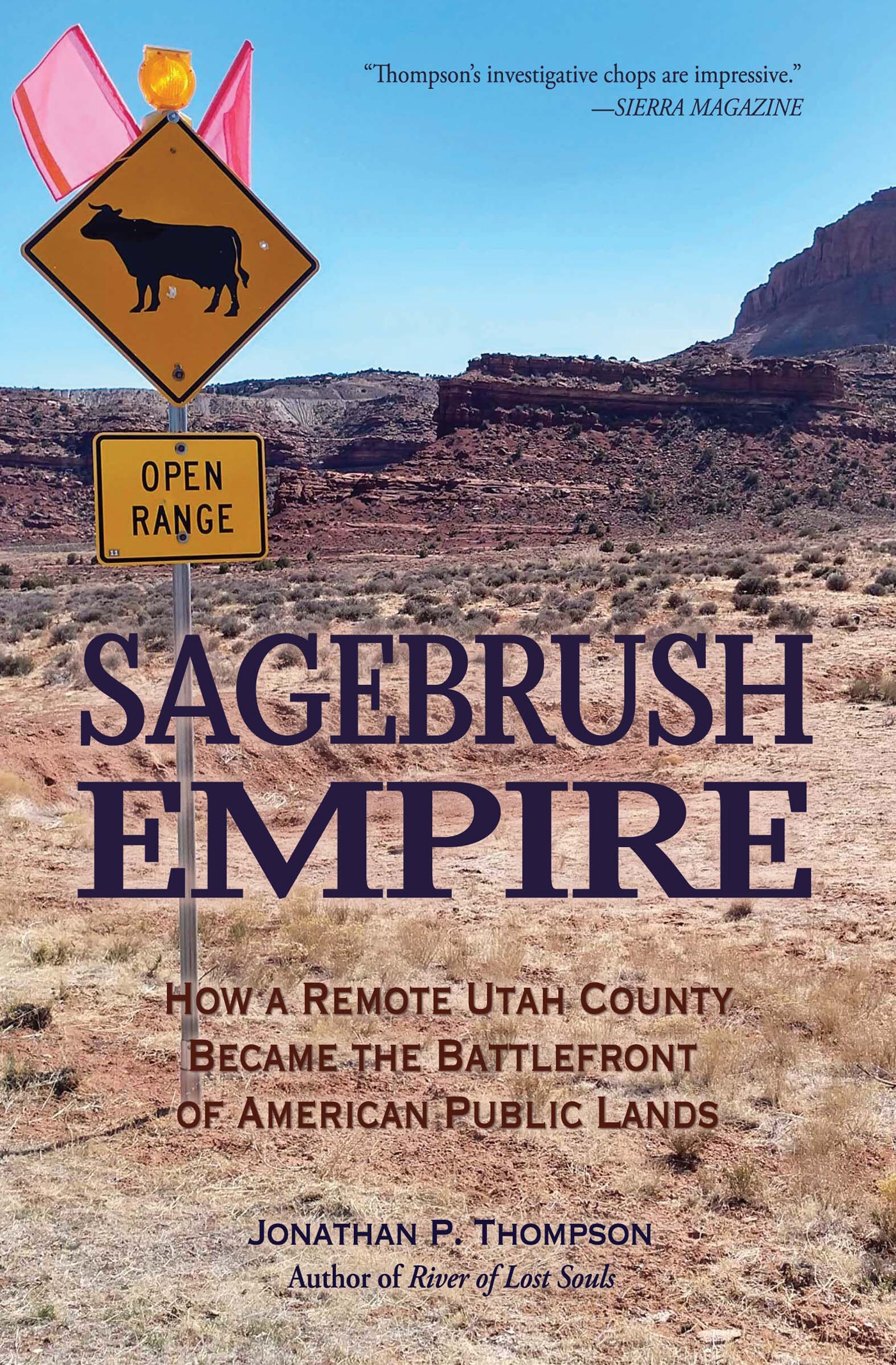

SAGEBRUSH EMPIRE

SAGEBRUSH EMPIRE

HOW A REMOTE UTAH COUNTY BECAME THE BATTLEFRONT OF AMERICAN PUBLIC LANDS

JONATHAN P. THOMPSON

First Torrey House Press Edition, August 2021

Copyright 2021 by Jonathan P. Thompson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any form or by any means without the written consent of the publisher.

Published by Torrey House Press

Salt Lake City, Utah

www.torreyhouse.org

International Standard Book Number: 978-1-948814-44-7

E-book ISBN: 978-1-948814-45-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020946734

Cover photo by Kirsten Johanna Allen

Cover design by Kathleen Metcalf

Interior design by Rachel Leigh Buck-Cockayne

Distributed to the trade by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

Torrey House Press offices in Salt Lake City sit on the homelands of Ute, Goshute, Shoshone, and Paiute nations. Offices in Torrey are on the homelands of Southern Paiute, Ute, and Navajo nations.

This book is dedicated to Wendy, Lydia, and Elena; to my parents, who introduced me to the marvels of the canyon country;

and to all of the people who have accompanied me on zany adventures among the sagebrush and sandstone.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

GATEGATE

A LITTLE HAND-PAINTED SIGN IN THE STYLE OF THOSE clichs that you can pick up for a buck or two in the sale bin at TJ Maxx hangs slightly crooked on the wall of Mark Franklin and Rose Chilcoats living room above a window that looks out at their Durango, Colorado, neighborhood. It reads: Live like someone left the gate open. Without context, it makes zero sense. And once you know the story behind it, about how a seemingly insignificant act would throw the couple into an interminable legal quagmire that still hadnt ended three years later, you might wonder why the hell these people have the sign up at all.

The geographical context in which the act took place is the Valley of the Gods. Like the sign, the name of this place doesnt equate without context. The landscape in this part of southeastern Utah appears mostly flat, broken only by a few landforms sticking up in the distance and bounded on one side by a band of cliffs made up of various hues of pink and beige. From the valley the cliffs look unnaturally small, as do the landforms, perhaps an optical illusion resulting from the vastness of the flats and the sky. It is only when you are atop that band of cliffs, otherwise known as the south edge of Cedar Mesa, that you can really see the Valley of the Gods. The illusion from below is shattered and the sheer scale of the valley becomes clear, particularly on stormy days, when clouds rush across the sky like galleons atop a sea the color of dried blood and light plays upon the Kodachrome serpent of earth and stone known as the Raplee Anticline.

Chilcoat and Franklin were in the Valley of the Gods in April 2017 when their lives took a surreal turn, the consequences of which were still playing out three years later, when I sat down with them in their home in Durango to talk about it. Or, rather, we would talk around that fateful day, since they had yet to give depositions in the most recent phase of the legal tussle and therefore couldnt talk about the case itself (details about the case itself come from court documents and exhibits, including depositions from all parties involved, and post-deposition interviews with Chilcoat and Franklin).

Our interview took place in the early days of the coronavirus, when toilet paper and hand sanitizer were hard to find, but businesses were still open, no one was wearing a mask, and some folks still shook hands in greeting. We had no clue what was coming, or that had we waited another week, the in-person interview would have been relegated to our computer screens. As it was, when I entered their house they immediately scooted some hand sanitizer in my direction and we awkwardly elbow-bumped rather than shake hands or hug. Chilcoat was in a wheelchair, a crocheted blanket over her legs, thanks to a brutal ski accident, but her powerful presence was undimmed. Franklin is shorter than Chilcoat, with a white goatee and lively eyes behind square-rimmed glasses.

Franklins family goes back a few generations in the region. His great-grandparents landed in Leadville, Colorado, during that citys mining heyday, and then, during the Dust Bowl, his family moved from the small burg of Bethune, Colorado, to Gallup, New Mexico. Franklin was born in Albuquerque and spent a lot of time hiking and camping and river running in Utah. Ive been going to [San Juan County] since there was only one paved road into Bluff and the San Juan River didnt require permits, he said. After graduating from the University of New Mexico with a degree in biology, Franklin started fighting wildfires before segueing into a variety of other government work, mostly with land management agencies.

Although Chilcoat grew up in the Maryland suburbs, her parents were adamant about getting her out into the natural world as often as possible, hiking and camping up and down the East Coast. Youre imprinted at an early age, she said. She worked for the Youth Conservation Corps and went to college at Virginia Tech, where she majored in horticulture and minored in environmental studies. In the early 1980s she moved to Durango to take a summer job with the San Juan National Forest doing cadastral surveys and first saw southeastern Utahs canyon country during that time when she went on a rafting trip on the San Juan River.

Soon thereafter, Franklin met Chilcoat at Lees Ferry on the Colorado River as they embarked on a Grand Canyon rafting trip. Together, in Franklins telling, they were nomads following jobs and experiencing diverse public lands. Chilcoat worked as a biological science technician in forest planning and in various park ranger positions at Mesa Verde National Park, Rocky Mountain National Park, Bryce Canyon National Park, and at Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area, before heading to Anchorage, Alaska, to work for the Park Service there. Franklin fought fires, managed a visitor center, and worked on the Exxon oil spill in Valdez, Alaska. The two worked side by side as raft guides in Big Bend National Park in Texas.