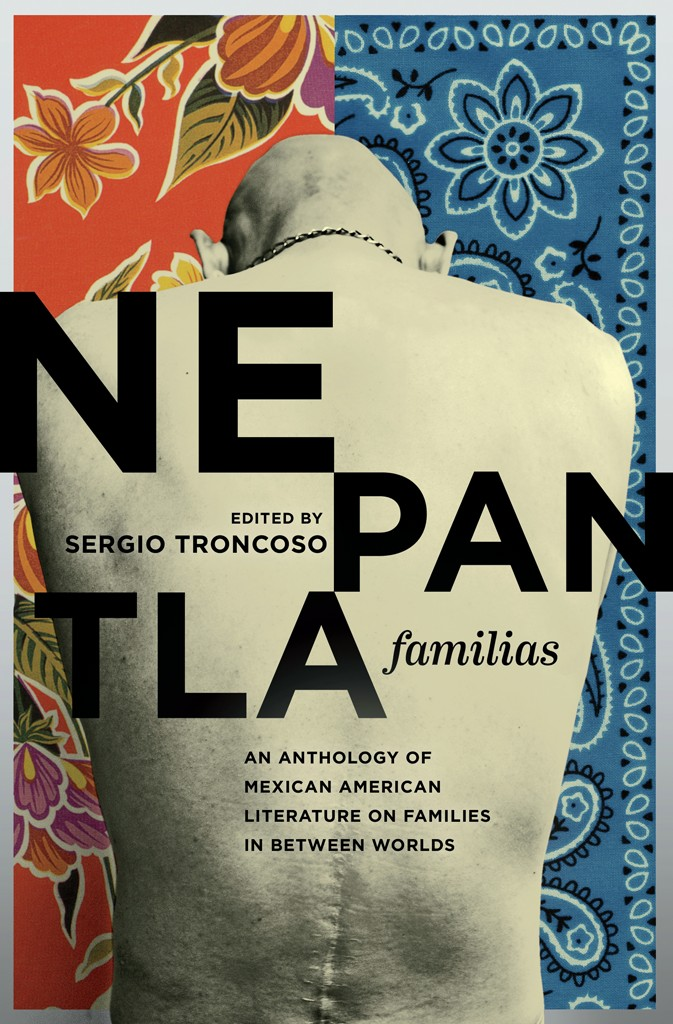

Nepantla Familias

The Wittliff Collections

Wittliff Collections Literary Series

Steven L. Davis, General Editor

NEPANTLA FAMILIAS

An Anthology of Mexican American Literature on Families in between Worlds

Edited by Sergio Troncoso

Texas A&M University Press

College Station

Copyright 2021 by Texas A&M University Press

All rights reserved

First edition

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Binding materials have been chosen for durability.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Troncoso, Sergio, 1961 editor.

Title: Nepantla familias : an anthology of Mexican American literature on families in between worlds / edited by Sergio Troncoso.

Other titles: Wittliff Collections literary series.

Description: First edition. | College Station : Texas A&M University Press, [2021] | Series: Wittliff Collections literary series | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020052162 | ISBN 9781623499631 (cloth) | ISBN 9781623499648 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Mexican AmericansEthnic identity. | Mexican

AmericansCultural assimilation. | Mexican American families. | Mexican

American familiesIn literature. | Mexican Americans in literature. | Group identity in literature. | Mexican-American Border RegionIn literature. | LCGFT: Essays. | Poetry. | Short stories.

Classification: LCC E184.M5 N35 2021 | DDC 973/.046872dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/202005216

SOURCE CREDITS

All the Pretty Ponies by Oscar Csares first appeared in Texas Monthly, 2014. Reprinted by permission.

Mujeres Matadas by Daniel Chacn first appeared in Hotel Jurez: Stories, Rooms, and Loops, Arte Pblico Press, 2012. Reprinted by permission of Arte Pblico PressUniversity of Houston.

An excerpt from Losing My Mother Tongue by Reyna Grande was previously published on LitHub.com, 2019.

Self Portrait in the Year of the Dog by Deborah Paredez first appeared in Year of the Dog, BOA Editions, 2020. Reprinted by permission of The Permissions Company, LLC on behalf of BOA Editions, Ltd.

Mundo Means World by Octavio Solis first appeared in Catamaran Literary Reader, 2016. Reprinted by permission.

Life as Crossing Borders by Sergio Troncoso first appeared in New Letters, Vol. 85, No. 4, 2019. Reprinted by permission.

Contents

by Sergio Troncoso

Nepantla Familias

Introduction

As a child in the Ysleta neighborhood about a quarter of a mile from the USMexico border, I had a strange recurring dream: I would be suspended in the clouds or fog, on a beam, gently falling into oblivion to one side and then falling to the other. I would never feel any pain or terror, and I would never know what happened after I fell to one side of the beam or the other. In the dream, it was the falling that mattered, somehow, the movement, and it was sitting on the beam for a few seconds before inevitably I would sway and fall to one side or the other.

Over the years, after I left childhood and El Paso, Texas, after I left the border and returned to it, I would interpret this dream of the middle ground in many ways. Living between Spanish and English. Being Mexican yet also American. Choosing values I inherited from my parents while also choosing values I created for myself. Living in many worlds in a single daythe worlds of the past and the present, the worlds of cities and rural areas, and the worlds of different languages and cultures. I believed the dream image even applied to my feeling of being in between the outsider who is ignored or attacked and the native who inherently belongs in the United States. Lately, as I have gotten older, I think about this dream in another way, as living on the border between life and death, with the many questions to be answered about the undiscovered country all of us will visit, but also about how those very questions change the life I live today. Strangely, falling to one side helps you to understand your falling to the other side in the next instance.

So the middle ground or borderland that defines nepantla has been with me, in one way or another, all my life, and the essays, poems, and short stories in this anthology reflect the diversity and variety of experiences that might explain, reveal, and mysteriously explore this liminal land that is so essential to the Mexican American experience, particularly within families. Because it is through our families that we live nepantla, that we negotiate it, that we have questions about our identity and choices, that we are convinced to fall one way or another, or even to balance perpetually between many different worlds. Through our families, we understand better the other side, even if we perhaps fall more to a side different from our ancestors.

This Mexican American experience of living between two worlds has beenand will forever beessential and important to the United States for at least three reasons. Of course, the first reason is the proximity of Mexico to the United States and the growing numbers of Mexican Americans who are citizens of the United States. But the ability of at least some Mexican Americans to go easily back and forth, between countries and languages, gives this first reason a continuing vitality that does not exist for other immigrants to the United States. And that many nonMexican Americans not only regularly travel to visit our southern neighbor but also live and retire in Mexico has created another version of nepantla that in a way dovetails the Mexican American nepantla of this anthology.

The second reason Mexican American nepantla will remain at the forefront of our culture and society is what it reveals: the wounds of our history. The wounds of Mexicans feeling like outsiders in a land that was once theirs. The wounds of leaving Mexico for opportunity in the United States and then often feeling a step behind in language, knowledge, and power. The wounds of leaving home for some place better that you also want to make into a home. Some of these wounds heal permanently, and some heal for a moment, only to be ripped open again later. Many of these wounds may haunt us even as we appear polished, accomplished, and well integrated into our communities in the United States. These wounds in many ways define us, and should define us, not only for the pain they have caused us, but also for what we have endured and overcome. In moments of peace, these wounds may even be a source of our tragicomedy and laughter.

That brings us to the third reason why I believe nepantla will remain a vital experience in the United States: as much as nepantla helps to understand Mexican Americans, living in a middle groundwith its uncertainty and questioning of the selfis also a deeply universal experience. But to appreciate this, a reader has to open these pages, experience these essays and poems and short stories, and cross her own borders. Toward empathy. What this reader will discover is new possibilities for understanding the Mexican American experience of nepantla. Most of the literary work in this anthology is appearing for the first time anywhere. Of the thirty literary works in this book, only five have been previously published as of this writing.

That is my hope, at least, as the editor. Anyone who has left their home and tried to find a new one in a strange placeat times welcoming and at times hostilethey should find themselves in these pages. Anyone who has felt stymied by ancestors and their demands, yet also emboldened by their sacrifices and forgotten valuesthey should find themselves in these pages. Anyone who has forged a self from pieces of many worlds, to fit and not fit in a new home, who has balanced on many beams to understand different sidesyes, they should find themselves in these pages. Anyone who has loved another from a different worldthey should recognize a version of themselves in these pages. And anyone who has crossed any border to create who they are, rather than to take who they are for granted, rather than to assume a place belongs to themand suffered the consequences for itthey will find their fellow travelers, their kindred spirits, in these pages.