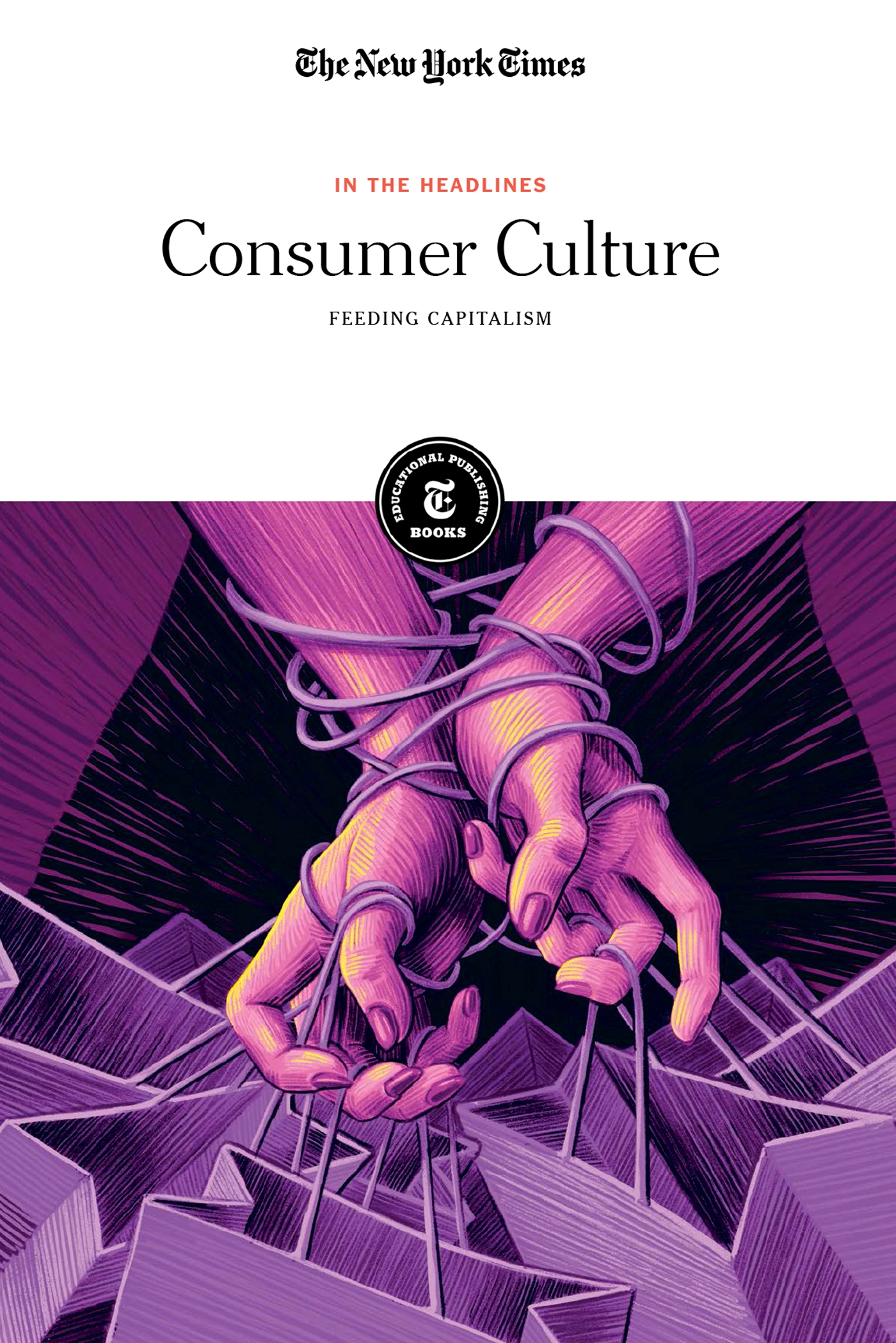

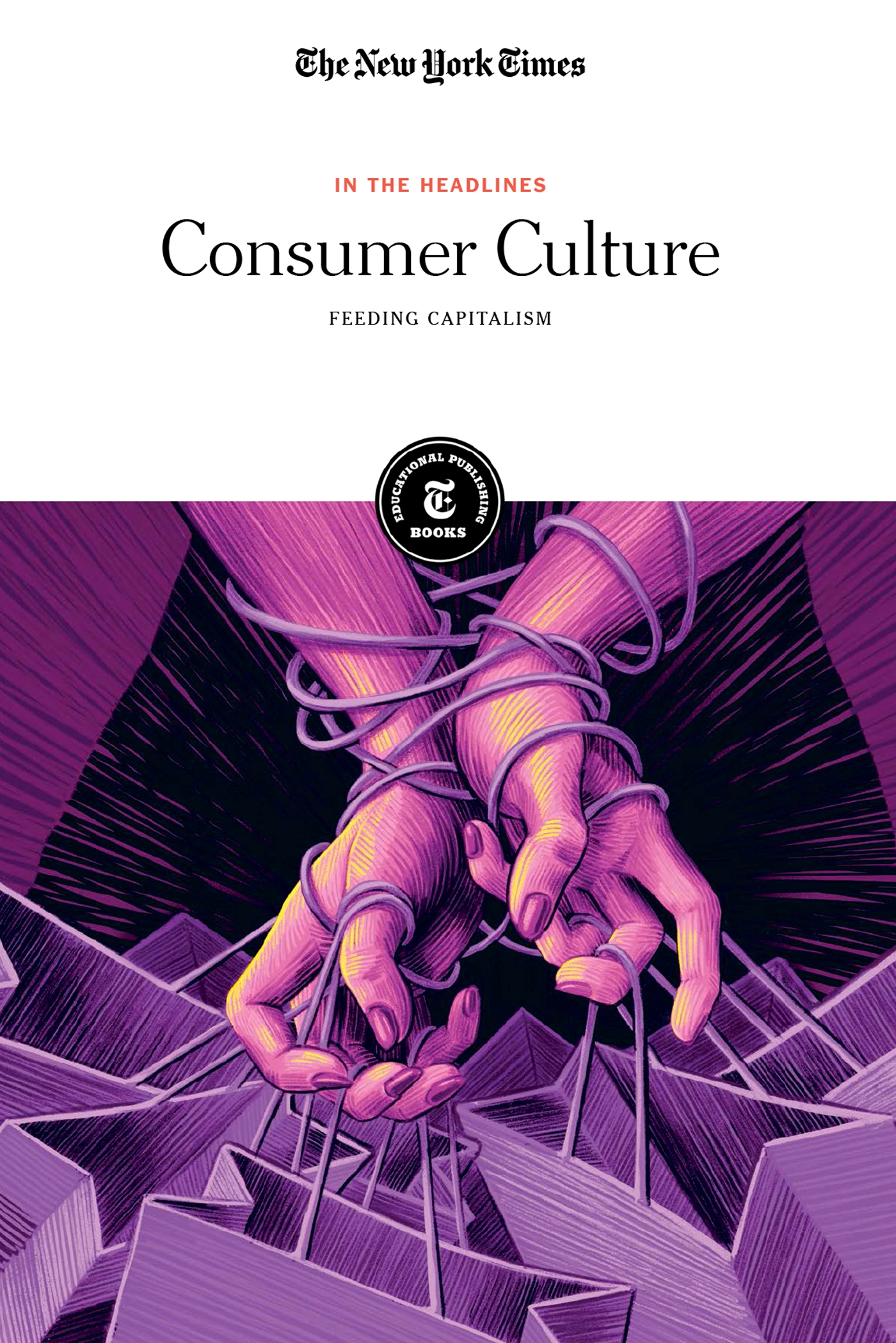

Published in 2020 by New York Times Educational Publishing

in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2020 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2020 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Caroline Que: Editorial Director, Book Development

Phyllis Collazo: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Julia Bosson: Editor

Greg Tucker: Creative Director

Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Consumer culture: feeding capitalism / edited by the New York Times editorial staff.

Description: New York: The New York Times Educational Publishing, 2020. | Series: In the headlines | Includes glossary and index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781642823547 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642823530 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642823554 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Consumer behaviorJuvenile literature. | Consumption (Economics)Juvenile literature. | Consumer goodsJuvenile literature. | Popular culture Marketing Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC HF5415.32 C66 2020 | DDC 658.8342dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

On the cover: Companies try to lock people into buying their products without comparison shopping; Brian Britigan/The New York Times.

Contents

Introduction

IN 1939, PRESIDENT Franklin D. Roosevelt announced that Thanksgiving would be celebrated a week earlier that year. The calendar had the holiday falling on the last day of November, leading retailers to claim they would not have enough time before Christmas to hold their sales. Roosevelt listened.

This decision demonstrated the unique link between American culture and consumerism. Each holiday celebrated in America has its connections to material goods of some kind: Thanksgiving has Black Friday; Valentines Day its Hallmark cards and heart-shaped boxes of chocolate; Christmas and the gifts that accompany it. America is the home of Amazon, big box stores and, of course, the shopping mall, the site of so many movies and television programs. No newspaper or magazine in America exists without a large advertising section. Culturally speaking, consumerism is as American as apple pie (which can be purchased at just about every grocery store nationwide).

The articles in this collection seek to untangle and examine particular aspects of consumer culture, considering both its workings as well as its implications. In these chapters, journalists reckon with the ways in which consumerism has become a pernicious and enduring aspect of American culture as well as the ways it has helped boost the economy. They explore how consumerism impacts psychology and the various methods retailers use in order to predict and capitalize on consumer behaviors. In several articles, journalists explore the relationship between supply and demand as merchandisers play a cat-and-mouse-game with consumers, attempting to predict trends even as consumers dictate the flow of capital.

MICHAEL WARAKSA

As technology has evolved, so too have consumer patterns. Over the last twenty years, mom-and-pop stores were largely eradicated by the rise of centralized shopping malls and big box stores such as Walmart and Target. More recently, the unprecedented rise of Amazon, which has transformed from a book merchandiser to an online behemoth that sells everything from toilet paper to on-demand television, has changed the game, leaving many shopping malls ghost towns and major retail chains struggling to stay afloat.

There has also been a series of public exhortations to make consumerism a more conscious aspect of American life. As the link between consumption and climate change has become more clear, there has been a rise in the zero-waste movement, which attempts to eliminate waste and to only use products that are recyclable. And as Americans have seen money and power consolidated in the hands of corporations and executives, there have been moves to help protect the individual consumer, including the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which was created in 2011 under a plan by Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren.

As buying largely shifts online, new models of retail are being created. In some places, while larger department stores have closed, small businesses have cropped up, offering a more curated consumer experience. And now that our phones have become the primary medium through which we engage with the world around us, it stands to reason that they will impact the future of consumerism in America.

The buying and selling of data in order to create more and more targeted advertisements has become the financial backbone of the tech world. Facebook and Google make their fortunes by delivering promotions directly intended to attract their users. Soon, geotracking will be used to encourage consumers to visit stores as they pass them. As the economy evolves, what the tech companies need is for consumers to continue with what they do best: consume.

CHAPTER 1

The Culture of Consumerism

Over the course of the 20th century, consumerism has become an integral part of American culture. The production of and mindset behind the purchasing of material goods is so deeply ingrained that it constitutes an identity. The articles in this section explore the various manifestations of consumer culture, ranging from individual acquisition habits to those great beacons of consumption, shopping malls.

In Buying We Trust: The Foundation of U.S. Consumerism Was Laid in the 18th Century

BY PAUL LEWIS | MAY 30, 1998

A PENNY SAVED is a penny earned and Benjamin Franklins other homespun exhortations may stir nostalgia for an earlier age when habits of frugality and thrift are thought to have been more deeply ingrained in the American character.

Yet some scholars have questioned whether those early colonial Americans wouldnt have been almost as devoted to, say, the Home Shopping Network as their modern counterparts are.

Recent scholarship has convincingly demolished the notion of a sudden and late revolution that transformed America into a nation of consumers, writes Daniel Horowitz in The Morality of Spending, a 1992 history of consumer attitudes. Carole Shammas, a historian at the University of California at Riverside, agrees: The foundations of American consumerism were laid in the 18th century, when large quantities of imported manufactured goods from England started to circulate in the 13 colonies.

Indeed, the origins of colonial Americas relationship with thrift and consumerism are complicated. While there was certainly a reverence for the values associated with thrift, there was also a vital and active consumerism.

Yet until recently, only the thrift side of the equation was emphasized. It was assumed that thrift was an article of faith for Americas early Protestant dissenters, Puritans, Baptists, Methodists, Quakers and the like. And indeed, they believed that God had called man to occupy a particular place in this world, and therefore he must fulfill the obligations imposed on him by his calling. This implied careful husbandry of possessions because they came from God.

As David Fischer, a historian at Brandeis University, points out, as late as 1775 no less than three-quarters of the churches in the colonies belonged to dissenting Protestant faiths that believed every man had such a sacred calling.

Next page