THE QUOTABLE

Oscar

Wilde

By Sheridan Morley

Biography by

Teresa Bonaddio

RUNNING PRESS

PHILADELPHIA LONDON

A Running Press Miniature Edition

2013 by Running Press

All rights reserved under the Pan-American and International Copyright

Conventions

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without written permission from the publisher.

The proprietary trade dress, including the size and format of this Running Press Miniature Edition is the property of Running Press. It may not be used or reproduced without the express written permission of Running Press.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Digit on the right indicates the number of this printing

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012954266

ISBN 978-0-7624-5328-3

Running Press Book Publishers

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

2300 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19103-4371

Visit us on the web!

www.runningpress.com

Contents

by Sheridan Morley

G iven that this celebration of the Wilde wit appears more than a century after his death in Paris in 1900 (its the wallpaper or me, one of us has to go), it may seem a little curious of me to claim that I owe Oscar my life; but that is the literal truth. In the late 1930s, my father, Robert Morley, was the first actor to play Wilde on the London stage, and thirty years later he was also the first actor to play him on film. But it was the initial run of Oscar Wilde on Broadway that first established my fathers stardom. Opposite him in the original cast (as Lord Alfred Douglas) was a young English actor called John Buckmaster, the son of Gladys Cooper, and like his mother intent on a stage career.

By the time the Broadway run of the play ended, it was clear that there was to be a war in Europe. Buckmaster decided that rather than return home, he would stay in the United States and, if necessary, fight with the Canadian rather than the British army. He did however have a sister Joan, still in London, and asked my father if he would carry some presents home to her. My father duly returned to England, looked up Buckmasters sister, took her the gifts, and subsequently married her. I was born a couple of years after that.

So Oscar has always been kind of central to my life. Although I cannot claim to be a Wilde scholar, I was once asked to write his biography. I was just about to decline, when by chance a publisher showed me a remarkable cache of photographs taken at the Paris Exhibition of 1900. Until then, conventional wisdom had it that Oscar spent the last few months of this life in deep Parisian penury before dying of neglect; but there in these photographs, taken six months before his death, is a wonderfully dressed Wilde with a showgirl on each arm and a heavy gold watch-chain, proudly posing beneath the brand new Eiffel Tower. So although his actual death was clearly lonely and agonizing, it is good to know that a few months earlier the good old Oscar was still very much in evidence.

In collecting just a few of his thousands of epigrams, it occurs to me that the master playwright lived and died just a bit too early. Not only would he have made a brilliant television talk show host, but the speed and variety of his wit would have guaranteed him a column in any periodical in the world. He died at the very start of the century in which he would have been so much happier, better understood, and so much more gainfully employed. If Oscar Wilde was a martyr to anything, it was surely to the kind of bad timing he would never have allowed in any of his plays.

You do anything in the world to gain a reputation. As soon as you have one, you seem to want to throw it away. It is silly of you, for there is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.

The Picture of Dorian Gray

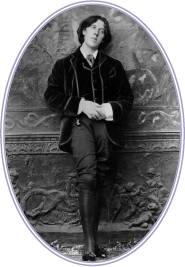

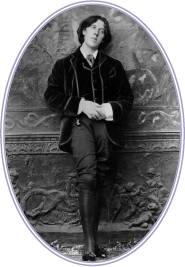

O scar Wilde was not just an Irish writer of poetry, novels, and playshis reputation was famed worldwide, some might even say he was notorious. Arguably one of the most quotable artists of the nineteenth century, he spoke profoundly and wittily not only in his creative works, but also in life. One did not have to be a member of his family or a close friend to know that he was an engaging and entertaining storyteller. He made it known.

Born on October 16, 1854 in Dublin, Ireland, he was christened Oscar Fingal OFlahertie Wills Wilde. With the number of names he acquired, he joked that, As one becomes famous, one sheds some of them, just as a balloonist, when rising higher sheds unnecessary ballast. All but two have already been thrown overboard. Soon I shall discard another and be known simply as The Wilde or The Oscar. In the line of family, he was a middle child, with one older brother (William Willie Charles Kingsbury Wilde) and one younger sister (Isola Francesca Emily Wilde). Over time, they were what society would call an unconventional family, riddled with legends of scandal.

Oscars father, William Wilde, worked as a doctor, specializing in the treatment of ears and eyes. His mother, Jane Frances Agnes (born Jane Elgee) penned her way through life. Pseudonymously known as Speranza, she wrote poetry for The Nation. As upper-middle class parents, they exposed Oscar to a variety of interesting individuals who were welcomed into their home. Those guests ranged from doctors to lawyers, artists to literati, and academics to foreign travelers. Unlike more traditional parents of the time, Jane and William were said to encourage Oscar to sit at the table with them and listen to the adult conversations. As he grew up, this experience influenced his future proficiency at mingling with a multitude of people.

Aside from family, education undoubtedly shaped Oscars intellect. The family lived near Trinity College and Oscar was tutored privately by a German governess before going on to board at Portora Royal School at Enniskillen. At his time of study there, his sister Isola passed away from fever. Shortly after, he left Portora by way of the Royal School Scholarship to Trinity College (18711874). From 1874 to 1878 he attended Oxford College in London. Toward the end of his life, in prison, he wrote, The two great turning points of my life were when my father sent me to Oxford, and when society sent me to prison.

Oscar Wilde had what it took to make it in London, except one thing: money. In his play A Woman of No Importance, which premiered in 1893, he seemed to use his art as therapy, infusing the dialogue with his life thoughts. To get into the best society, nowadays, one has either to feed people, amuse people, or shock peoplethat is all. A man who can dominate a London dinner-table can dominate the world. And that he didamuse people, shock people, and dominate dinner tables. For him, money didnt bring notoriety; his personality did.

In the 1880s, Wilde tried his hand at different ventures and exercised his talents for making money. His first book, called

![Wilde Oscar - The secret life of Oscar Wilde: [an intimate biography]](/uploads/posts/book/228457/thumbs/wilde-oscar-the-secret-life-of-oscar-wilde-an.jpg)