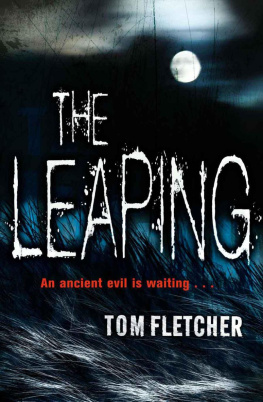

THE LEAPING

Tom Fletcher was born in 1984 in Worcester, and has since lived in Cheshire, Cumbria, Wakefield, and Leeds. He is married and currently lives in Manchester. He loves autumn, video games, bad films, mountains, the sea and (obviously) books. He loves cats too, but cant currently have one because he is a tenant. He used to play the drums and hopes to pick it up again soon, and is also trying to learn to play guitar, but thats taking a while. He is the author of several short stories, published in the anthologies Parenthesis (Comma Press) and Before the Rain (Flax). His short story The Safe Children was published as a chapbook by Nightjar Press. He blogs at www.fell-house.wordpress.com.

THE LEAPING

Tom Fletcher

First published in 2010 by

Quercus

21 Bloomsbury Square

London

WC1A 2NS

Copyright 2010 by Tom Fletcher

The moral right of Tom Fletcher to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Lines from Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening from The Poetry of Robert Frost , edited by Edward Connery Lathem, published by Jonathan Cape. Reprinted by permission of The Random House Group Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 84916 135 0

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places and events are either the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset by Ellipsis Books Limited, Glasgow

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

For Beth

PROLOGUE

E RIN

The wind wakes me up in the early hours and I confuse the present with a memory; one summer, years ago, we were kept awake by the wind, because it was really strong, powerful. I remember hearing the slates coming off the roof and imagining them whipping through the air like huge lethal crows, and hoping that they wouldnt land on either of my parents. I dont know why they would have been outside. Maybe it was that fear that kept me awake, not the wind. In the morning, when it got light, we found that the whole of the village had been covered in this red, dusty film, making windows and windscreens dirty and thick. It was sand from the Sahara blown over by some high, snaking wind, high above the clouds and the cities that I used to believe were in the clouds, and oh, our white car. The car wash at the garage, all that sand, all that sand from the hot, dry, red desert, down the drain at the petrol station. My mum said that it had happened once before, when she was very young, and there had been this other time, she said, when she woke up one night, and the sky was dark red. The sun hadnt come up, and it was the middle of the night, but the sky was brick-red, cold, dead, barren, and she had never known what that was, and her parents hadnt been able to explain it, and it had scared her. She had been four or five or something, and her hair was a huge big knotty ball around her head. Shed said it scared her, since she was only a kid, but I think it would have scared anybody.

My bedroom is dark still, and I should get back to sleep because Im in work at nine. Its only when I close my eyes again and listen to the wind that I remember I was dreaming. I was dreaming about a red sky. The way things can connect in your head without you knowing about it it makes me shudder. I was dreaming about a place with no people, like a desert or the moon or something. And the sky was all red. A deep red, like a sunset, but more complete. Just completely red. And there was somebody walking towards me. Some sort of giant, huge he was, gradually blocking out the sky as he got nearer, but he was only ever a black silhouette. His knees were bent the wrong way.

Mum said that when I was little I would ask what was at the end of the sky. And shed say space, the universe, and Id ask what was at the end of the universe, and shed say nothing, nothing, and Id say, but whats actually there ? And shed say OK, OK then, Erin, OK, a big brick wall. A big brick wall. A big red brick-red wall.

Is there a door, Id say.

No, shed say.

No door.

PART ONE

J ACK

Ice Bar was quite full, but we managed to get standing room near the tiny, comfy bit with the sofas separated from the rest of the club by a pair of heavy curtains so that when the sofas became free we could just hop on. The walls and floor were brown and the sofas were cream and there were low, black tables with little tea-lights on each one and the music was too bland even for me to be able to say what genre it was.

I hope hes OK, Erin said. He said his mother sounded a bit fretful on the phone.

Sure hell be fine, Graham said. Francis thinks everybodys down all the time. He always thinks theres something wrong.

But still, Erin said. I hope theyre all OK. She drew deeply on the straw that protruded from her Long Island Iced Tea and her large, green eyes scanned the small, dark room for Taylor. Wheres Taylor? she asked.

Hell be here soon, I said. He wasnt finishing work until eleven.

Hell be properly fucking some monumentally screwed-up fresher in her Playboy shit-pit of a bedroom, Graham said. I bet.

Shut up, Graham, Erin said. Youre such a rapist.

Its hardly going to be a fresher, I said. I mean, were not even at university any more.

Graham just shrugged and downed his Stella, spilling a little into his massive blond beard. Just a joke, he said, and looked around hungrily.

Taylor told me he likes you, Erin, I said.

Yeah, but I want him to tell me , she said.

You know Taylor, I said. Hes not the most forthcoming of people. Why dont you tell him that you like him?

Oh, I dont know! She smiled and laughed. Her face was surrounded by thick, red curls. Her skin was pale and smooth and her high cheeks were lightly freckled.

Taylor is lucky, I thought, hes a lucky boy or, rather, a lucky man, but I didnt say it. He probably knew it, but was one of those people who pretty much kept his thoughts to himself.

This is shit, Graham said. What are we doing? Whats the plan? Are we going to go anywhere good?

Were waiting for Taylor, I said. Remember?

Oh yeah, he said. Hey! Those dickheads are going. Quick get the sofas!

Have you taken anything tonight, Graham? I asked. You seem jumpy.

*

Just the usual, he said. Just a pill.

Taylor was tall and dark-haired and thin-faced and looked a little bit like a young Richard E. Grant, which Erin liked, and thats what mattered, I suppose. He emerged from between the curtains and, spotting us immediately, made his way over to us, picking his way through a maze of soft leather beanbags and amorous couples.

Evening, he said. You all OK?

Yes, thank you, Erin said, quickly.

Ill be better once Ive got about ten more drinks inside me, Graham said. Either that or some fit girls finger.

Im all right, thank you, I said. How was work?

You know better than to ask that, Taylor said.

We all worked at the same place. A monolithic building that was a multi-storey call centre somewhere near the middle of Manchester, comprising of floor upon floor of old, unreliable computers, broken spirits and bowed heads connected via black, curly wires to telephones that crouched like bulbous insects on the dirty desks, the humming of tonnes of electrical equipment, the frustration of bad maths, the pure panic of not knowing all the answers all the time, right now, come on, what are they paying you for, you been to school or what? The slimish scorn of the nation, dripping through earpieces and trickling into our open ears like warm, lumpy milk. You heard people say all kinds of things. The building towered up into the greenish city sky and burrowed down, it seemed like, burrowed down and down all the way to hell. There was something of the hell-wain about it. The hell-wain was a vehicle, an old coach that reputedly rattled around transporting the souls of the dead. The call centre had that kind of lifeless, limbo-esque feeling to it. The place was open twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, and we all worked varying shifts.

Next page