The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

So you love unicorns

Why wouldnt you? With their rainbow manes and glittery hooves, unicorn magic and adorable friendship dramas, unicorns are some of the friendliest mythical creatures. They prance through cartoons and picture books and make some of the most adorable stuffed animals.

Or is that not the kind of unicorn you were thinking of?

Maybe you had something a little more majestic in mind: an elegant equine galloping through a meadow, its pristine white coat shimmering in the sunlight, long mane and tail streaming behind. What could be more romantic than the unicorn of legenda wild, magical creature that cannot be tamed?

Truth be told, theyre both pretty hard to resist. But which one is the real unicorn?

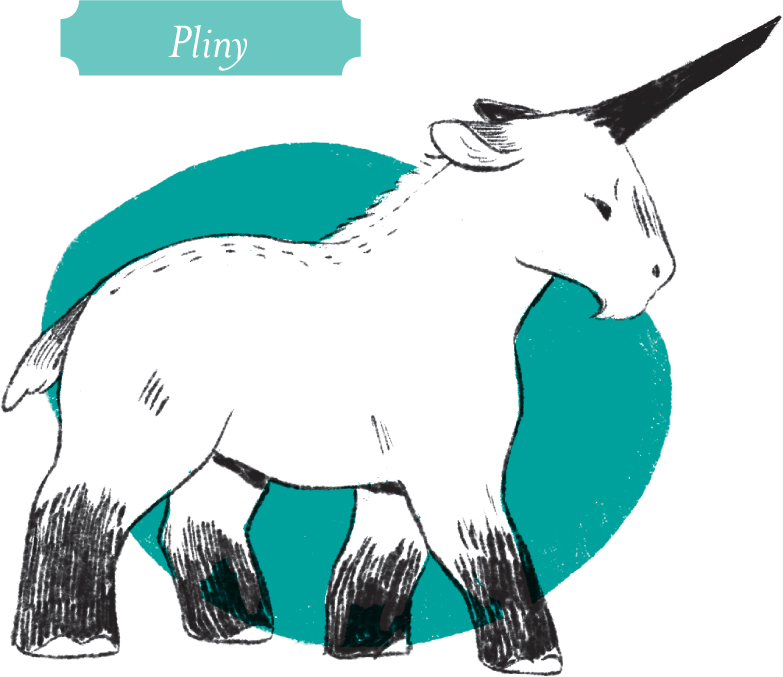

They both are. Each is the unicorn of its time and place, variations on a creature that may have changed more than any other over the past two thousand years. Centuries ago, unicorns were pocket-sized petslittle lap goats with beards and cloven hooves that perched on ladies laps in paintings. Before that, they were murderous, feral animals whose eyes glowed red. Like any good mythical beast, unicorns reflect the hopes and fears of their storytellers. Sometimes they also boogie down and shovel snow.

Whichever kind of unicorn you prefer, theres a world full of adventures and lore out there just waiting for you to go looking for it.

You can make your own unicorn magic, whether its real or imagined, if youre willing to go for it. I hope this book will start you on your way.

Your unicorn guide,

How long have there been unicorns? Possibly as long as there have been humans to tell stories about them.

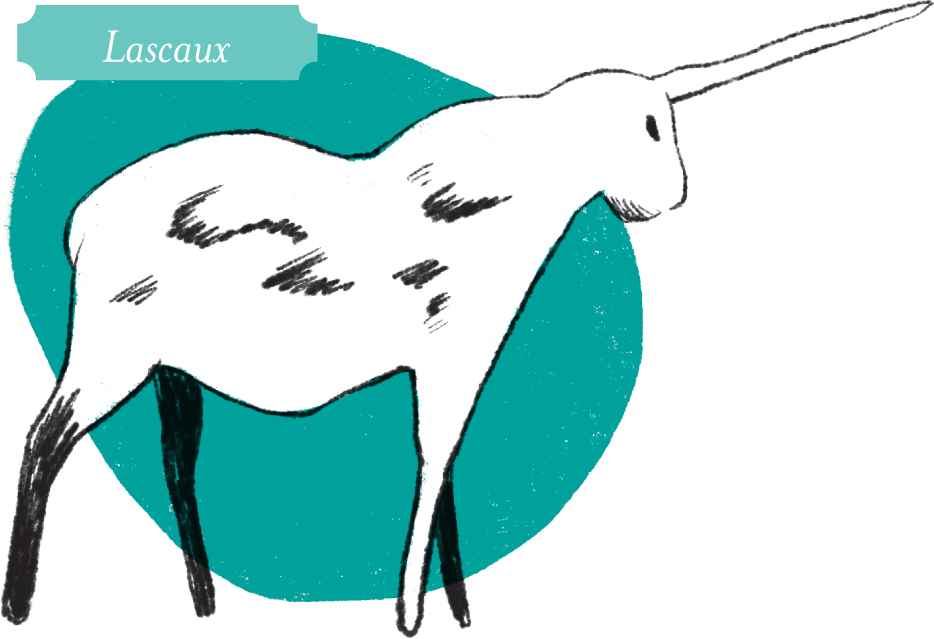

In Dordogne, France, some of the worlds oldest cave paintings are preserved at Lascaux. Giant animals, painted about , years ago in bold lines of black, brown, and red, sprawl across the ceilings and walls of a system of underground caverns. Among the oxen, stags, deer, horses, and big cats, there is one mysterious creature archaeologists nicknamed the unicorn, because of the long, straight horn that juts from its forehead.

Many people insist that Lascauxs unicorn actually has two horns, but unicorn lovers are free to draw their own conclusions about what the ancient painters intended. Even so, few people would recognize the creature in the caves as a relative of the animals we see in art today. Lumpy and spotted, with a short tail and a blunt nose, the Lascaux unicorn is a far cry from the graceful white horses that unicorns would later become.

When most people think of unicorns, they imagine a creature from a much later time: the Middle Ages. With flowing manes and spiral horns, they belong to the world of knights in armor and maidens in flowing gowns. And they come from a very specific place, too. The shining white horse-like unicorn that we know and love was first described in Europe. But unicorns throughout history and around the world have taken on many different forms.

And, truth be told, a lot of them looked more like the strange creature at Lascaux than the beautiful equines in our imaginations.

The history of the unicorn in Europe began around the fourth century BCE, in Greece. At the height of ancient Greek civilization, many scholars were interested in understanding and describing the natural world. Almost two thousand years before the printing press would be invented, they collected stories that described cultures and wildlife from other parts of the world in handwritten scrolls that could be copied by scribes and shared with other scholars.

Since it would also be thousands of years before cars, trains, or airplanes were invented, few scholars actually saw the creatures they were describing. Instead, they collected stories from travelers who spread out from Greece, mostly to trade with other cultures. This kind of information gathering allowed the ancient Greek philosophers to gain knowledge on subjects far beyond what they could have gathered on their own. But it also left room for a lot of mistakes. Stories were passed from one traveler to another, and like anyone playing a long game of telephone, scholars were likely to misinterpret at least some of the information.

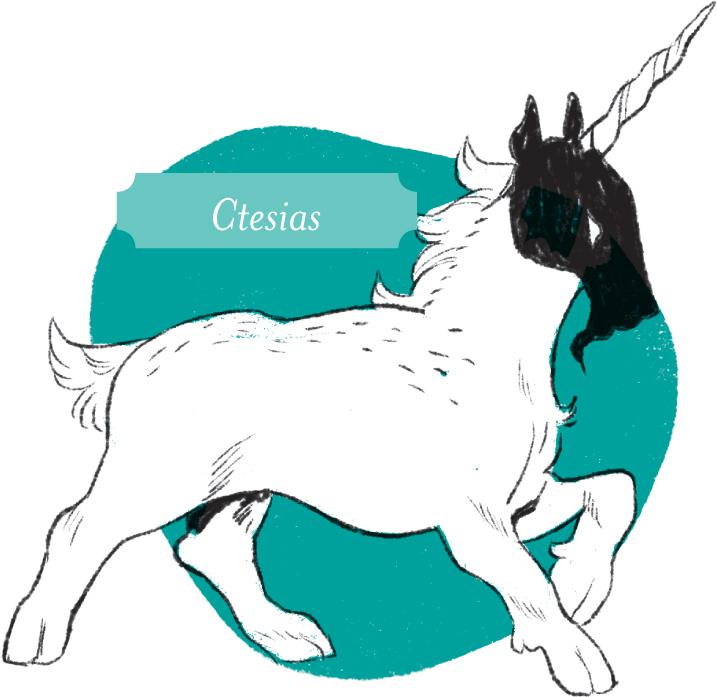

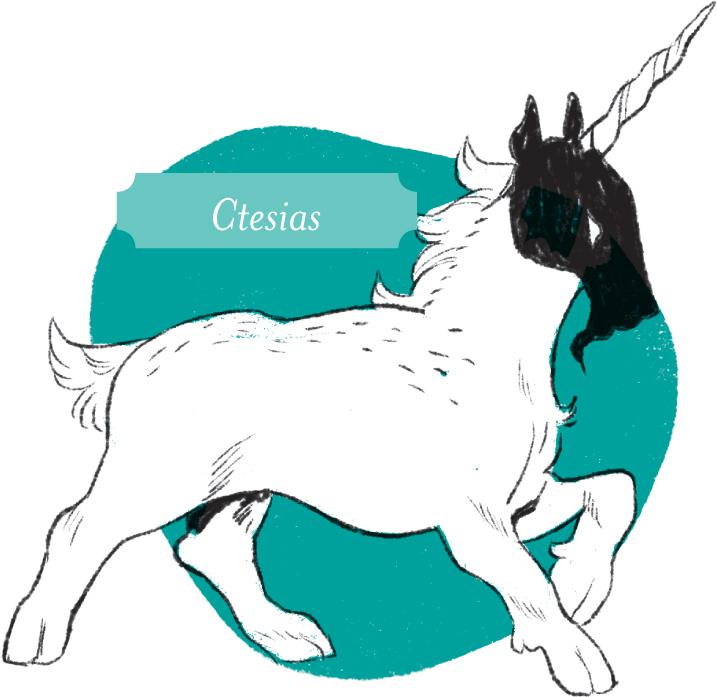

One of those Greek scholars was a physician named Ctesias, who wrote about Persia and India. Ctesias was appointed as physician to the court of a Persian king (in what is now Iran), and lived there for seventeen years learning about Persian history and culture. When he returned to Greece in the year BCE, he began writing two enormous scholarly works. One of them, called Indica, described what he had learned about India. (Although he called it India, Ctesias was probably referring to the region around Tibet.) While Ctesias had never made it to the land he was describing, he met travelers who had. Based on their stories, Ctesias wrote what was probably the first European story of a unicorn.

Ctesiass unicorn shared some qualities with the unicorn of today: It was about the size of a horse and had a straight horn, about one and a half feet long, jutting from the middle of its forehead. But Ctesiass unicorn was a wild donkey, and while its body was white, its head was deep red and its eyes dark blue. Weirder still, its horn was three different colors: white at the base, black in the middle, and vivid red at the tip. It was an impressive beast. Ctesias said that the unicorn was exceedingly swift and powerful and no other animal could catch it. Strange though Ctesiass creature might seem to us today, it was the first many Europeans heard of the unicorn, and many, many later tales would be based on his description.