Copyright Michele H. Bogart 2018

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

INTRODUCTION

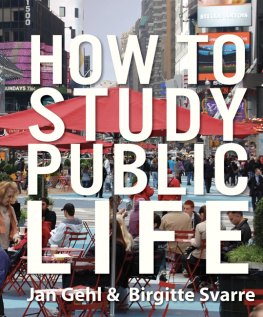

B old, flashy, whimsical, colorful, interactive, occasionally cerebral or didactic, and often tongue in cheekpublic sculpture is a hot commodity in the contemporary city. This trend is especially widespread in New York City; public sculpture plays a conspicuous role there as heritage, decor, entertainment, tourist attraction, and community icon. It contributes to a sense of order and helps drive the citys economic engines. (Paradoxically, it also serves to distract from the disorientating effects of gentrification, generated by such development.) Public art also showcases the municipalitys support for its creative classes: an administrations engagement with the arts and its enlightened cultural policies. Recent New York City mayors have provided strong support, facilitating ambitious projects such as The Gates (Christo and Jeanne-Claude, on view February 1228, 2005), The New York City Waterfalls (Olafur Eliasson, on view June 26October 13, 2008), Jeff Koonss 2014 Split Rocker (on view June 25September 18, 2014), and Kara Walkers A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby (on view May 10July 6, 2014). City agencies and public authorities have specific programs (such as the Percent for Art program of the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and the Arts and Design program of the Metropolitan Transit Authority) that commission permanent public art. The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation collaborates with almost all of the other

Indeed, public sculpture is now integral to municipal New York Citys vibrancy and identity. Crowds milling at Doris Freedman Plaza (Fifth Avenue at 60th Street) on a sunny day, or posing for selfies alongside of Kristen Visbals pop-up bronze Fearless Girl in lower Manhattan (February 2017February 2018) are representative of the excitement or controversy that public art can provoke. Popular among ordinary Americans and widely covered in the press, temporary works such as these, along with permanent sculptures such as Alamo or Frederick Douglass, highlight how art in the public realm has become a significant cultural stimulus.

SIXTY YEARS AGO, the situation was very different. The postwar New York cityscape was in the doldrums. Following developments of the Depression and wartime, when neither private sector nor city government commissioned much in the way of architectural sculpture or freestanding monuments, civic sculpture was on the wane. Architects, who in previous decades had included sculptural adornments on their buildings, were generally moving in a different direction. The earlier generation of academic sculptors who received monument commissions was aging or dying off. There was little propensity to find alternatives. It is thus noteworthy that circumstances changed so dramatically: that powerful officials came to regard public sculpture as central to the image of an energizing yet orderly New York and enthusiastically took on the mantle of public art benefactor. What happened?

This book, a case study of the politics of public art patronage in New York City, examines how these changes in attitude and artisticurban planning occurred. It looks at how and why municipal government became involved in showcasing sculpture during the post-hero statue era, beginning around 1965. Although it was not the first to develop comprehensive public sculpture programs, New York Citys activities were among the most expansive. The enterprise was especially notable because public art was hardly a matter with which New York City was obligated to engage as a quality of life or public safety matter, but nonetheless did so. The city not only permitted public artworks to be installed temporarily on municipal land (mostly parks), but gradually became an active sponsor. By 1982, in fact, the city became committed to patronage as a matter of cultural policy, through Percent for Art legislation.

New York City in the 1950s was a city emerging from wartime stagnation, economic decline, and an absence of mayoral authority. Municipal and business leaders focused on bolstering employment, rebuilding the Lower Manhattan business district, increasing housing stock, managing traffic, and accommodating the automobile.

In the mid-1960s, however, attitudes and approaches underwent a shift. The generation of bureaucrats following Moses and his Parks Commissioner successor Newbold Morris took the challenge of a changing New York City as an opportunity to embrace art, especiallypublic art, as a force that could enhance the city. Sculpture in Gotham examines these developments beginning in the mid-1950s, when Mosess structured vision of the city still held sway, along with his conservative tastes. It ends in the present day, the late 2010s, when the major organizational structures, programs, and procedures for public art production have been put to the test.

The new institutions, which included the Public Art Council, Public Art Fund, Creative Time, and the Percent for Art program (which spawned others, such as Metropolitan Transit Authoritys (MTAs) Arts for Transit and the Department of Transportation Urban Art Program), were inspired by sociopolitical and cultural developments of the mid-1960s, and were made possible by some of the same people. This cohort, led most notably by Doris Freedman, was active as part of the liberal administration of Mayor John V. Lindsay. The Lindsay people were contending with new challenges: poverty, a stagnant real estate market in the citys commercial districts, racial and ethnic tensions in inner-city neighborhoods, left-wing anti-Vietnam War protests, and the ascendance of youth culture with access to mind-altering drugs. Moses, focusing on order, painted the city in broad, summary strokes in the 1950s and provided instruments for structured play. Lindsay officials such as Thomas Hoving, August Heckscher, and Doris Freedman had a more indulgent approach. Buoyed by Kennedy liberalism, and more detail- and people-oriented, they encouraged the idea of an open city, and promoted streets and parks as egalitarian spaces for self-actualization, free play, and community enrichment. Public sculpture became one of the instruments for revitalizing the city.

Freedman was a key spokesman. Committed to the idea that contemporary art in the public realmModernist public sculpture in particularhad life-enhancing, liberating potential for the people of the city, Freedman persuaded Lindsay officials to embrace it as part of a plan with several agendas. A key concern was toheighten New Yorkers awareness and appreciation of their surroundings to promote community pride and social empowerment: to help keep the peace at a politically volatile moment. Insofar as artists were key to this effort, a secondary concern was to help them professionally, as well as to encourage individual creativity. An initial endeavor started with the (ponderously titled) Washington Heights-Inwood-Marble Hill Community Environmental Sculpture Program. Freedman, along with women such as Anita Contini, Margot Wellington, Suzanne Randolph, and Jenny Dixon, then formed and facilitated new private-public initiatives. The public sculpture enterprise ultimately extended to the entire city, through the establishment of Percent for Art.