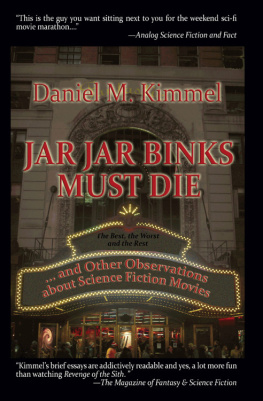

Jar Jar Binks Must Die

and other Observations about Science Fiction Movies

by

Daniel M. Kimmel

Copyright

2011 by Daniel M. Kimmel

Smashwords Edition

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission except for brief quotations for review purposes only.

Editor: Ian Randal Strock

Fantastic Books

1380 East 17 Street, Suite 2233

Brooklyn, New York 11230

www.FantasticBooks.biz

Print ISBN 10: 1-61720-350-5

Print ISBN 13: 978-1-61720-350-3

First Edition, Version 1.1

Dedication

Dedicated with affection and gratitude to four friends

who were there when I needed them most:

Betty Smithline

Dr. Davin Wolok

Michael Devney

and, always, Sido Surkis

Table of Contents

IntroductionScience Fiction: the Forbidden Genre

Acknowledgments

Part I. Mandatory Viewing

Days of Futures Passed

Future Tense

Science Fiction or Not?

Sleep No More

Real Aliens Dont Ask Directions

Keeping Watch

Dont Call Me Shirley

Red Alert

2001: A Space Odyssey in 2001

Nerds in Love

We Come in Pieces: The Alien as Metaphor

But Somebodys Got to Do It

Blue Genes

2009: A Miracle Year?

PART II. Camera Obscura

SF, My Parents, and Me

Destination Moon in the 21st Century

Our Batman

Atomic Ants

The Bare Necessities

Being and Nothingness: The Movie

My Bloody Valentine

Love in the Time of Paradox

Ironic, Isnt It?

The Ultimate Book Movie

The Mystery of The Woman in the Moon

1953

Retro Robo

The Cranky Persons Guide to the 2009 Best Dramatic Presentation, Long Form Hugo Nominees

The Future is Now

Were Scientists, Trust Us

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Future

Not Coming to a Theater Near You

Watching Me, Watching You

The Time Travelers Movie

Part III. Bargain Bin

Remake Love, Not War

Gilligans Island Earth

Guilty Pleasures

Mars Concedes!

E.T. Go Home

Jar Jar Binks Must Die

Post ScriptThe Modern Classics: A First Draft

Publication History

Introduction: Science Fiction: The Forbidden Genre

If theres a common theme to the essays in this book, which were written over a ten year period, it is this: science fiction films are worth discussing. Better yet, science fiction films are as worthy as any other kind of film for serious discussion. One would think that would not only be non-controversial but so transparently obvious that it wasnt even worth mentioning. Alas, such is not the case.

Imagine a world where an Oliver Stone could say in an interview, Platoon isnt a Vietnam War movie. Its really about people. Or perhaps Clint Eastwood explaining that Unforgiven isnt a western at all, but simply uses the trappings of the genre to explore relationships. Or perhaps Meryl Streep insisting that Its Complicated isnt like those other romantic comedies and, in fact, isnt a romantic comedy at allits about a womans issues in remodeling her kitchen. You probably cant imagine such things. These excuses are so transparently absurd and so in opposition to the films themselves that if such explanations had been seriously offered you would think these folks were deranged.

Yet writers, directors, and actors who come from outside the genre to create works of science fiction often deny that it is, in fact, science fiction that they have created. Theyll even insist that their books and films arent actually science fiction at all. Unlike what you might expect from this apparently unspeakable and unworthy genre, their works are about people. The most notoriousand laughableexample of this was when Margaret Atwood, author of such novels as The Handmaids Tale, argued that her dystopian and speculative books couldnt possibly be science fiction. SF, as she defined it, was about talking squids in space. In these pages youll find numerous examples of critics, film historians and others insisting that movies like Frankenstein, The Time Travelers Wife, and even Metropolis arent really science fiction. One could just laugh off these people as ignorant or prejudiced, for many of them are, but its such a widely held belief that you come to realize that some of these filmmakers and stars and authors are doing this in self-defense. In effect what theyre saying is, Please dont put me and my work in the science fiction ghetto. We want to be taken seriously. Even writers friendly to the genre and who obviously liked writing in it, such as the late Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., knew that one could be treated as a serious author or as a science fiction writer, but not both.

At the risk of setting up the proverbial straw men, lets consider some of the arguments as to why SF movies are deemed unworthy of serious critical consideration:

* Theyre childish. Most of it is geared to the mentality of 12 year old boys.

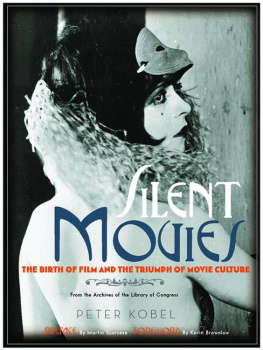

While, as a well known quote attributed to SF fan Peter Graham has it, the golden age of science fiction is 12, it is nonsensical to argue that all or even most science fiction is intended for non-adults. Part of the problem is that while there are early examples of science fiction in both literature and film, it wasnt firmly established as a film genre until the 1950s. So while we can point with pride to Georges Mlis and his A Voyage to the Moon and Fritz Langs Metropolis as two landmark films that bookend the silent era and William Cameron Menzies Things to Come as a fascinating film that had the participation of H.G. Wells himself, Hollywoods pre-World War II overtly SF offerings were the musical curio Just Imagine and the Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers movie serials. Prior to Destination Moon in 1950, which started Hollywoods first SF boom, American science fiction films were largely for kids. When something was serious and unambiguously SF, such as Frankenstein or The Invisible Man, it got classified as part of Universals monster movie cycle. Science fiction would get the blame, but never the credit.

* Science fiction writing isnt literature. It started out in those lurid pulp magazines.

Even putting aside author Brian Aldisss claim for Mary Shelleys Frankenstein as the first true SF novel, only two authors of science fiction were admitted to the modern literary canon before the guardians of cultural standards barred the door: Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. Two later entries, George Orwells 1984 and Aldous Huxleys Brave New World, were obviously important works which could not be denied and thus could not bear the taint of the science fiction label, and so would be treated as satires or dark warnings about the present day world. In contrast, nothing written for cheap magazines printed on even cheaper paper would be considered worthy of attention. Well, unless it was written by Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler or any of the other hard-boiled authors who laid the groundwork for not only literary crime fiction (modernizing a genre arguably invented by Edgar Allan Poe), but also providing the stories for the complex cinematic genre of film noir. A dividing line here was that most SF wasnt marketed in book form until the 1950s. James M. Cains Double Indemnity had come out in hardcover long before Billy Wilder did his great film adaptation of it. By contrast, an outstanding film like The Day the Earth Stood Still was based on a short story (Farewell to the Master by Harry Bates) that had appeared in the pulp magazine Astounding a decade before. It might or might not have been known by fans, but virtually no one else would have been familiar with it. Without a literary underpinning as a genre, it was hard to get SF films thought of as part of a tradition.

Next page