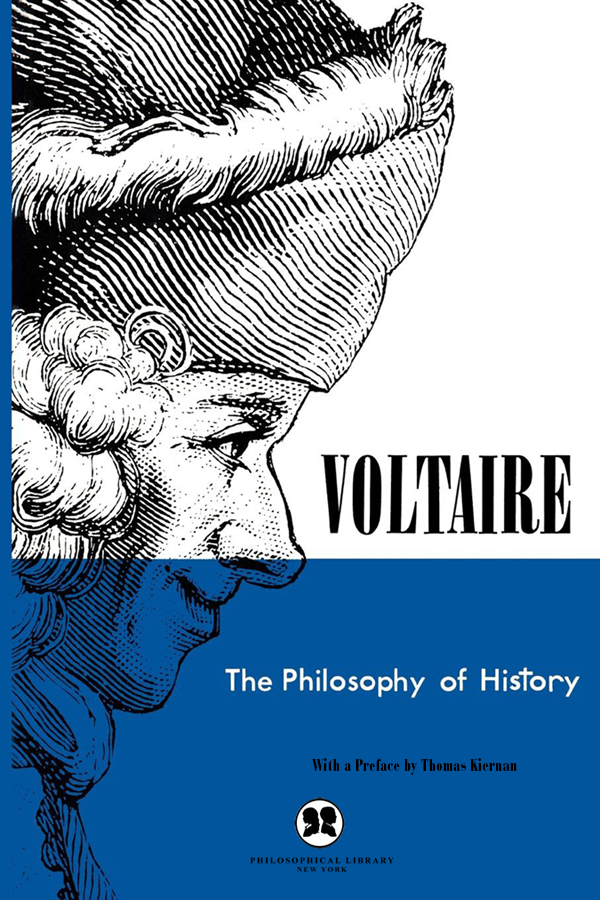

I

INTRODUCTION

YOU WISH that ancient history had been written by philosophers, because you are desirous of reading it as a philosopher. You seek for nothing but useful truths, and you say you have scarce found anything but useless errors. Let us endeavor mutually to enlighten one another; let us endeavor to dig some precious monuments from under the ruins of ages.

We will begin by examining, whether the globe, which we inhabit, was formerly the same as it is at present.

Perhaps our world has undergone as many changes, as its states have revolutions. It seems incontestable that the ocean formerly extended itself over immense tracts of land, now covered with great cities, and producing plenteous crops. You know that those deep shell-beds, which are found in Touraine and elsewhere, could have been gradually deposited only by the flowing of the tide, in a long succession of ages. Touraine, Britanny and Normandy, with their contiguous lands, were for a much longer time part of the ocean, than they have been provinces of France and Gaul.

Can the floating sands of the northern parts of Africa, and the banks of Syria in the vicinity of Egypt, be anything else but sands of the sea, remaining in heaps upon the gradual ebbing of the tide? Herodotus, who does not always lie, doubtless relates a very great truth, when he says, that according to the relations given by the Egyptian priests, the Delta was not always land. May we not say the same of the sandy countries towards the Baltic sea? Do not the Cyclades manifestly indicate, by all the flats that surround them, by the vegetations, which are easily perceptible under the water that washes them, that they made part of the continent?

The Straights of Sicily, that ancient gulf of Charybdis and Scylla, still dangerous for small barks, do they not seem to tell us that Sicily was formerly joined to Apuleia, as the ancients always thought? Mount Vesuvius and mount Etna have the same foundations under the sea, which separates them. Vesuvius did not begin to be a dangerous volcano, till Etna ceased to be so; one of their mouths casts forth flames, when the other is quiet. A violent earthquake swallowed up that part of this mountain, which united Naples to Sicily.

All Europe knows that the sea overflowed one-half of Friesland. About forty years ago, I saw the church steeples of eighteen villages, near Mardyke, which still appeared above the inundation, but have since yielded to the force of the waves. It is reasonable to think that the sea in time quits its ancient banks. Observe Aiguemonte, Frejus, and Ravenna, which were all sea-ports, but are no longer such Observe Damietta, where we landed in the time of the Crusades, and which is now actually ten miles distant from the shore, in the midst of land. The sea is daily retiring from Rosetta: nature every where testifies those revolutions; and if stars have been lost in the immensity of space, if the seventh Pleiade has long since disappeared, if others have vanished from sight into the milky way, should we be surprised that this little globe of ours undergoes perpetual changes?

I dare not, however, aver that the sea has formed or even washed all the mountains of the earth. The shells which have been found near mountains, may have there been left by some small testacious fish, the inhabitants of lakes; and these lakes, which have been moved by earthquakes, may have formed other lakes of inferior note. Ammons horns, the starry stones, the lenticulars, the judaics, and glossopetrae appeared to me as terrestrial fossils. I did not dare think that these glossopetrae could be the tongues of sea dogs; and I am of opinion with him who said one might as easily believe that some thousands of women came and deposited their conchae veneris upon a shore, as to think that thousands of sea dogs came there to leave their tongues.

Let us take care not to mingle the dubious with the certain, the false with the true; we have proofs enough of the great revolutions of the globe, without going in search of fresh ones.

The greatest of these revolutions would be the loss of the Atlantic land, if it were true that this part of the world ever existed. It is probable that this land consisted of nothing else than the island of Madeira, discovered perhaps by the Phenicians, the most enterprising navigators of antiquity, forgotten afterwards, and at length rediscovered, in the beginning of the fifteenth century of our vulgar era.

In short, it evidently appears by the slopes of all the lands which are washed by the ocean, by those gulfs which the eruptions of the sea have formed, by those archipelagoes that are scattered in the midst of the waters, that the two hemispheres have lost upwards of two thousand leagues of land on one side, which they have regained on the other.

II

OF THE DIFFERENT RACES OF MEN

WHAT IS the most interesting to us, is the sensible difference in the species of men, who inhabit the four known quarters of the world.

None but the blind can doubt that the whites, the negroes, the Albinoes, the Hottentots, the Laplanders, the Chinese, the Americans, are races entirely different.

No curious traveller ever passed through Leyden, without seeing part of the reticulum mucosum of a negro dissected by the celebrated Ruish. The remainder of this membrane is in the cabinet of curiosities at Petersburg. This membrane is black, and communicates to negroes that inherent blackness, which they do not lose, but in such disorders as may destroy this texture, and allow the grease to issue from its cells, and form white spots under the skin.

Their round eyes, squat noses, and invariable thick lips, the different configuration of their ears, their woolly heads, and the measure of their intellects, make a prodigious difference between them and other species of men; and what demonstrates, that they are not indebted for this difference to their climates, is that negro men and women, being transported into the coldest countries, constantly produce animals of their own species; and that mulattoes are only a bastard race of black men and white women, or white men and black women, as asses, specifically different from horses, produce mules by copulating with mares.

The Albinoes are, indeed, a very small and scarce nation; they inhabit the center of Africa. Their weakness does not allow them to make excursions far from the caverns which they inhabit; the negroes, nevertheless, catch some of them at times, and these we purchase of them as curiosities. I have seen two of them, a thousand other Europeans have seen some. To say that they are dwarf negroes, whose skin has been blanched by a kind of leprosy, is like saying that the blacks themselves are whites blackened by the leprosy. An Albino no more resembles a Guinea negro, than he does an Englishman or a Spaniard. Their whiteness is not like ours, it does not appear like flesh, it has no mixture of white and brown; it is the color of linen, or rather of bleached wax; their hair and eye-brows are like the finest and softest silk; their eyes have no sort of similitude with those of other men, but they come very near partridges eyes. Their shape resembles that of the Laplanders, but their head that of no other nation whatever; as their hair, their eyes, their ears, are all different, and they have nothing that seems to belong to man but the stature of their bodies, with the faculty of speaking and thinking, but in a degree very different from ours.

The apron, which nature has given to the Caffres, and whose flabby and lank skin falls from their navel half way down their thighs; the black breasts of the Samoiedes women, the beard of the males of our continent, and the beardless chins of the Americans, are such striking distinctions, that it is scarce possible to imagine that they are not each of them of different races.