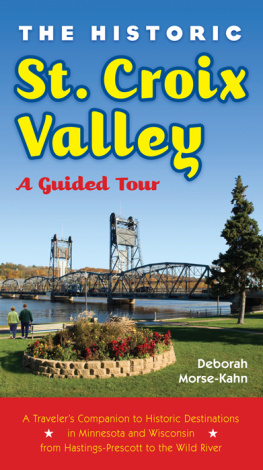

THE HISTORIC

ST. CROIX

VALLEY

Deborah Morse-Kahn

Minnesota Historical

Minnesota Historical

Society Press

2010 by the Minnesota Historical Society. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, write to the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 55102-1906.

www.mhspress.org

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the

Association of American University Presses.

Manufactured in U.S.A.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 21

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum

requirements of the American National Standard for

Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library

Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Credits

Front cover: iStockphoto.com/Lawrence Sawyer

Back cover: Judd Street Looking North 1906, Carl Arthur

Ecklund, MHS collections

Interior: images pages 162 and 198, Wisconsin Historical

Society. All others, MHS collections.

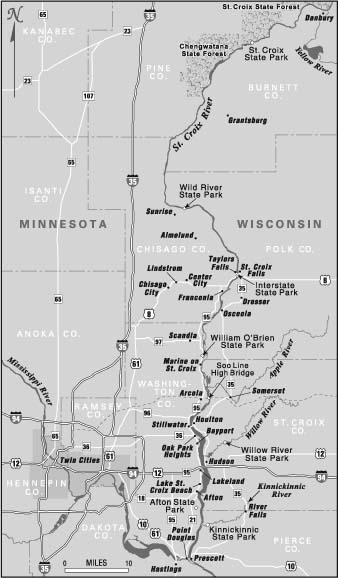

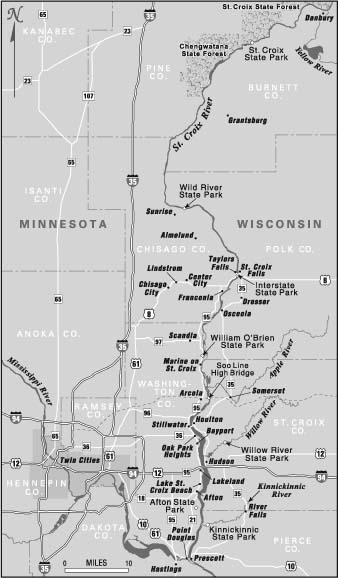

Maps: CartoGraphics Inc.

Design: Percolator

International Standard Book Number

ISBN: 978-0-87351-774-4 (paper)

ISBN: 978-0-87351-799-7 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Morse-Kahn, Deborah, 1952

The historic St. Croix valley: a guided tour/

Deborah Morse-Kahn.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87351-774-4 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Saint Croix River Valley Region (Wis. and Minn.)Tours.

2. Historic sitesSaint Croix River Valley Region (Wis. and Minn.)Guidebooks.

3. Historic buildingsSaint Croix River Valley Region (Wis. and Minn.)Guidebooks.

4. Saint Croix River Valley Region (Wis. and Minn.)History, Local.

I. Title. II. Title: Historic Saint Croix valley.

F612.S2M67 2010

977.659dc22

2010013527

For James Taylor Dunn (1912-2002)

Historian, Librarian, Advocate, Educator, Author

Protector and Biographer of the St. Croix River

PREFACE

This book was written as historic structures were being razed and stories of entire cities were being swept away in the path of modern improvements. As always, such documentation and description has come just in time, if not perhaps a moment too late, since it takes real loss for us to rally in the effort to preserve markers of our collective past. And as always, such documentation and description can help the generations that both see their past as a thing of great worth and want to know more.

The St. Croix Valleys history has so many facets. In the midst of spectacular geography and geology, First Nation peoples, European traders, and immigrants who founded villages made use of the river and its natural gifts to survive. Industry and commerce became the driving force of life on the St. Croix from the 1840s forward, leaving for us physical reminders in stone and brick for shelter, for civic endeavor, and for industry. Many of these physical markers have been lost over 150 years, but marvelous examples still stand, at home in a river valley landscape that remains remarkably unchanged since the days of territorial designation.

And finally, the river itself is in parts wild and untamed and in others controlled and corralled. Environmental management of the St. Croix River has been a one-hundred-year undertaking and continues with passion today.

May this book further encourage the preservation of the entire St. Croix Valley, for us, for those who have passed and gone, and for our children and their children.

Overview: The St. Croix Valley

THE ST. CROIX

STORY

The St. Croix River is a peaceful passage between modern cities that joins the great Mississippi and mingles with its waters. It is also, at one point, a placid and beautiful lake, a small sea from side to side, along which for thousands of years people have found shelter, sustenance, and a sustainable way of life. The river has been controlleddammed, managed, and modifiedfor modern business needs and less treacherous passage, yet it also remains a wild river, flowing freely, rushing south, and joining hands with its tributaries large and small. A magnificent ecosystem has evolved that, today, we honor, preserve, conserve, and monitor with great care.

For thousands of years, though, the St. Croixfrom its natural glacial dam in the northwest of present-day Wisconsin to its confluence with a much larger sibling, the Mississippi Riverwas a source of food, a source of transport, and a source of seasonal sustenance in furs, bark, rushes, blueberries, and drinking water for Native Americans.

Eventually, the Native Americans in this area made contact with European explorers, then trappers and traders, and then entire trading companies. The lands of the new territories were explored, described, and surveyed. Fur traders, speaking English, French, and Algonquian languages, who had partnered for commerce stayed for a lifetime, often marrying women from their Native American trading villages.

The American Fur Company promoted the establishment of trading posts; the federal government built forts to keep order in the raw new lands. The French had made their own mark on the land and on the water and on its peoples, and the voyageurs, les coureurs de bois (carriers of the woods), gave this great river its name.

Dalles of the St. Croix, Elijah Evan Edwards, 1880

Treaties were written with tribal nations, offering federal support and guaranteed trade, in exchange for lands burgeoning with white pine and minerals. The Treaty of 1837 ceded the pineries to the American government. Again and again, the Ojibwe, Dakota, Ho-Chunk, Fox, Sac, and Mesqwaki nations were herded into ever tighter blocks of land and were forced into dependence on the European benefactors through annuities and, increasingly, alcohol.

Lands belonging to these tribes were taken away, sometimes honorably, frequently dishonorably, and using these lands and what grew theretimberthe Wisconsin and Minnesota territories helped to build an empire, establish new states in the Union, and make a great many people extraordinarily wealthy. The valley and its industry provided a haven for immigrants for whom life at homethe impoverished farmlands of Sweden, the religious oppression of France, the barren potato fields of Irelandwas no longer sustainable.

Lumber was in such plenty that men moved inland from the river and took as much as they could, long before the federal government had given permission to cut the old-growth forests of white pine, oak, maple, and walnut. By the 1850s, lumbering was the occupation of area entrepreneurs, who founded logging companies and built mills to saw what the company employees had sent downriver. The camps in the pineries in winter were brutal and basic, but it was honest labor, gave a man good, hard work, and also provided that uniquely American eventthe mingling of many ethnicities and races for a common cause. In their time the Swedes and the Italians worked among the Ojibwe and the English and the Irish and the Germans. And all who could farm did so, and those who could not planted vegetable gardens.

Minnesota Historical

Minnesota Historical