Contents

Guide

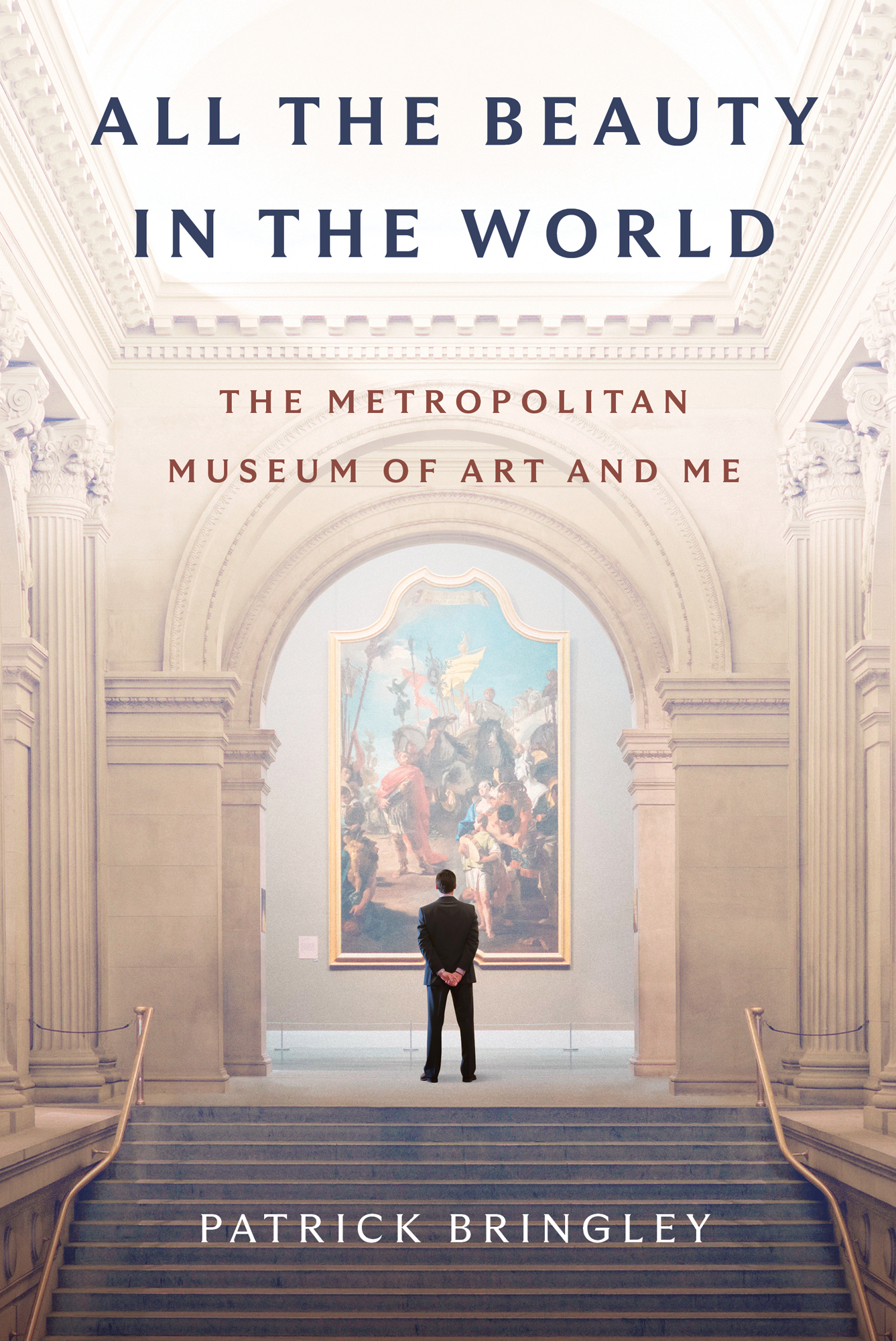

All the Beauty in the World

The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me

Patrick Bringley

For Tom

AUTHORS NOTE

Information about every artwork referenced in the text can be found beginning on , along with resources for locating objects in the galleries and viewing high-resolution images at home.

This book is composed of real events from my ten years as a museum guard. In an effort to write scenes that demonstrate the range of my experience, Ive sometimes put incidents together that happened on different days. The names of museum personnel have been changed.

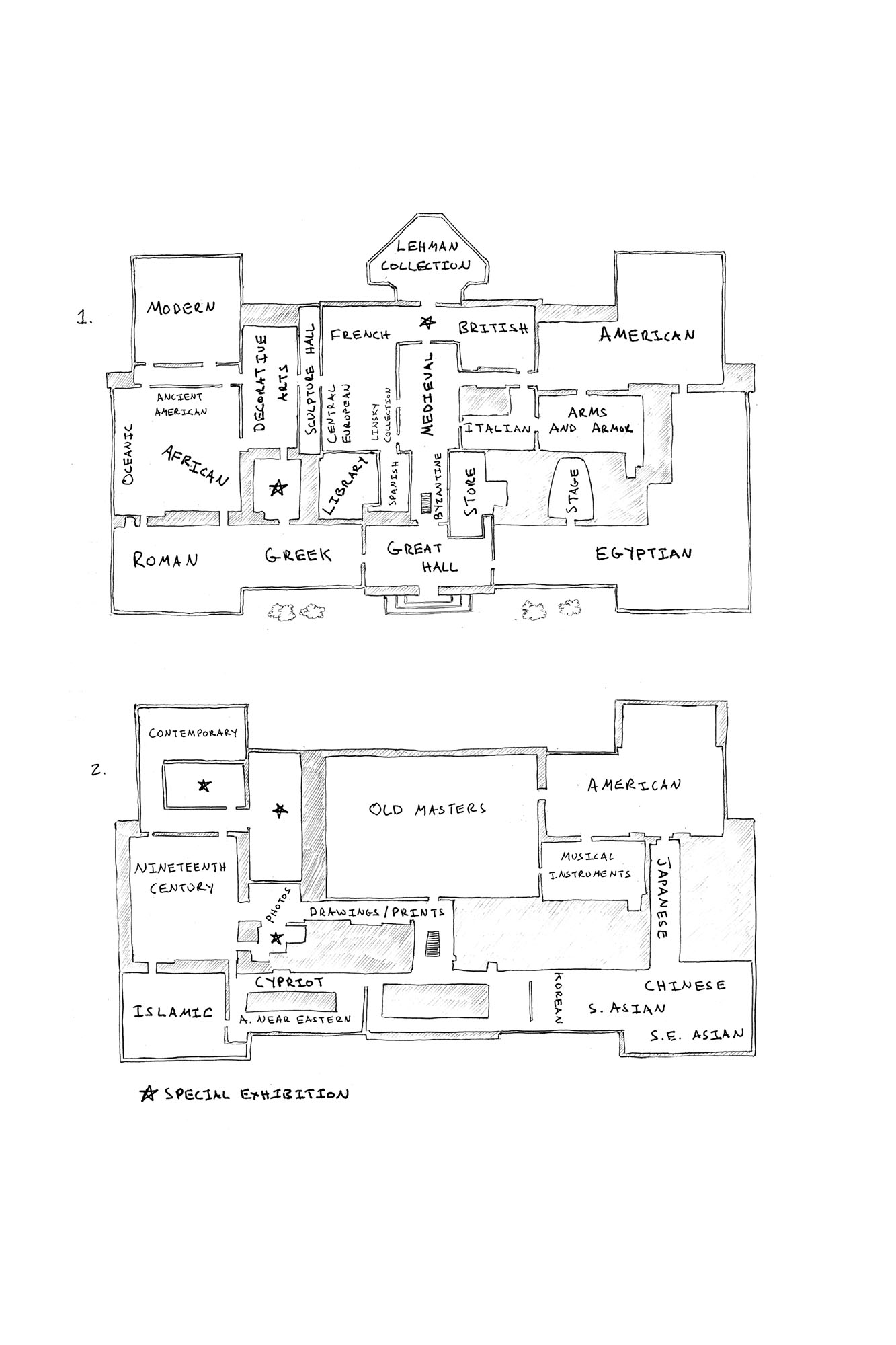

I. THE GRAND STAIRCASE

I n the basement of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, below the Arms and Armor wing and outside the guards Dispatch Office, there are stacks of empty art crates. The crates come in all shapes and sizes; some are big and boxy, others wide and depthless like paintings, but they are uniformly imposing, heavily constructed of pale raw lumber, fit to ship rare treasures or exotic beasts. On the morning of my first day in uniform I stand beside these sturdy, romantic things, wondering what my own role in the museum will feel like. At the moment I am too absorbed by my surroundings to feel like much of anything.

A woman arrives to meet me, a guard I am assigned to shadow, called Aada. Tall and straw haired, abrupt in her movements, she looks and acts like an enchanted broom. She greets me with an unfamiliar accent (Finnish?), beats dandruff off the shoulders of my dark blue suit, frowns at its poor fit, and whisks me away down a bare concrete corridor where signs warn: Yield to Art in Transit. A chalice on a dolly glides by. We climb a scuffed staircase to the second floor, passing a motorized scissor lift (for hanging paintings and changing light bulbs, Im told). Tucked beside one of its wheels is a folded Daily News, a paper coffee cup, and a dog-eared copy of Hermann Hesses Siddhartha. Filth, Aada spits. Keep personal items in your locker. She pushes through the crash bar of a nondescript metal door and the colors switch on Wizard of Ozstyle as we face El Grecos phantasmagoric landscape, the View of Toledo. No time to gape. At Aadas pace, the paintings fly by like the pages of a flip-book, centuries rolling backward and forward, subject matter toggling between the sacred and profane, Spain becoming France becoming Holland becoming Italy. In front of Raphaels Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints, almost eight feet tall, we halt.

This is our first post, the C post, Aada announces. Until ten oclock we will stand here. Then we will stand there. At eleven we will stand on our A post down there. We will wander a bit, we will pace, but this, my friend, is where we are. Then we will get coffee. I suppose that this is your home section, the old master paintings? I tell her yes, I believe so. Then you are lucky, she continues. You will be posted in other sections too eventuallyone day ancient Egypt, the next day Jackson Pollockbut Dispatch will post you here your first few months and after that, oh, sixty percent of your days. When you are hereshe stamps twicewood floors, easy on the feet. You might not believe it, my friend, but believe it. A twelve-hour day on wood is like an eight-hour day on marble. An eight-hour day on wood is like nothing. Pfft, your feet will barely hurt.

We appear to be in the High Renaissance galleries. On every wall, imposing paintings hang from skinny copper wires. The room, too, is imposing, perhaps forty feet by twenty, with egress through double-wide doorways leading in three directions. The floor is as mellow as Aada had promised, and the ceiling is high, with skylights aided by lamps pointing down at various strategic angles. There is a single bench near the center of the room, upon which lies a discarded Chinese-language map. Past the bench, a pair of wires dangle loosely toward a conspicuously empty spot on the wall.

Aada addresses it: You see the signed paper slip, she says, motioning toward the sole evidence this isnt a shocking crime scene. Mr. Francesco Granacci was hanging here, but the conservator has taken him in for a cleaning. He might also have been out on loan, under examination in the curators office, or having his picture taken in the photography studio. Who knows? But there will be a slip and that you will notice.

We pace along a shin-high bungee cable, which keeps us a yard or so from the paintings, and enter the next gallery under our watch. Here, Botticelli appears to be the famous name; and after that there is a third, smaller gallery, dominated by more Florentines. This is our domain until 10 a.m., when we will shift to the three galleries beyond. Protect life and propertyin that order, Aada continues, beginning to lecture with uniform staccato emphasis. Its a straightforward job, young man, but we also must not be idiots. We keep our eyes peeled. We look around. Like scarecrows, we prevent nuisance. When there are minor incidents, we deal with them. When there are major incidents, we alert the Command Center and follow the protocols you learned in your classroom training. We are not cops except for when idiots ask us to be cops, and thankfully it isnt often. And as its the first thing in the morning, there are a couple of things we must do.

Returning to the Raphael gallery, Aada gets on her tiptoes to stick a key in a lock and open a glass door on to a public stairwell. This done, she casually steps over a bungee cablea startling transgression to witnessand drops to her haunches beneath a heavy golden frame. The lights, she says, indicating switches in the baseboard. Usually the late watchthats the midnight shiftwill have turned them on, but in case they havent. She depresses a half dozen switches at once, and we are standing in a long dark tunnel, Renaissance paintings turned into silvery muddles on the walls. She flips the switches up and the lights kick on a gallery at a time with surprisingly loud ka-chunks.

The public starts trickling in about 9:35. Our first visitor is an art student judging by the portfolio under her arm, and she actually gasps to find herself all alone. (Perhaps rightly, she doesnt count Aada and me.) A French family follows in matching New York Mets caps (which they likely believe to be Yankees caps, the more typical tourist choice), and Aadas eyes narrow. For the most part, our visitors are lovely, she admits, but these pictures are very old and fragile, and people can be very stupid. Yesterday I was working in the American Wing, and all day long people wanted to seat their children on the three bronze bears! Can you imagine? With the old masters, its much betternot so quiet as Asian Art, of course, but a piece of cake compared to the nineteenth century. Of course, everywhere we work we must look out for unthinking individuals. You see? Right there. Across the way, the French father is reaching over the bungee line, pointing out some Raphaelesque detail to his daughter. Monsieur! Aada calls out, somewhat louder than she needs to. Sil vous plait! Not so close!

After a little while, an older man saunters into the gallery wearing a familiar suit of clothes. Oh good, its Mr. Ali, an excellent teammate! Aada says of the guard.

Ah, Aada, the very best! he replies, catching and adopting her cadence. Mr. Ali introduces himself as the relief on our team (team one, Section B) who is pushing us along to our B post.