The Complete Canadian Book Editor

Leslie Vermeer

Copyright 2016 Leslie Vermeer

16 17 18 19 20 5 4 3 2 1

Printed and manufactured in Canada

Thank you for buying this book and for not copying, scanning, or distributing any part of it without permission. By respecting the spirit as well as the letter of copyright, you support authors and publishers, allowing them to continue to create and distribute the books you value.

Excerpts from this publication may be reproduced under licence from Access Copyright, or with the express written permission of Brush Education Inc., or under licence from a collective management organization in your territory. All rights are otherwise reserved, and no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, digital copying, scanning, recording, or otherwise, except as specifically authorized.

Brush Education Inc.

www.brusheducation.ca

Design and layout: Carol Dragich, Dragich Design; Cover image: iStock: Dominik Pabis.

Proofreading: Shauna Babiuk.

Figure credits: Photos used courtesy Bruce Timothy Keith: 1.11.5, 2.1, 8.3, 8.8, 8.9. Image of proof page (7.4) courtesy Bruce Peel Special Collections & Archives, University of Alberta. istock/focusstock: 8.15. Courtesy Webcom: 8.16. Illustrations by Chao Yu, Vancouver: 8.10, 8.12, 8.188.22.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Vermeer, Leslie, 1969-, author The complete Canadian book editor / Leslie Vermeer.

Includes bibliographical references and index. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-1-55059-677-9 (paperback).--ISBN 978-1-55059-678-6 (pdf).-- ISBN 978-1-55059-679-3 (mobi).--ISBN 978-1-55059-680-9 (epub)

1. Editing. 2. Publishers and publishing--Canada. 3. Book industries and trade--Canada. I. Title.

PN162.V47 2016070.5'1C2016-903926-9C2016-903927-7

Why Edit Books?

When you read a book, you hold anothers mind in your hands.James Burke

Why do you want to be a book editor? One of the reasons many people are attracted to book editing is the allure of authors. What editor wouldnt want to meet the next J.K. Rowling, an up-and-coming Margaret Atwood, a Joyce Carol Oates in the making? Another attraction is the physicality of books themselves and what they contain. Around the globe, humans have invested books with a special significance, both for the ideas they present and for the cultural values they represent.

What Is a Book?

Simply put, books are storehouses for information and narratives of variouskindswhatever a culture deems to be valuable. Books as objects have existed for severalthousand years, although not always in forms that people today would recognize as books. For our purposes today, a book is a gathering of sheets bound together in some manner (such as by sewing or with glue) and protected by a , possibly including a spine; this definition of book reflects the codex, which dates from the early Common Era. The codex is what most people think of when they visualize a book, and it is to the codex that most people refer when we contemplate the concept of bookness, or an objects likeness to a generic book structure.

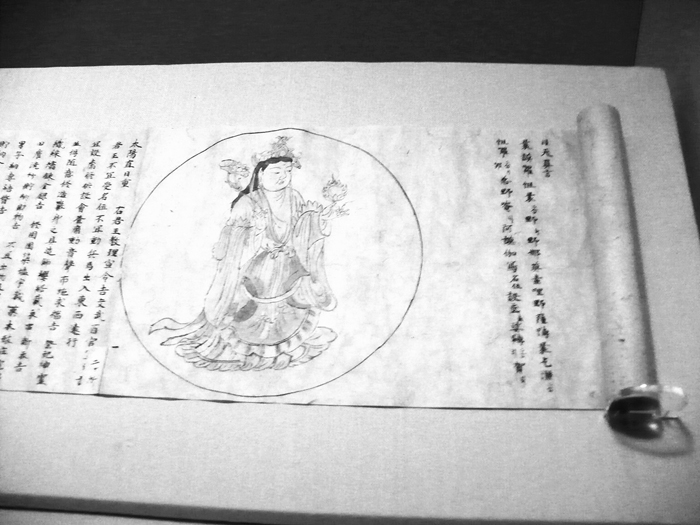

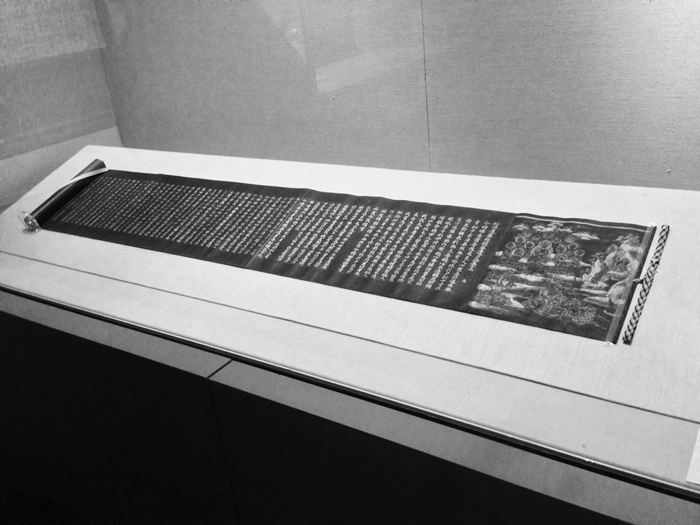

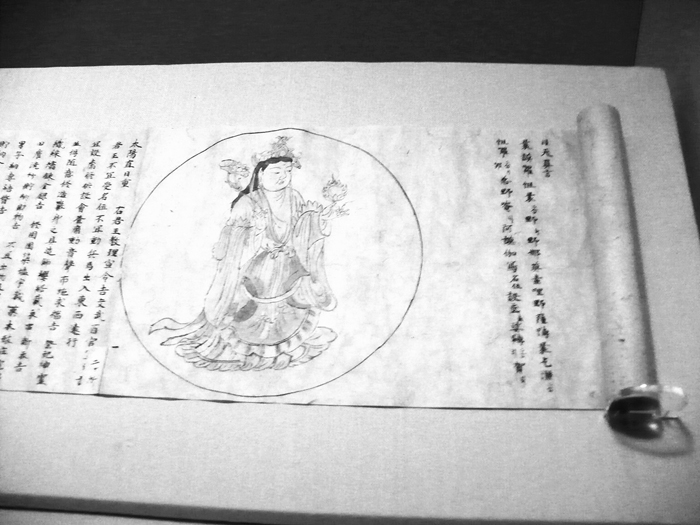

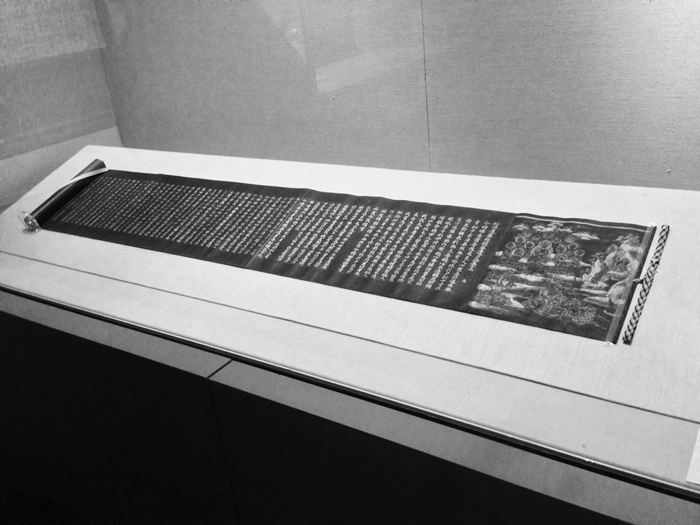

Prior to the development of the codex, and for centuries after it, too, books were produced in the form of scrolls. The significance, and

Figure 1.1 A Japanese scroll book, ca. 1125, showing detail from The Secrets of the Nine Luminaries, a text that explains aspects of the sun, moons, and planets

Figure 1.2 A twelfth-century Japanese handscroll from the Lotus Sutra

Yet whether we consider a collection of clay tablets a book or not is relevant today, when many commentators argue that the experience of consuming text from a screen is qualitatively different from consuming text from bound paperthat is, that an ebook isnt a book because of how it is used, regardless of the text it contains. For many people, the physical object of the bookthe paper, glue, and inkis what matters, not the structure of the text or its provision of information or story. People who read ebooks often respond to the evocation of the paper book with a strongly defensive tone; ebook readers are frequently accused of disliking books, or of not being real readers, whatever that may mean. And we might look to the way in which dedicated ereading devices have been manufactured to emulate the experience of conventional book-in-hand readinga clear evocation of bookness. What a book isand relatedly, what kinds of reading are valuable and what kinds are notis a highly contentious question at this moment in our society, as we stand ready to embrace, or reject, the transformation of the book in a digital world.

Questions of what is and is not a bookmuch like questions of what is and is not publishabledepend on privilege and authority: who gets to decide? That notion is something you should keep in mind as you work through this text: books are a technology of privilege. For most of human history, most people could not write or read; and until the last few decades, the ownership of multiple books was restricted to a relatively small group of people. Even today, many millions of people in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and other Western nations cannot afford to own books. That there are books in so many formats that we can argue about themthat there are books to edit at allis an outcome of our societys tremendous privilege, something we ought not to take for granted.

A book is both a physical and an abstract thing. Many writers are encouraged by thenotion that they have a book in themin which case we are obviously not talking about aphysical glue-and-paper object. And most of us would distinguish ourbooksthe books we personally own and cherishfrom the masses of otherpeoples books, as well as from the unpurchased books stocked in bookstores. Digital books add a new dimension to our mutable sense of the bookalthough some people would say digital books also erase elements of the book. Since the late nineteenth century, scholars have been studying books as objects that transmit specific information about a culture and its meanings, examining the process of manufacturing, circulating, reading, and preserving both books in general and specific successful, readers should ideally lose themselves in the books content, experiencing the physical book almost invisibly, yet the physical book is still there. Our preferences and judgements for and against various editions precede and emerge from our actual experiences of reading and using text. As book editors, we have these experiences of text ourselves and in turn produce them for others.

My purpose in this text is more practical than academic, but you should keep these points in mind. The book as the West has known it for some five hundred years is changing, and these changes are pushing Western society to ask important questions about who we are, how we communicate, and what we value. Books represent a portable visual record of information and narrative for future generationsbut somehow thats not all they are, either, even from the most crassly commercial point of view.