Howard Axelrod - The Stars in Our Pockets: Getting Lost and Sometimes Found in the Digital Age

Here you can read online Howard Axelrod - The Stars in Our Pockets: Getting Lost and Sometimes Found in the Digital Age full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Beacon Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Stars in Our Pockets: Getting Lost and Sometimes Found in the Digital Age

- Author:

- Publisher:Beacon Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Stars in Our Pockets: Getting Lost and Sometimes Found in the Digital Age: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Stars in Our Pockets: Getting Lost and Sometimes Found in the Digital Age" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The human brains ability to adapt has been an evolutionary advantage for the last 40,000 years, but now, for the first time in human history, were effectively living in two environments at once--the natural and the digital--and many of the traits that help us online dont help us offline, and vice versa. Drawing on his experience of acclimating to a life of solitude in the woods and then to digital life upon his return to the city, Howard Axelrod explores the human brains impressive but indiscriminate ability to adapt to its surroundings. The Stars in Our Pockets is a portrait of, as well as a meditation on, what Axelrod comes to think of as inner climate change. Just as were losing diversity of plant and animal species due to the environmental crisis, so too are we losing the diversity and range of our minds due to changes in our cognitive environment.

As we navigate the rapid shifts between the physical and digital realms, what traits are we trading without being aware of it? The Stars in Our Pockets is a personal and profound reminder of the world around us and the worlds within us--and how, as alienated as we may sometimes feel, they were made for each other.

Reviews:

Poetic, ruminative, and never preachy, this book is a game changer for readers who yearn to see beyond 240 characters. Booklist, Starred Review

A provocative inquiry . . . Refreshingly, Axelrod doesnt deliver a screed against cybertechnology but rather a series of philosophical meditations on the consequences of connecting ourselves digitally to the point where the realm of the screen is a world unto itself. Kirkus Reviews, Starred Review

Axelrod provides powerful arguments against todays all-encompassing digital world in this concise and insightful meditation. Publishers Weekly

About the Author:

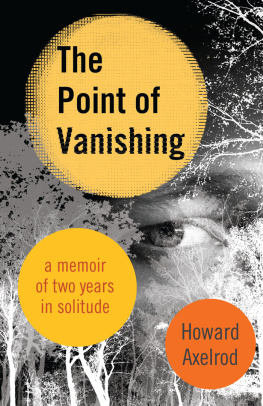

Howard Axelrod is the author of The Point of Vanishing: A Memoir of Two Years in Solitude, named one of the best books of 2015 by Slate, the Chicago Tribune, and Entropy Magazine , and one of the best memoirs of 2015 by Library Journal. His essays have appeared in the New York Times Magazine, O Magazine, Politico, Salon, the Virginia Quarterly Review, and the Boston Globe. He has taught at Harvard, the University of Arizona, and is currently the director of the Creative Writing Program at Loyola University in Chicago. Connect with him at howardaxelrod.com.

184 pages

Publisher: Beacon Press (January 14, 2020)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0807036757

ISBN-13: 978-0807036754

Howard Axelrod: author's other books

Who wrote The Stars in Our Pockets: Getting Lost and Sometimes Found in the Digital Age? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.