Acknowledgments

Gratitude is the happiest form of debtthe accounts are incalculable, and the only way to square them is by trying to do good work and by trying to be generous in the ways others have been generous to you. In other words, I will forever be working to repay:

My family: Mom, Dad, and Matt, all of whom supported this book without knowing what was in it, which means, really, that they supported me. The years the book contains, and the years it took to write, werent easy on any of us, and their love helped me more than I can say.

My early mentors: Robert Coles and Ron Carlsonfor their examples, their profound decency, and their encouragement. Thanks also to Alison Hawthorne Deming, Jane Miller, Steve Orlen, Boyer Rickel, and everyone at the University of Arizona MFA program.

The residencies where I wrote so much of the book: Ucross, Blue Mountain Center, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, Kimmel Harding Nelson, the Anderson Center, the Norman Mailer Center, Hambidge, and the Vermont Studio Center. Special thanks to Harriet Barlow, Ben Strader, Ruth Salvatore, Sharon Dynak, and Gary Clark.

My early readers, for their insights and their belief in the project: Susan Choi, David Ebershoff, Albert LaFarge, Caryn Cardello, Julie Bloemeke, Cornelius Howland, Jill Gallenstein, Aaron Goldberg, Leah Gillis, Peter Derby, Chris Boucher, Katherine Cohen, and Aaron Richmond.

My later readers: Tanya Larkin, Helena de Bres, and Mary Marbourg, for their keen intellectual responses to the ideas and their deeply felt personal responses to the emotions.

The community: everyone at Grub Street, especially Chip Cheek, Chris Castellani, Sonya Larson, Alison Murphy, Sean Van Deuren, Lauren Rheaume, and to James Scott for bringing me into the fold. To my memoir students, who, through their own writing, reminded me of what memoir can do. And to my students at the University of Arizona, Wentworth Institute of Technology, and Framingham State, whose questions about the book helped me understand the story I was telling. And to my WIT colleagues: Devon Sprague, Max Grinnell, and Loren Sparling.

For behind-the-scenes understanding and guidance: Linda Madoff, Jami Axelrod, Alicia Pritt, Jodi Heyman, Shuchi Saraswat, Jaime Clark, Mary Cotton, Bill McKibben, Wendy Wakeman, Vicki Kennedy, Doris Cooper, Katherine Fausset, Leslie Jamison, Adelle Waldman, David Macmillan, and Bill Hayes. And to Sophie Barbasch, for the photograph and for all the great cartoons.

A special thank-you to Anne LeClaire, for reading an early draft and believing in it enough to introduce me to her agent, Deborah Schneider, and to Bella Pollen, for being such a kind and generous reader.

And to Oliver Sacks, for his insight, his kindness, and for giving the book the highest compliment it could possibly receive.

To Charles Bock, for guiding me through every stage, including that talk in Central Park before my meetings with agents and for being such a smart and abiding friend. A mensch in every possible way.

To Deborah Schneider, my superhero agent, who saw the book I was writing even when I couldnt and who always knew how and when to fight. She was the fearless advocate this project needed, and she earned my trust in hundreds of ways. Thanks also to Victoria Marini and to everyone at Gelfman Schneider/ICM Partners and Curtis Brown in London.

To Alexis Rizzuto, my editor, for her immediate and intuitive understanding of the book and for her tireless attention to detail. Also, to Helene Atwan, Tom Hallock, Rob Arnold, Will Myers, and the whole team at Beacon Press. Im so proud to be on the Beacon list.

To Ray Hearey, who I thought of so often while writing and whose friendship was always with me, even from across the country.

To Andrew Rueb, a true friend through everything. For all the dinners, all the talks, all the faith. And for all the understanding, without needing to read a word.

And, lastly, one more thank-you to my parents. This book, in so many ways, is for you.

1

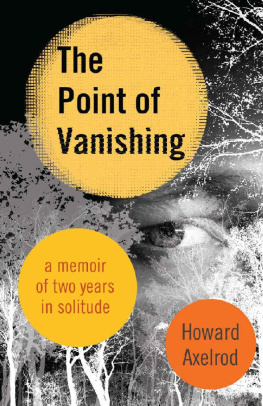

It felt like a homecoming. It didnt matter that a thunderstorm was raging, the rain drumming on the tar-paper roof, gunpowder flashes lighting up the dense, dripping foliage behind the house. It didnt matter that I hadnt stocked up yet at the C&C, so my dinner was only a piece of toast with melted cheese. And it didnt matter that Boston was hundreds of miles awayand had stopped feeling like my home years earlier. My one frying pan sat on the stove. My two forks, two knives, and two spoons were installed in the drawer by the sink. My sweaters, wool socks, and snowpants were unpacked on the plywood shelves upstairs. And outside, at the top of the steep dirt grade, my little white Honda sat empty. I pictured it like a pack horse finally unburdened, its body wild and calm with relief. It had known some beautiful pastures since my college graduation three years earlierelk plodding through a drifting snow in the Grand Tetons; the mesa late in the day gone ochre and purple above the Rio Grandebut for the first time, it would be in one place longer than four months. There would be no need to leave, no need to pack my bags again, no need to search elsewhere. Lev, the owner of the house, wouldnt be back until June. Finally, I could allow myself not to be an outsider, to belong to the land.

Id found the house by posting handwritten signs across northern Vermont, on the quilt-like bulletin boards outside general stores, on the musty walls inside laundromats, in Peacham, Johnson, Jay, in Barton, Newport, and Morrisville, and even in one town called Eden. My attempt at respectable handwriting hung there beside the firewood for sale, the beloved lost cats, the spaghetti dinners already weeks gone: Wanted: a cabin or house set in the woods, with good light, very solitary. Proximity to a stream or brook. Running water and electricity preferred. Only one man had replied. Lev was a philosophy professor, leaving in September to teach in his native Tel Aviv. Hed bought the house the previous summer and was refurbishing it. In August, I made the six-hour drive from Boston, and Lev took me on a tour, pointing out his meager renovations. He was surprisingly tall, with a reddish beard and restless hands. It was hard to see the house through his talking. Hed planned to take sabbaticals with his wife, but after one winter of solitude for two, they were divorcing. Hed never lived in the house alone. He said he greatly anticipated such a winterGod only comes to those who are alone, he saidbut it was obvious from his combination of bluster and warning that he viewed me as a guinea pig. I didnt mind; the guinea pig rate was good. Id only have to pay for six cords of firewood, electricity, and a bit of propane for the hot-water heaterless than one thousand dollars all told.

From the outside, the house resembled a battered pirate ship run aground. A glass look-out tower, small slanting decks with sagging wooden railings, a catwalk along the second story, its two planks noticeably bowed. Doubling as the hold was a makeshift garagea corrugated steel roof sloped over a dirt floor, the berths not large enough for cars but well-suited for storing firewood. Inside, through the mudroom, the main room was no less jerry-riggedthe lightbulb above the table exposed, half the floor plywood, half faux-wood flooringbut it wasnt a cave, wasnt damp or dark. There were three floor-to-ceiling windows offering a kind of triptych of the woods. There was a refrigerator, an electric stove, a toaster oven. There was a woodstove for heat. Up a steep set of wooden stairs was the bedroomwith wide wood floorboards, a sloping ceiling, and a mattress in the corner. On the far side of the mattress was Levs pride and joy: a small raised office space, with a desk and commanding view of the Green Mountains. The window looked out above one of the pitched and beaten decks. The green hills retreated into the distance like cresting waves.