For Anita and for Ian

Contents

Acknowledgments

Both author and reader have had the good fortune to benefit from the work of two great editors, Rob Kirkpatrick at Thomas Dunne Books and copyeditor India Cooper. The first helped shape Savage Empire and the second redeemed it from any number of mysteries and outright errors. On behalf of readers, the author thanks them.

OVERTURE

Mr. Pepyss Hat

S AMUEL PEPYS WAS JUST the kind of Englishman the English themselves cherishextraordinary in his ordinariness. While he rose high above his humble birth, he avoided doing so with any spectacle or flamboyance. For this reason, among others, his celebrated Diary, which he began on January 1, 1660, and stopped in May 1669, after his eyesight went bad, is truly representative of London life during a decade both extraordinary and ordinary.

He wrote about both. He wrote about the Great Plague and the Great Fire, and he also wrote about his hat. Obviously, plague and fire are extraordinary, but Pepyss hat, as it turns out, was not so ordinary a subject as it may at first seem. If plague and fire brought mass death, Pepyss hat was the very stuff of mass deathand also boundless ambition, great enterprise, profoundly consequential discovery, and, in the end, epoch-making revolution.

* * *

Samuel Pepys was born in London on February 23, 1633, to a tailor father and to a mother who was the daughter of a Whitechapel butcher. Although his corner of the family got their living by trade, his father did have a socially prominent cousin, Richard Pepys, who became a member of Parliament, Baron of the Exchequer, and Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, and whose influence was doubtless crucial to enrolling young Pepys in Huntingdon Grammar School in 1644, and then in St. Pauls School two years later. Sooner or later when one Englishman meets another, the question will be asked: What school did you attend? With Huntingdon and St. Pauls behind him, the young mans rise commenced.

In 1649, Samuel Pepys witnessed a momentous occurrence, the beheading of a king, Charles I, but so did many other Londoners, which made this event less extraordinary than it might otherwise have been. Two years later, he enrolled in Magdalene College, Cambridge, and was awarded a bachelor of arts degree in 1654. Shortly after his graduation, Pepys went to live with another of his fathers prominent cousins, Sir Edward Montagu (who would soon be created first Earl of Sandwich), and brought into the Montagu household fourteen-year-old Elisabeth Marchant de Saint-Michel, whom he married in 1655.

No doubt, marriage was for Pepys a major event, as it is for everyone who marries, but even more momentous in his life at this stage was the removal of a bladder stone on March 26, 1658, in a harrowing surgery without either anesthesia or antisepsis and therefore with very little prospect of a happy outcome. That he lived through the ordeal and recovered was a fact he understandably celebrated lifelong. Later in the year, Pepys began his professional career, moving from the Montagu home to Axe Yard (near modern Downing Street), where he became a teller in the exchequer. From this position, thanks to the patronage of Sir Edward, he rose to become Clerk of the Acts to the Navy Board in 1660essentially secretary to the Navy Board, a key administrative post. His salary of 350 was munificent indeed, and it was in 1660 as well that he commenced his diary.

* * *

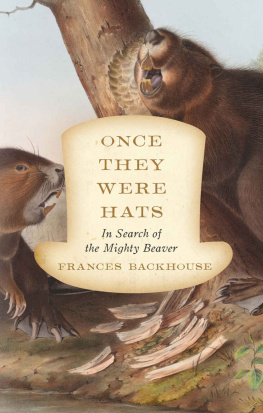

Much of great moment occurred during the decade in which he kept the diary. There was the Second Dutch War (166567), of nearly ruinous cost in men and money, both to England and Holland; the Great Plague of 1665, which carried off some hundred thousand people, a fifth of the capitals population; and, in 1666, the Great Fire of London, which razed seventy thousand of the eighty thousand buildings in Pepyss own haunt, the central City of London. As an intimate window onto these events, Pepyss Diary is of inestimable value, yet the legions of historians and enthusiasts who have pored over the nine volumes of the published book treasure it less as a picture of extraordinary cataclysm than as a chronicle of the strictly quotidian, as when, for example, on Tuesday, October 29, 1661, Pepys recorded how he prepared to attend my Lord Mayors feast by putting on my half cloth black stockings and my new coat of the fashion, which pleases me well, and my beaver. It was only with the addition of the latter that Pepys deemed himself ready to go.

By beaver, Pepys meant his hat, but not just any hat. It was a hat suited to the wardrobe of a prosperous gentleman, to a personage worthy of an invitation to my Lord Mayors feast. Pepyss patron, Montagu, had earlier in the year suffered the misfortune of having had his beaver stolen, a mishap made the more vexing to him because the thief had had the temerity to leave an ordinary hat in its place! In his entry of June 27, 1661, Pepys recorded that Joseph Holden, a haberdasher of Bride Lane (a London street noted for its fine mens furnishers), sent me a bever, which cost me 4 l . 5 s. This figure alone explains Montagus vexation, for an ordinary hat of felted fabric, presumably the kind left by the thief, could be had for a mere thirty-five shillings.

The historical value of money is notoriously difficult to calculate realistically, but consider that Pepys earned 350 from his job on the naval board, deemed at the time a very handsome salary, and had shelled out more than 1 percent of that yearly income for a mere hat. What did other things cost in Pepyss day? Some detailed figures can be found in a Statement taken before Charles Talber for Hugh May, Esq., Clerk of the Markets to His Majestys Household, on August 21, 1625:

A kilderkin [18 gallons] of good ale or double beer with carriage [delivery charges]. | 3 s 4 d |

A full quart of the best ale or beer by measure sealed. | 1 d |

A full quart of single ale or beer by measure sealed. | d |

A full pound of butter sweet and new the best in the market. | 3 d |

A pound of best cheese in the shop or market. | 2 d |

A stone [8 pounds!] of the best beef at the butchers. | 1 s 2 d |

A hundred good oak boards with carriage. | 8 s |

A hundred good elm boards with carriage. | 6 s |

One thousand bricks. | 14 s |

An accounting from 1630 listing the cost of emigration from England to New England put the expense of four pairs of new shoes (or one pair of mens boots) at nine shillings. So: four pounds, five shillings for a hat ? Must have been some hat.

On Saturday, April 26, 1662, the diarist recorded a very pleasant outing to Southampton, where he toured Lord Southamptons parks and lands, then had dinner with the mayor. In all, Pepys could think of only two causes for complaint. First: While his meal of sturgeon had been well prepared, the caviar he was served was neither salt[ed] enough, nor [were] the seedes of the roe broke, but [were] all in berryes. Second: After dinner to horse again, being in nothing troubled but the badness of my hat, which I borrowed to save my beaver.

Consider the second complaint closely. So highly did Pepys value his beaver hat that he borrowed an embarrassingly bad substitute for it so that he would not have to hazard his own elegant headgear on a day trip just outside of London.