1616

The World in Motion

1616

The World in Motion

Thomas Christensen

COUNTERPOINT

BERKELEY

Title page frontispiece (pp. 23): Arrival of a Portuguese Ship, early seventeenth century (detail). Japan. Folding screen, one of a pair; ink, colors, and gold on paper, 333 173 cm (overall). Asian Art Museum, The Avery Brundage Collection, B60D77+.

See p. 68 for more of the screen.

Hardcover edition endsheets: Four Large Cities of the World (top) and Map of the World (bottom), 16101620. Japan. Pair of eight-panel screens; ink color, and gold on paper, each 478 159 cm. Kobe City Museum.

These two large screens, conceived as a set, incorporate new geographical information brought to Japan by Portuguese and Dutch visitors; at the same time they reveal a greater knowledge of Japan (shown at an exaggerated size) and East Asia than was available to Europeans. As a result they represent some of the most sophisticated geographical knowledge of the early seventeenth century.

Two of the six circular insets show a solar and a lunar eclipse, reflecting the importance of astronomical observation during the period (see Witch Hunters and Truth Seekers, p. 187). The other insets show the arctic and antarctic poles, and globes centered on Japan and Brazil, which were considered antipodes. Four major cities of the Mediterranean region are depicted: Lisbon, home to the Portuguese sailors who traveled east to Asia around the Cape of Good Hope; Seville, home to the Spanish who traveled west to America and on from there to Asia; Rome, center of the Catholic religion; and Istanbul, representing the realm of Islam.

In captions dimensions are rounded to the nearest centimeter. Width is given before height.

Archaic spelling is sometimes retained in period quotations to give the flavor of the time.

Copyright by Thomas Christensen 2012

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available

ISBN: 978-1-61902-046-7

COUNTERPOINT

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

| Book design by the author

www.rightreading.com |

Permission credits appear on p. 379, which constitutes a continuation of this copyright page.

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Motion and transformation take place in both quality and quantity in the very substance of things.

Mulla Sadra (ca. 15711641), Persian philosopher

I will direct my mind to the human breast, and to the heart itself, and see how it is driven by perpetual motion for as long as life remains; for life ends when the motion is taken away, damaged, or hindered. It is natural therefore for man to move from place to place, from region to region, until he can see into himself, above himself, and around himself.

Michael Maier (15691622), German physician, alchemist, author

This book is for Carol, Claire, Ellen, Verle, and Anne

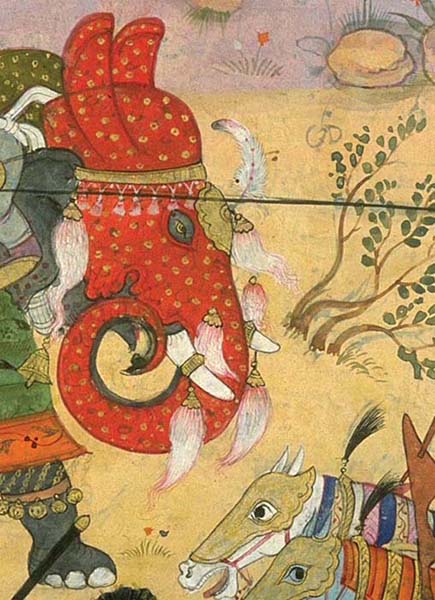

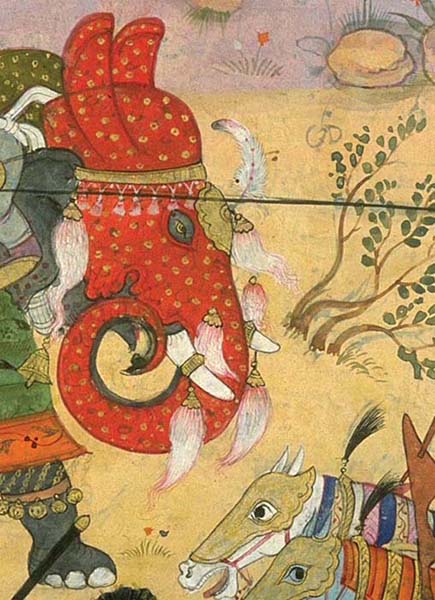

Karna, one of the Kauravas, Slays the Pandavas Nephew Ghatotkacha with a Weapon Given to Him by Indra, the King of the Gods, from a Manuscript of the Razmnama (detail), 16161617. India, perhaps Burhanpur, Madhya Pradesh state. Ink, opaque watercolors and gold on paper, 23 33 cm. Asian Art Museum, Gift of the Connoisseurs Council with additional funding from Fred M. and Nancy Livingston Levin, the Shenson Foundation, in memory of A. Jess Shenson, 2003.6.

The Razmnama is a Persian translation of the Mahabharata, one of the great Hindu epics.

Contents

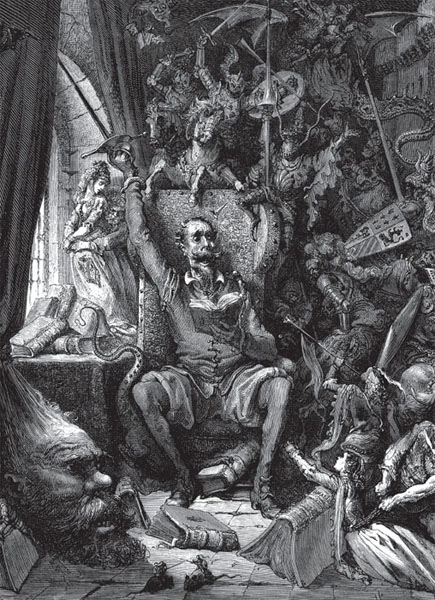

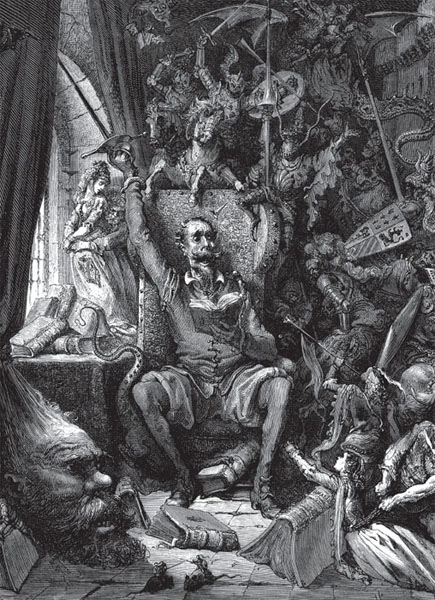

Don Quixote Driven Mad by Reading, by Gustave Dor. Illustration for Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes, 1863. Hachette and Co., Paris. Engraving.

One morning in September 2009 I woke up in my bedroom in the San Francisco Bay Area with the date 1616 in my head and the resolution to research and write about that year already formed. It was a strange resolve in many ways, not just because it seemed to come from nowhere. My academic training had been in literary modernism and postmodernism, and my professional work had centered around trade book publishing, literary translation, and the design and production of museum art catalogues. Nevertheless, from that day on I researched that year with a single-mindedness that bordered on obsession.

Some years 1066, 1492, 1776, 1945 are so associated with momentous events that they are emblazoned in everyones consciousness. The year 1616, despite such notable developments as those this book chronicles, is, for the most part, not one of these. This seems to me a good thing. Cathartic events can so dominate an era that they make it difficult to see the deeper forces that drive long-term change. In 1616, on the other hand, it is possible to make out intimations of modernity in developing globalism, militarism, imperialism, diasporism, colonialism, capitalism, rationalism, bureaucratization, urbanization, individualism, and so on.

I was vague on historical developments during this period in many parts of the world, but I knew one thing about the year from the outset. On April 23, 1616, two literary giants, William Shakespeare and Miguel de Cervantes, accomplished the feat of dying on the same date but different days. Mainly for the reason of their shared date of death, the United Nations named April 23 the international Day of the Book.

Shakespeare, seven years the younger, went first, on Tuesday. Miguel de Cervantes, despite a life of hardship, held on another week and a half, until Saturday. This was possible because Spain had adopted the Gregorian calendar proposed in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII. Britain, however, recoiling at any whiff of papism, did not adopt the new calendar until 1752, and it lagged, in 1616, ten days behind. Although Shakespeares death date is traditionally given as April 23, according to the new calendar he would have died on May 3.

At that time there was as little agreement about when the year began as about what day it was. In many parts of Europe it had been traditional to consider a date such as Annunciation Day the day nine months before Christmas when it was revealed to Mary that she would bear a child as the beginning of the year; standardizing on January 1 was a newfangled notion based on an ancient tradition, the Roman consular year. The European states adopted the new date for the new year each in its time: Venice in 1522, Spain in 1556, France in 1564, Scotland in 1600, Russia in 1700, and so on. The January 1, 1616, masque that is the focus of the following section of this book would have been thought of by Londoners of its time as falling in the eleventh month of 1615.

Next page