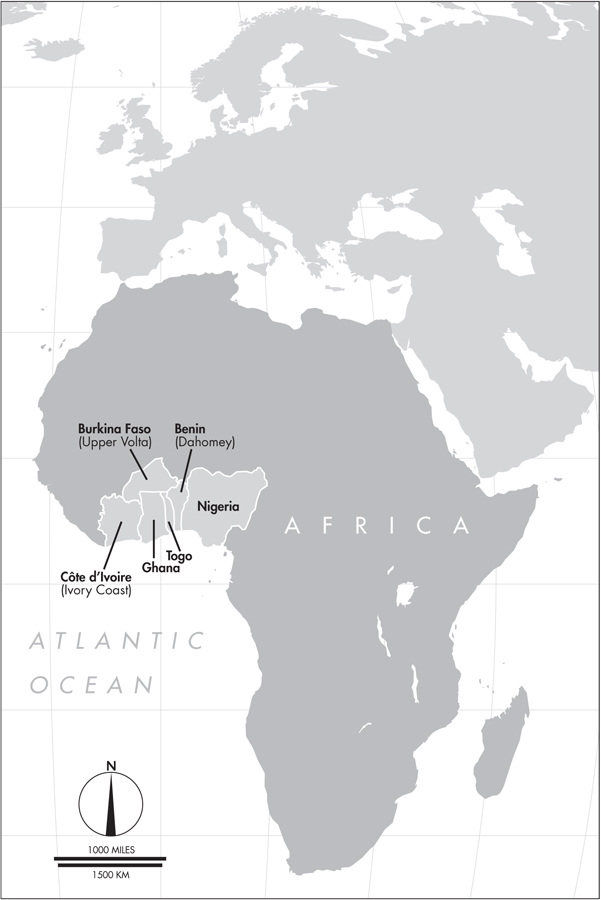

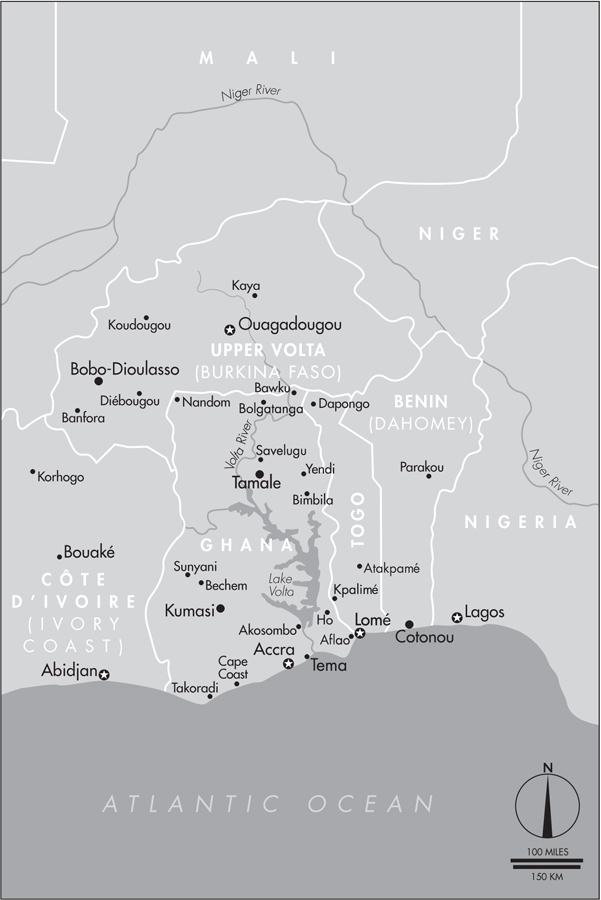

JOHN M. CHERNOFF is the author of Hustling Is Not Stealing: Stories of an African Bar Girl (2003) and African Rhythm and African Sensibility: Aesthetics and Social Action in African Musical Idioms (1979), both published by the University of Chicago Press. Chernoff spent more than seven years in West Africa, based in Accra and Tamale, Ghana, where he also studied popular music and the music and culture of the Dagbamba people. His recordings of Dagbamba music include Master Fiddlers of Dagbon and Master Drummers of Dagbon, volumes 1 and 2.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2005 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2005

Printed in the United States of America

14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN: 0-226-10354-4 (cloth)

ISBN: 0-226-10355-2 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-226-07479-5 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chernoff, John Miller

Exchange is not robbery : more stories of an African bar girl / John M. Chernoff.

p. cm.

Continuation of Hustling is not stealing.

ISBN 0-226-10354-4 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 0-226-10355-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. WomenGhanaSocial conditions. 2. WomenTogoSocial conditions. 3. WomenBurkina FasoSocial conditions. I. Chernoff, John Miller. Hustling is not stealing. II. Title.

HQ1816.C47 2005

305.42'0966dc22

2004010381

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Exchange Is Not Robbery

MORE STORIES OF AN AFRICAN BAR GIRL

John M. Chernoff

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

Chicago and London

For my wife Donna, my daughters Eunice and Eva, and my sons Harlan and Avram

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the Joint Committee on African Studies of the Social Science Research Council and the American Council of Learned Societies for a Postdoctoral Fellowship for African Area Research that helped me to develop some of the data for this book. I would also like to thank the following people for reading and commenting on drafts or for helping with various aspects of this book: Abraham Adzenyah, Emmanuel Akyeampong, Marianne Alverson, Kelly Askew, Deborah Benkovitz, John Berthelette, Willem Bijlefeld, Kenneth Bilby, David Brent, Alan Brody, Jason Brown, David Byrne, Amina Jefferson Bruce, Donna Chernoff, Harold Chernoff, Michael Chernoff, Richard Closs, Ben DeMott, Peter Edidin, Mark Ehrman, Kai Erikson, Steven W. Evans, Alan Fiske, Steven Friedson, Arnold Gefsky, Les Getchell, Dawn Hall, Maxine Heller, Kissmal Ibrahim Hussein, Angeliki Keil, Charles Keil, Bruce King, Sarah LeVine, David Light, Rene Lysloff, Yao Hlomabu Malm, Michael Mattil, Leighton McCutchen, Will Milberg, David Mooney, Mustapha Muhammed, Steven Mullen, Judy Naumburg, Deborah Neff, Samuel Nyanyo Nmai, E. F. Ofosu-Appeah, Timmy W. Ogude, James Peters III, Charles Piot, Dina Light Ranade, Carl Rollyson, Marina Roseman, Eric Rucker, Nadine Saada, Philip Schuyler, Paul Stoller, Deborah Tannen, Robert F. Thompson, Richard Underwood, Christopher Waterman, Andrew Weintraub, and David Wise. Betsy Morgan DeGory assisted with the research and contributed many ideas to the work. The following people provided technical assistance on writing the various languages in the text: Eric O. Beeko, J. H. Kwabena Nketia, Lilly Nketia, and Joseph Adjaye for Asante Twi; Kathryn Geurts, Kojo Amegashie, and Felix K. Ameka for Ewe and Mina/Gen; Beverly Mack and John Hutchison for Hausa; Philip Schuyler for Arabic; Paul Stoller and Jean-Paul Dumont for Verlan and French argot; Joachim Zabramba for Moore; Joachim Zabramba, Patricia Koutaba, and John Hutchison for Dioula. And, of course, I would like to thank the woman who is called Hawa in this book and also all the people in Ghana, Togo, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, and other West African countries who helped me understand their world as they know it.

The one who holds a rope knows its joining places and its weak points, but the one who wove the thread is the one who knows how long it is.

DAGBAMBA PROVERB

West African locations mentioned in Hawas stories

PROLOGUE

Exchange Is Not Robbery is the continuation of Hustling Is Not Stealing. Together, the two books portray West African urban life from the perspective of a brilliant but uneducated African woman as she reviewed her experiences from her childhood into her twenties. Named Hawa in these books, she was a virtuoso storyteller, but instead of narrating indigenous folk tales on moonlit village evenings, she used her storytelling to entertain her friends around the cooking pot and at the drinking bars with dramatized anecdotes that resonated with their everyday lives. I met her in 1971 in Accra, Ghana, and I maintained our acquaintance after she moved to Togo and then later to Burkina Faso.

Exchange Is Not Robbery contains many flashbacks to Hawas youth but not a recapitulation of her circumstances. She was born in Ghana in the early 1950s, where her family had migrated from Burkina Faso, then known as Upper Volta. Based in Kumasi, her father worked on cocoa farms and traded. Her mother died when Hawa was very young, and she was raised in various homes within her fathers and mothers extended families, often moving from place to place because she rejected whatever she saw as exploitative or abusive treatment. In the opening passages of Hustling Is Not Stealing, she describes herself as a letter posted here and there. She was given in marriage as a teenager to a man who had two other wives, but she left her husbands house after quarreling with a senior wife. Her father refused to allow her to return to the family, and at the age of about sixteen she began an independent life in Accra as an ashawo, an unmarried woman dependent on men outside of a family setting.

The Introduction to Hustling Is Not Stealing describes several aspects of the postcolonial West African scene that present significant barriers to outsiders hoping to understand the cultural context Hawa portrays. What many Westerners know about Africa is still mediated by alienating mythic images, whether romantic, exotic, barbaric, or chaotic. Those images are further filtered and augmented by the publications of experts and scholars about the tangled processes of modernization. Sleeping tablets for elephants, an educated Ghanaian friend called the publications. They should be sold to zoos. The statistics are dismal, and the situations they represent everywhere seem to range from desperate to disastrous. Despite their frequently narrow focus, the scattered media reports, the fragmentary academic studies, and in their own way even the novels of the educated elite, all have ambitions to elevate generalizations about big social issues. It is difficult to get an idea of what life is like at ground level or to get a feeling for the experience of people who live there. As I noted in that Introduction, if one were able to read everything written about Africa, the only thing one would know for sure is that on the whole continent, nobody is having any fun.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.