The Great War and Modern Memory

Other Books by Paul Fussell

Theory of Prosody in Eighteenth-Century England

Poetic Meter and Poetic Form

The Rhetorical World of Augustan Humanism:

Ethics and Imagery from Swift to Burke

Samuel Johnson and the Life of Writing

Abroad: British Literary Traveling Between the Wars

The Boy Scout Handbook and Other Observations

Class: A Guide through the American Status System

Thank God for the Atom Bomb and Other Essays

Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War

BAD: or, The Dumbing of America

The Anti-Egotist: Kingsley Amis, Man of Letters

Editor

English Augustan Poetry

The Ordeal of Alfred M. Hale

Siegfried Sassoons Long Journey

The Norton Book of Travel

The Norton Book of Modern War

Co-Editor

Eighteenth-Century English Literature

PAUL FUSSELL

The Great War and Modern Memory

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Oxford University Press 1975, 2000, 2013

First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 1977

ISBN for 2013 edition: 978-0-19-997195-4

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the first edition as follows:

Fussell, Paul, 1924

The Great War and modern memory / Paul Fussell.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Contains a new afterword.

Includes bibliographic references and index.

ISBN 0-19-513332-3 (pbk.)

0-19-513331-5

1. English literature20th centuryHistory and criticism.

2. World War, 1914-1918Great BritainLiterature and the War.

3. Memory in literature. 4. War and literature.

PR478.E8F8. 2000 8209358dc21 99-43295

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

To the Memory of

Technical Sergeant Edward Keith Hudson, ASN 36548772

Co. F, 410th Infantry

Killed beside me in France

March 15, 1945

Contents

I FIRST MET PAUL FUSSELL EN ROUTE TO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE IN Germany in the late 1970s. We were heading by car to a meeting on War Enthusiasm in 1914, a reaction to war we both detested, and I noticed that whenever we reached a crossroads, or passed a hill, Paul would scan the horizon in a quick and methodical manner. After an hour or so, I asked him what he was looking for. He said it was a reflex from his army duty he still could not change. Whenever he passed a point of interest, he scanned the landscape for the best place to put an anti-tank gun. His daily journey home on Route 1 in New Jersey, he said, provided many such opportunities to scan the landscape for good defensive positions. This was, he added, one of the ways in which he was still stuck in the Battle of the Bulge, which had left him with a piece of shrapnel in his thigh and a cosmic skepticism about the arbitrariness of survival in war. His wartime service did more than that. It helped make him one of the finest scholars of his generation.

Fussell was a great historian, one who found a way to turn his deep, visceral knowledge of the horrors and stupidities of war into a vision of how to write about war. I use the term historian deliberately, though he professed literature throughout his academic career. What he accomplished, not singlehandedly, although centrally, was to break down the barrier between the literary study of war writing and the cultural history of war. When he published The Great War and Modern Memory in 1975, he set in motion what is now an avalanche of books and articles of all kinds on the First World War. He did much to create the field in which I have worked for the last four decades.

How did he do it? By using his emotion and his anger to frame his understanding of memory, and his insight into the way language frames memory, especially memories of war. War, he knew, is simply too frightful, too chaotic, too arbitrary, too bizarre, too uncanny a set of events and images to grasp directly. We need blinkers, spectacles, shades to glimpse war even indirectly. Without filters, we are blinded by its searing light. Language is such a filter. So is painting; photography; film. The indelible imprint Paul Fussell left on our understanding of war was on how language frames what he termed modern memory.

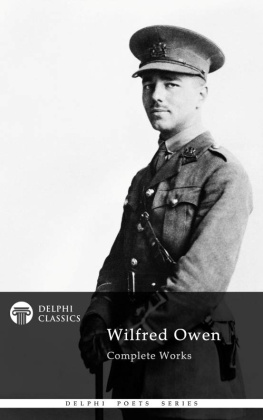

The term is seductively simple but essentially subtle and nuanced. Fussell meant that through writing about war, First World War veterans left us a narrative framework we frequently overlook. Drawing on the literary scholarship of the Canadian critic Northrop Fry, he made these distinctions. Instead of viewing war as epic, the way Homer did, where the freedom of action of the hero, Achilles, was greater than our own, and instead of viewing war as realistic, as Stendhal did in The Charterhouse of Parma or Tolstoy did in War and Peace, with Fabrizio or Pierre exercising the same confusion and freedom of action we, the readers have, Great War writers did something else. They told us of the ironic nature of war, how it is always worse than we think it will be, and how it traps the soldierno longer the heroin a field of force of overwhelming violence, a place where his freedom of action is less than ours, where death is arbitrary and everywhere. What had happened in 191418, Fussell argued, happened again in later wars, whose narrators built on the painful achievement of the soldier writers of the Great War. Men like Owen, Sassoon, Rosenberg, Gurney were thus sentinels, standing in a long line of men in uniform who were victims of war just as surely as the men they killed and the men who died by their side.

Paul Fussell had his ironic moment during the Battle of the Bulge, which no one had anticipated in its ferocity and daring. When the German thrust began and the shells hit, he was with a sergeant who had taught him how to be an officer and how to take seriously his responsibility for the young soldiers under his command. He owed everything to that sergeant. Until the day I die, he said when we met in Germany, I will tell anyone who wants to hear how much I owed him. The two men hit the ground during the bombardment, and in a moment or two, only one of them stood up. Fussell dedicated

Next page